House of Hits: The Story of Houston's Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios (Brad and Michele Moore Roots Music) (12 page)

Authors: Roger Wood Andy Bradley

Tags: #0292719191, #University of Texas Press

By the way, as writer Rich Kienzle makes clear in his liner notes essay for

The Essential George Jones,

“the song broke George out of obscurity, though not totally the way he (or Starday) would have liked.” As sometimes happened in those days, this surprise hit by a newcomer was quickly seized upon, rerecorded, and rushed to release by someone else. In this case, “Red Sovine and Webb Pierce, both established stars, covered the song as a duet for Decca Records. Given their star status, their version became the Number 1 record.”

Nevertheless, “Why Baby Why” signaled the arrival of Jones, and he subsequently recorded several other singles at the Gold Star facility engineered by Quinn. The biggest seller came in 1956 with the Jones-penned song “Just One More” (#264), peaking at number three. Among the others were “What Am I Worth” (#216, which went to number seven), “Ragged But Right,” “Seasons of the Heart,” “You Gotta Be My Baby” (#247), and a duet with Jeanette Hicks entitled “Yearning” (#279). At least two of those original Starday recordings were later released also on Mercury: “Just One More” (#71049) and

“Yearning” (#71061). Moreover, a few other songs, such as “Don’t Stop the Music” (#71029), were recorded at Gold Star and issued only on Mercury.

Jones and Daily thereafter staged sessions in Nashville. As an artist-producer team, they continued to collaborate through 1971, creating many other hit recordings. Supposedly it was the singer’s 1969 marriage to Tammy Wynette that eventually led Jones away from Daily, for within a year Jones was making records with her producer, