Horsekeeping (12 page)

Authors: Roxanne Bok

Heading to the barn, we spotted Bobbi, already tanned, sun-bleached blonder and comfortably poised atop a green John Deere front loader, picking up fallen limbs from the grassy entrance. She looked in her element, all smiles as usual. We talked some basic business about recent demolition progress and turned to the eviction of the few remaining mares and the once-celebrated stallion stud Stanislav.

“They should all be gone by the end of the week,” Bobbi reported, proud that she had placed the four Arabians. “But I'm not sure about that one mare.”

We looked toward the near paddock at the segregated skinny bay considering a drink from the black plastic bucket at her feet. She looked fine, like the rest, lazy from years of inattention. But as we gazed, on cue to Bobbi's words, the mare changed her aspect. She raised her head slightly, looking perplexed for a fraction of a second. She shuddered, twice, like she had caught a sudden chill, before sinking sideways over buckled legs to the ground. The collapse had the appearance of a staged faint, a too-tightly-bound, airless Victorian, sighing and lilting gracefully to the ground. The horse's head landed last, and even before she became completely still, up she scrambled, clumsily. She shook herself and again grew vaguely confused, like she could not remember having lain down, no easy effort for a horse.

“She's been falling down all week, just like that I suppose, though until now I've only witnessed her getting back up. Dr. Kay took some blood, but it must be a neurological problem, almost like epilepsy, because she rights herself and carries on like nothing happened.”

The mare wandered away to a better patch of grass and grazed, seeming to accept her condition without anxiety.

Animals don't seem to worry

, I thought.

Animals don't seem to worry

, I thought.

“She's awfully thin,” I pointed out.

“Well, she's getting her share of the feed but can't keep weight on. She's not the low horse on the totem pole eitherâthat fat mare is, believe it or not. Sometimes a sick horse is pushed out of the way and not allowed to eat, but she gets right in there.”

“Can she be helped?”

“We'll try.” Bobbi wrinkled her nose. “But I'm afraid we might have to euthanize her.”

Sapped of carefree optimism, I fast forwarded to how much harder this will be when it is one of our own adored and long-cared-for pets.

This one didn't even have a name. Death is bad enough, but it is the preceding suffering, particularly by animals, that deeply disturbs me.

This one didn't even have a name. Death is bad enough, but it is the preceding suffering, particularly by animals, that deeply disturbs me.

“The sooner the better, I suppose,” I said quietly.

“We're just waiting for the test results to make sure there isn't anything we can do,” Bobbi replied.

“Just don't tell Jane or Elliot,” Scott said protectively.

Don't tell me,

I thought.

I thought.

“Or Roxanne,” Scott added, as if he heard my brain whispering.

“What do you do with the body?” I imagined a large vehicle with straps and hoists. “Does the vet take it away like with dogs and cats?”

Bobbi winced. “No, you just dig a hole.”

Our eyes rested once more on the mare's ribbed sides. I inwardly willed her to not convulse again. We moved on to happier topics before Bobbi climbed back aboard her tractor, and Scott and I continued our walk, along the road this time. It was our first brush with mortality at our new farm and probably not the last. The predicted cloud-cover overtook the confident blue of the sky. I pulled my coat collar close around my neck against the chill and leaned into Scott. Silently developing thicker skins, we bent our forms into the rising wind, toward lively, healthy children and the comfort of home.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Into the Woods

W

E TOOK THE PLUNGE: we owned a horse farm. Endless work, lots of money, sickness and death thrown inâhow did we get into this mess, overburdened with needy acres, decrepit buildings, ailing and dependent animals?

E TOOK THE PLUNGE: we owned a horse farm. Endless work, lots of money, sickness and death thrown inâhow did we get into this mess, overburdened with needy acres, decrepit buildings, ailing and dependent animals?

For Scott, I knew this peculiar destiny related to the landâbut how? Occasionally I nosed around Scott's past to uncover the seedling of his affinity for rural New England, but came up fallow. Nature poetry is not his cup of tea: he's more of a history and politics buff than a romanticist or a fictionalist. While I escape into Emerson and Thoreau and the Berkshire writers, he thrives in the competitive maze of Wall Street wrestling other capitalists. He is a poster boy for the great American story. Having immersed his youthful self in countless biographies of accomplished men from sports stars to steel magnates, from the age of twelve he planned to head east for school and a career in business. He worked hard at university, endured unglamorous summer jobs, and made two risky but ultimately brilliant career decisions: first, to leave corporate law for investment banking way back in the mid-eighties before the field became so popular and, second, to leave a ten-year, secure position at a prosperous large bank for a start-up boutique.

Scott was the fourth partner to join; eight years later there were forty-plus in a global operation listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Luck played its part as it does in many a bootstraps story: in his case the right

place and time of being a white, educated, ambitious male born in the United States. He made the most of his opportunities, success met him halfway, and, at least from my perhaps protected perspective, he made the hard slog look relatively easy. I marvel at his skill and efficiency, and the security he has provided for our family, especially since money and I seem to part company as congenital fact. Making and hanging on to money is a talent like any other; Scott possesses it, I do not.

place and time of being a white, educated, ambitious male born in the United States. He made the most of his opportunities, success met him halfway, and, at least from my perhaps protected perspective, he made the hard slog look relatively easy. I marvel at his skill and efficiency, and the security he has provided for our family, especially since money and I seem to part company as congenital fact. Making and hanging on to money is a talent like any other; Scott possesses it, I do not.

Scott had a Midwest suburban childhood, an urban college experience, a Jersey girl wife, a Wall Street job, a Big Apple life: yet, as soon as we paid off our loans and could afford it, he and I took to the country like spring salamanders to vernal pools. I know as a kid my husband spent hours catching frogs (and shooting them with a BB gun, he admitted) in the wetlands near his house, but he never revealed much nostalgia for his younger years in Michigan. His father took him deer hunting once, but Scott sat in the woods and read

The Grapes of Wrath

âin its entirety. No kills. But that is all I uncovered from my husband's veiled past: a foggy window to his nascent nature soul.

The Grapes of Wrath

âin its entirety. No kills. But that is all I uncovered from my husband's veiled past: a foggy window to his nascent nature soul.

I hailed from the “Garden State,” not the bucolically equine western part of the state, but the strip-malled, smelly, oil-drenched northeast and southern shore. As a kid, I remember regularly burying my nose into my grandmother's sweater on certain stretches of the New Jersey Turnpike and watching the stacks of the Budweiser factory pour smoke across the endless squat, laddered refinery tanks beyond. I recognized the landmarks in

The Sopranos

series' opening credits and knew people who could slip into those story lines with ease. According to my husband, I am an “animal nut,” but my inclination is toward smallish, easily managed, clean, non-drooling, non-shedding, heavily-domesticated varieties. And Scott and I are not “handy,” as individuals or as a couple. We bicker while simply hanging pictures. Our “suburbanity” and urbanity had not afforded us any traction in the wise and practical rusticity of the country. Even our six-year-old daughter admonished: “Dada, you don't look like the tractor type.”

The Sopranos

series' opening credits and knew people who could slip into those story lines with ease. According to my husband, I am an “animal nut,” but my inclination is toward smallish, easily managed, clean, non-drooling, non-shedding, heavily-domesticated varieties. And Scott and I are not “handy,” as individuals or as a couple. We bicker while simply hanging pictures. Our “suburbanity” and urbanity had not afforded us any traction in the wise and practical rusticity of the country. Even our six-year-old daughter admonished: “Dada, you don't look like the tractor type.”

In our young married life we never thought we would even stay in this country, let alone settle in stodgy New England. Restless Anglophiles with the youthful spirit of exploration, one year after we purchased our first house in Salisbury, we knocked the dirt of the US of A from our shoes and moved to London for five years, from 1990â1995. Scott accepted a posting there, and we left with few thoughts of returning. Arriving on August 1st, the hottest day recorded in British history to that date, I panicked at the realization that air-conditioning did not exist in either houses or cars. Not comfortable outside the parameters of a 68â75 Fahrenheit degree window, I was all for flying home, pronto. All too soon I understood: we strode coolly damp and dimly lit through the next five years of British weather.

