Horsekeeping (42 page)

Authors: Roxanne Bok

We turned onto the wide path that Meghan had mown through the high fields, the hay already ripe for the season's first harvest. Winding through two fields and woods, around the seventy or so acres, we enjoyed the undulations of green-to-golden grass in the sweeping breezes. Birds took wing out of the meadows, swooping to stitch crazy patterns of blue sky and white clouds. Bandi and Angel relaxed on an outing that didn't require concentration or ring-defined circling. Angel's swift walk prompted lazy Bandi and me to trot occasionally to catch up. I chatted loudly to Bobbi, my method to flush any more birds or camouflaged deer and turkeys well before we got to them, but even the bugs respected our peace.

I appreciated this ride as “one of life's wonderful moments” moment: out on my own trusty steed (well, sort of trusty), in a preserved field, on a farm approaching its beautiful apotheosis after more than a year of renovation and impatient questioning,

will it ever be done

? The dirt piles but a memory, all lumpy overgrown paddocks had been leveled off and were re-growing in various stages of baby grass, their tender blades peeking through the hay we laid to protect the seed. Ferns were feathering their tendrils and the trees, young and ancient, were popping open to full-domed shade umbrellas. My attuned senses absorbed every last detail of spring with almost paranormal awareness. Was green ever so verdant, the light ever so lucid? I floated, a light-hearted butterfly able on the breeze. The distant barn stretched long and proud, its fresh paint

daring the wear and tear of a new chapter. Though we gratefully intuited Mrs. Johnson's venerable experiences etched within the old grains of these barns and the furrows of these paddocks and fields, our history on this patch of land was yet to unfold; I rode poised between El-Arabia's past and Weatogue Stables' future.

What stories await us? What adventures?

will it ever be done

? The dirt piles but a memory, all lumpy overgrown paddocks had been leveled off and were re-growing in various stages of baby grass, their tender blades peeking through the hay we laid to protect the seed. Ferns were feathering their tendrils and the trees, young and ancient, were popping open to full-domed shade umbrellas. My attuned senses absorbed every last detail of spring with almost paranormal awareness. Was green ever so verdant, the light ever so lucid? I floated, a light-hearted butterfly able on the breeze. The distant barn stretched long and proud, its fresh paint

daring the wear and tear of a new chapter. Though we gratefully intuited Mrs. Johnson's venerable experiences etched within the old grains of these barns and the furrows of these paddocks and fields, our history on this patch of land was yet to unfold; I rode poised between El-Arabia's past and Weatogue Stables' future.

What stories await us? What adventures?

Loud neighing roused me from my reverie. In addition to Chase, we had recently welcomed two new horses who were playing in their paddocks: OneZi, a four-year-old gelding training under saddle and his sire, Royaal Z, a sleek, twenty-two-year-old black stallion. They both belonged to Sabrina, a keen equestrienne from distant Greenwich, who sacrificed proximity for full day turn-out and a large paddock over which her “boys” could hold dominion. Three more boarders were due. In the early days, Scott, Bobbi and I concluded “if we build it they will come,” and they have: lovely people and horses. With Weatogue Stables off to a fine start, I rode the land deeply moved by this rare, storybook experience. It is worth the fear, the falls, the hassle, the time management, the child worry, the spousal friction.

We rounded the bend and slow-poked home. Without warning and in an instant Angel leaped right and Bandi, in unison as if they were of one mind and body, did the same only higher and farther. A beady-eyed turkey head had popped up out of the tall grass inches from Angel's feet and skittered noisily into the woods stage left. Bobbi and I both held on, and the horses quickly settled upon reassurance of hysterical fowl rather than that dreaded equinevour. Bobbi had mentioned earlier that Meghan sometimes encouraged Bandi to chase the wild turkeys from his paddock.

“Oh great, Meghan,” I teased. “Just what I needâa horse that races after turkeys.”

But Bandi didn't pursue the panicked bird, and I quietly noted that each time Bandi spooked I settled just a bit sooner. During my first Bandi trail ride last summer, I awaited the worst, panic my only mode.

Over time I still worried, but also inched toward acceptance of inevitable “challenges” out in the big bad world of unforeseen circumstances; and, as in life off the trail, sometimes you stay on, and sometimes you fall off. I counted my blessings that I stuck this time, and Bobbi and I congratulated one another. It goes against my nature to look on the bright side, but I did, and the psychology worked . . . some.

Over time I still worried, but also inched toward acceptance of inevitable “challenges” out in the big bad world of unforeseen circumstances; and, as in life off the trail, sometimes you stay on, and sometimes you fall off. I counted my blessings that I stuck this time, and Bobbi and I congratulated one another. It goes against my nature to look on the bright side, but I did, and the psychology worked . . . some.

That night, drifting into sleep, I jumped awake in my bed, as we sometimes do when dreaming of falling. But this was a leap, exactly the sensation of Bandi spooking, and it happened three times before I finally trusted slumber. I shook off my inclination to label it a bad omen.

CHAPTER TWENTY

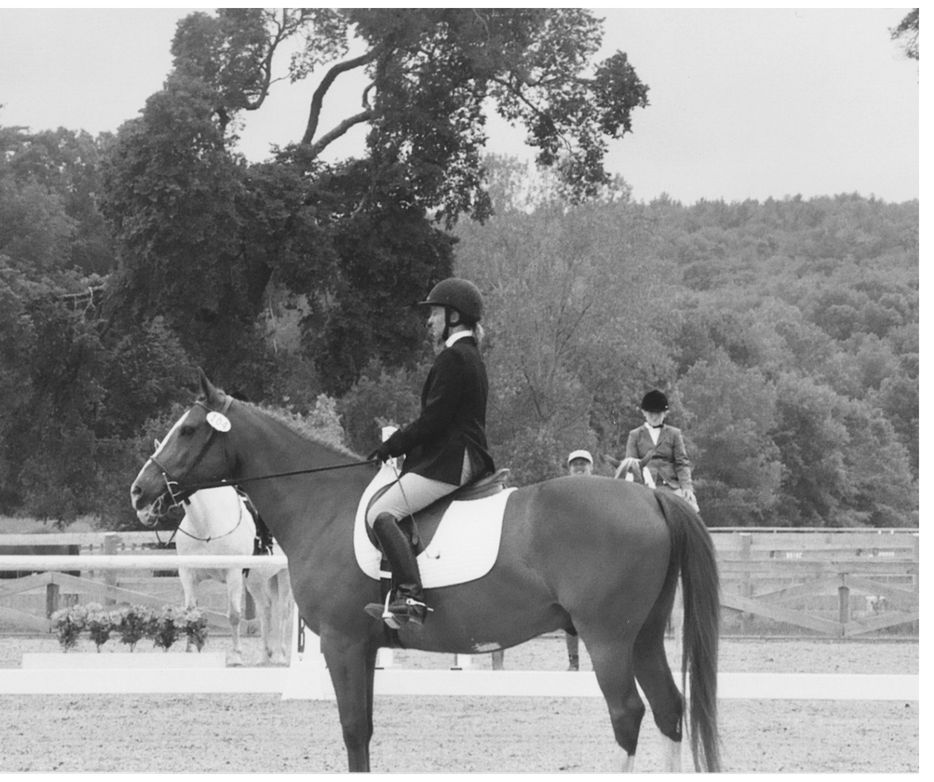

Our First Show

W

EATOGUE'S INAUGURAL BIANNUAL DRESSAGE EVENT would take place the Sunday of the June weekend that the kids and I migrated to Salisbury for eleven weeks of summer vacation. Weekdays at the farm and no commuting on Friday and Sunday nightsâwhat bliss. At least for three of us: Scott's work held him to the city, but he aimed for a few weeks off in July and August. It had been increasingly hard to leave on Sunday nights: the farm had morphed into our own Emerald Isle, its viridescence softening any memory of mud, machinery and workmen. It was time to revel in its glory.

EATOGUE'S INAUGURAL BIANNUAL DRESSAGE EVENT would take place the Sunday of the June weekend that the kids and I migrated to Salisbury for eleven weeks of summer vacation. Weekdays at the farm and no commuting on Friday and Sunday nightsâwhat bliss. At least for three of us: Scott's work held him to the city, but he aimed for a few weeks off in July and August. It had been increasingly hard to leave on Sunday nights: the farm had morphed into our own Emerald Isle, its viridescence softening any memory of mud, machinery and workmen. It was time to revel in its glory.

Arriving late Friday night, we had little time to prepare for the event. Elliot and I had been practicing our tests the last few weekends, and enough riders had signed on that Bobbi split the Intro categories into adults and juniors. Elliot regretted that he and I wouldn't compete head on, but not meâI didn't want to win, and I didn't want to lose, either. I work hard to improve my kids' skills only to feel geriatric when they eventually best me at everything one by oneâchess, throwing and hitting a baseball, swimming, running, skiing, math, riding, life.

Salisbury had already weathered ten days of rain and flooding. Sunday's forecast predicted a washout, but horse events take place rain (barring lightning) or shine. Saturday, practice day, dawned overcast. Since Bobbi was frantic setting out flowers, aligning the dressage rings and gussying up the barn for company, I soloed on Bandi. While last year I took my maiden fall the day before my first show, this time I rode my test with relative ease. A hard-earned accomplishment: I could tack up, take a ride and untack

sans

babysitter. I knew that Bobbi, Meghan and Brandy kept one eyeball on me most of the time, but they hid it well. Elliot seemed ready too, and though showing wasn't a priority, he is a born grade-grubber keen to obtain a score on which to improve, measuring himself against himself. Generally competitive with his peers, against type he inclined to keep this aspect of his life strictly personal pleasure.

sans

babysitter. I knew that Bobbi, Meghan and Brandy kept one eyeball on me most of the time, but they hid it well. Elliot seemed ready too, and though showing wasn't a priority, he is a born grade-grubber keen to obtain a score on which to improve, measuring himself against himself. Generally competitive with his peers, against type he inclined to keep this aspect of his life strictly personal pleasure.

We were rider-ready and the farm was show-perfectânearly. Despite assurances, Mike let us down: our raw fences stood unpainted though May boasted perfectly dry days. But so much had changed, transformation enough to satisfy even Scott. This time last year the grounds were patched with small lakes and islands of muck, and though Scott and I glared at the dirt piles excavator Kenny shifted around for months on end, we now believed. Our farm drained like the Mohave. We completed the barn by topping the rooftop cupola with a bespoke weathervane of a dressage horse, in full stride with gold-gilded tail and mane above the banner “Weatogue Stables,” gleaming in not-yet weathered bronze. Operatic birds repatriated the renewed gazebo, and were relieving themselves with impunity on the flagstones and my new benches, tables and chairs. It does resemble an aviary, and no doubt they pegged us the intruders.

At our house a robin couple nested in the topiary outside the front door. Established before our summer pattern had us banging in and out all day every day, these surprised birds nevertheless stuck it out, keeping their four blue eggs warm. The children and I kept watch to see three of the eggs reveal the sparsely fuzzed, loose-limbed hatchlings. The indolent fourth took two more days to break out. We marveled at their metamorphoses. Over ten days, their naked cowering slid into feathery battles for space and food until, unable to stand their siblings and the close quarters any longer, they departed the nest, one by one. Our

housekeeper Lourdes was especially excited. In the Filipino culture, hosting baby birds brings great fortune.

housekeeper Lourdes was especially excited. In the Filipino culture, hosting baby birds brings great fortune.

“It's good luck, Mum. Lots of money coming,” she said, smiling and rubbing her fingers together.

She said the same thing about the ant swarm that engulfed our patio one day, and then, just as mysteriously, disappeared.

“Look kids: ant world,” I said.

“Cool,” said Elliot.

“Wow,” said Jane.

“

More

money, Mum,” said Lourdes, palms rubbing.

More

money, Mum,” said Lourdes, palms rubbing.

I designated these events signs of a prosperous farm, my definition being a break even on operating costs. We lost track of the renovation expenses, not really wanting to know the grand total and having never aspired to recoup these or the purchase price. Some figures are best kept hazy. Almost to confirm my new found stock in Filipino mysticism, another robin, or maybe the same one, reused the nest and reproduced the identical family unit of four eggs, again with three hatching together and the last two days later. Scott rescued one fallen baby successfully, and Lourdes shook her amazed head at the numerous portents predicting our coming windfall.

But deep down I knew that few can coax the economics of a horse business out of the red, no matter how much work, hope and love you expend, or how you fudge the numbers. With the onslaught of bills for everything from horseshoes to light bulbs, I fully understood how Mrs. Johnson's “successful ” Arabian breeding farm eluded her in the end. Horses beat up everything. We had already replaced fence boards rubbed, pushed and snapped by horses with itchy butts, gates that crafty horse lips unhinged, metal stall guards that robust chests bent and cracked, countless metal latches and chains demolished by muscular bodies and dexterous teeth, and though I vociferously explained to the offenders that they cannot, absolutely can not chew on the carpentry of their stall windows and doors, they would lift their handsome

heads from their labors, look at me with soulful eyes, whinny apologies as I backed away with my pointer wagging, then immediately resumeâgnaw, gnaw, gnaw. Fact: a barn is only a heartbeat away from dirty, broken and bankrupt; it takes deep pockets by the owners and constant vigilance by the manager and stable hands to keep it together.

heads from their labors, look at me with soulful eyes, whinny apologies as I backed away with my pointer wagging, then immediately resumeâgnaw, gnaw, gnaw. Fact: a barn is only a heartbeat away from dirty, broken and bankrupt; it takes deep pockets by the owners and constant vigilance by the manager and stable hands to keep it together.

I still hadn't met Weatogue's former owner. Mrs. Johnson had undergone surgery for a brain tumor, and I had hoped her recuperation would allow her to attend our show. I wanted to tell her how much we liked the farm and how well it worked, how right the bones were set and how thoughtfully she had laid the blueprint, how excited we were, how her legacy of horses on this land would continue. I wanted to right my earlier, rash judgment of her now that I personally experienced the challenges of horsekeeping. Yet, I awaited a serendipitous introduction and shied from knocking on this private woman's door, or even writing her a letter. Would she see our renovations as crudely excessive, a recrimination? Was El-Arabia's transformation painful to her or a relief?

“I think she's happy and sad,” Bobbi said. “It's hard to let go sometimes.”

I suspect Bobbi was shielding me from Janet's verdict on our interpretation of her farm, sensing correctly that the guilt would eat at me: now that I so valued Weatogue Stables' reincarnation, I cared what this horsewoman thought. But this farm was traveling a course that, by necessity, relegated El-Arabia's history to deeper layers of the land under its footprint.

I would regret my hesitation: Mrs. Johnson died ten days before our event. A small service with no calling hours marked her passing. She willed her house to MIT, grateful to the educators who had empowered her to finance her passion for breeding Arabians. In the tack rooms we hung two pictured plaques, mementoes she had presented to Bobbi about the heyday of El-Arabia and her best stallion, Gwasz. I thought of her often when out on the trail gazing at the barns and her house beyond.

A nurse shared Janet Johnson's last moments: with eyes closed she laid on her bed with a full view of the farm. As she could no longer see,

the nurse described the farm activity: Meghan, Brandi and Bobbi leading the horses, hips swaying, tails twitching and heads bobbing from the fields into the barn for their dinner in the soft glimmer of a lowering sun. A lone whinny; the rhythm of hooves; a human admonishing a horse to mind his manners; feed and water buckets banging; spring renewing. A tear trailed Janet's cheek. Perhaps she was revisiting her own beloved Arabians, her singular favorites, shushing their hungry neighs and impatient kicks. Maybe she was looking into their crinkle-lidded eyes, kissing their velvet muzzles, one hand smoothing a polished neck and the other reaching deep into her crumb-lined pocket for a last biscuit. I imagined she grieved at the possibility of a horseless future, but perhaps the spirits of her husband and horses of old escorted her comfortably on. I hoped she found some satisfaction in another's equine dream that would live on in the beauty of well-kept horses experiencing optimal lives in fields and woods on a rescued New England farm reliably fecund with impending summer.

the nurse described the farm activity: Meghan, Brandi and Bobbi leading the horses, hips swaying, tails twitching and heads bobbing from the fields into the barn for their dinner in the soft glimmer of a lowering sun. A lone whinny; the rhythm of hooves; a human admonishing a horse to mind his manners; feed and water buckets banging; spring renewing. A tear trailed Janet's cheek. Perhaps she was revisiting her own beloved Arabians, her singular favorites, shushing their hungry neighs and impatient kicks. Maybe she was looking into their crinkle-lidded eyes, kissing their velvet muzzles, one hand smoothing a polished neck and the other reaching deep into her crumb-lined pocket for a last biscuit. I imagined she grieved at the possibility of a horseless future, but perhaps the spirits of her husband and horses of old escorted her comfortably on. I hoped she found some satisfaction in another's equine dream that would live on in the beauty of well-kept horses experiencing optimal lives in fields and woods on a rescued New England farm reliably fecund with impending summer.

Other books

El Círculo de Jericó by César Mallorquí

To Win Her Love by Mackenzie Crowne

The Lucky Years: How to Thrive in the Brave New World of Health by David B. Agus

When Passion Flares (The Dark Horse Trilogy Book 2) by Dane, Cynthia

Empower by Jessica Shirvington

Blood Kin by MARIA LIMA

The Field of the Cloth of Gold by Magnus Mills

In the Land of Milk and Honey by Jane Jensen

Savage Sacrifice: Savage Angels MC #5 by Kathleen Kelly

The Gardens of Democracy: A New American Story of Citizenship, the Economy, and the Role of Government by Eric Liu, Nick Hanauer