We enjoyed much travel, taking full advantage of a childless existence (fourteen married years) and the short plane rides to the Continent, but we never really fit in with the British and remained outsiders despite our officially stamped passports designating us permanent residents. I missed skyscrapers and food delivery, NYC street life and even rude, impatient salespeople, the twenty-four hour never-close pace, blue skies and white puffy clouds on frigid winter days, the blare of sunshine, the wilting summers, American enthusiasm and

naiveté

, a fat slice of greasy-good pizza, and the relaxed atmosphere of friends

eating out

rather than

dining in

at formal dinner parties planned weeks in advance. I hear London now sports a more American casualness, but I regret this slide toward globalization. My pet peeves largely made England, England, like antiquated paternalistic BBC telly and gun-less Bobbies on bicycles with nightsticks. Many of them carry guns now, and it saddens me.

naiveté

, a fat slice of greasy-good pizza, and the relaxed atmosphere of friends

eating out

rather than

dining in

at formal dinner parties planned weeks in advance. I hear London now sports a more American casualness, but I regret this slide toward globalization. My pet peeves largely made England, England, like antiquated paternalistic BBC telly and gun-less Bobbies on bicycles with nightsticks. Many of them carry guns now, and it saddens me.

I think Scott could have been happy in London indefinitely, but I chafed at a rootless exile, despite my happy years of literary study there. We left five years to the day we arrived, significantly changed and with England a part of us still. We made some good friends, mostly expatriates with lives similarly colored. My first-born's arrival six weeks before the move home meant we would not go back to American life as we knew

it five years earlier: clever of us because return can be so disappointing. But that London cured our restlessness became the best souvenir of our sojourn; we found home. If I had not lived abroad, I would have gone to my grave yearning for greener pastures. I now believe in New York and Connecticut with solid confidenceânot with defensive my-place-is-better-than-your-place bombast, but with steadfast, personal confidence of knowing my own heart's desires. It is not for everyone, but I chose the teeming, exhausting, nerve-wracking, frustrating, glorious New York City, tempered by the Puritan rocky soil and artistic pastoral beauty of New England, and never looked back.

it five years earlier: clever of us because return can be so disappointing. But that London cured our restlessness became the best souvenir of our sojourn; we found home. If I had not lived abroad, I would have gone to my grave yearning for greener pastures. I now believe in New York and Connecticut with solid confidenceânot with defensive my-place-is-better-than-your-place bombast, but with steadfast, personal confidence of knowing my own heart's desires. It is not for everyone, but I chose the teeming, exhausting, nerve-wracking, frustrating, glorious New York City, tempered by the Puritan rocky soil and artistic pastoral beauty of New England, and never looked back.

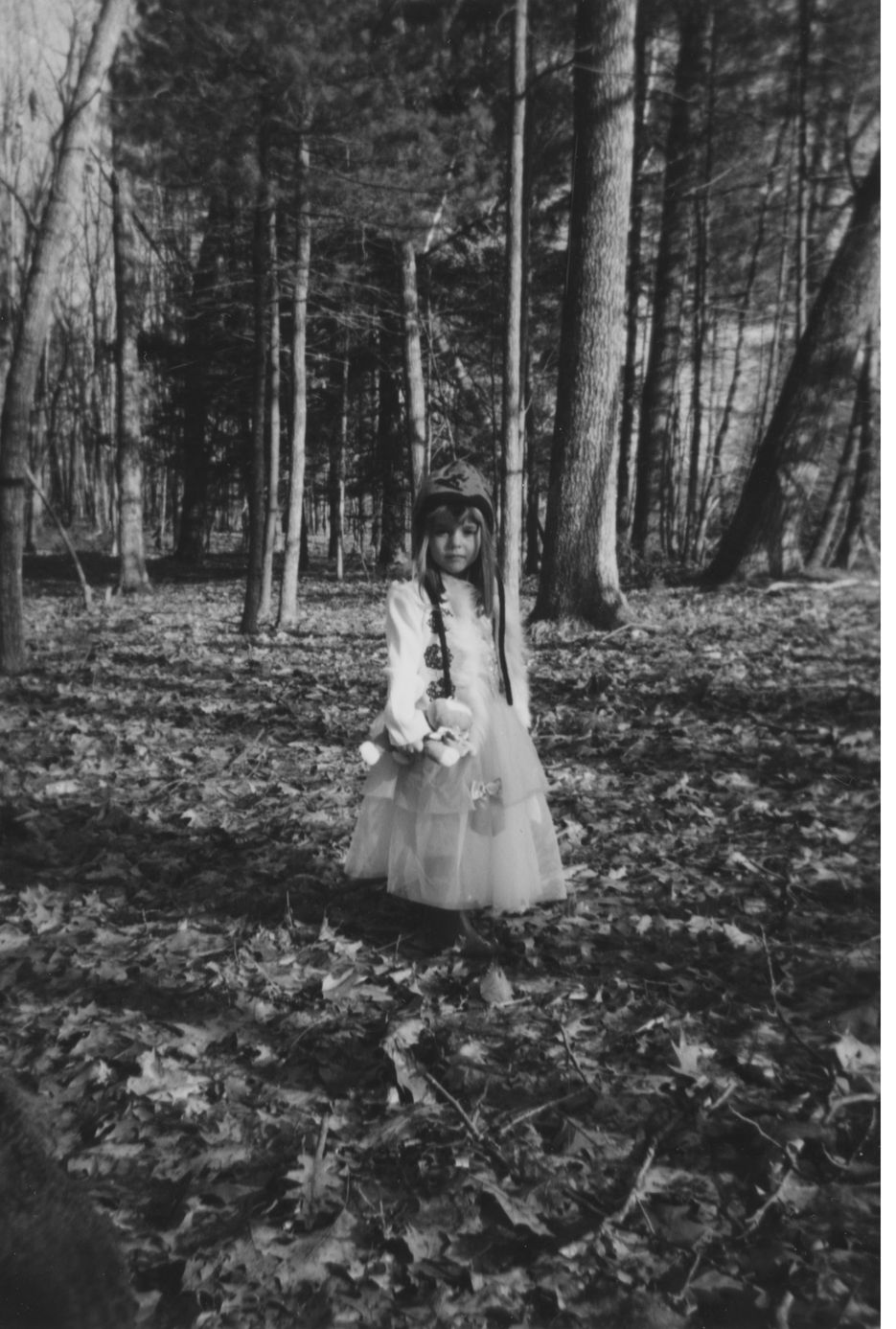

Over the years we have dug into our repatriated territory with a vengeance. Our English sabbatical conditioned us to appreciate the Connecticut countryside: the weekend jaunts to Wales and rural England, the green, green, green misty valleys, the sheep-dotted hillsides, the walking trails encouraging trespass across private property, the ancient stone walls and hedgerows, the rustic pub convenient to refresh the wet, weary foot soldier. For Scott, this might have been the sum total of what turned him into a country boy and thus steered us toward Weatogue Stables. But for me, England's demure countryside was only a refresher course. When we returned to Connecticut, I embedded in the American forests because they invoked a past I had carefully vaulted. Sure, this Yankee terrain was breathtakingly beautiful. Yet underlying that, I fell in love with “the woods” because they reminded me of long ago people, places and times gone by. Repairing to our tree-insulated, rural home was to dip into my personal warehouse of memory and experienceâan amplification of childhood beauty and wonder seared by the melancholy of loss and the hard-earned lessons of growing up.

Â

Â

I WAS A NORMAL KID, strong-willed and pushing at boundaries as unapologetic preadolescents do. Then just as I turned nine, my mother, Marilynne Marie, died.

I learned something that June day in 1968âbad things can happen to anyone, anytime, right out of the blue. I spent the next forty years waiting for the other shoe to drop, anticipating the next horrible thing about to happen; expecting the worst. The twisted goal, I suppose, was to cheat surprises and worry fate into submission. A “dyed in the wool pessimist” my husband insists, but I say I'm a fact-facer. I am also in a hurry: fully informed that life can be short, especially when beautiful, it is best to hit the ground running to get through all you can before your calamity finds you.

Other books

1492: The Year Our World Began by Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

The Debriefing by Robert Littell

CHOSEN: A Paranormal, Sci-Fi, Dystopian Novel by A. Bernette

A Second Chance at love The Rocker Girls Series by Jennifer Byars

Sally James by Fortune at Stake

Night Sky (Satan's Sinners MC Book 3) by Kay, Colbie

Chronicles of Eden - Act 2 by Alexander Gordon

Reckless Fear (The Black Vipers #1) by Micki Fredricks

Too Grand for Words (BookStrand Publishing Romance) by Natasza Waters

The Rat Patrol 3 - The Trojan Tank Affair by David King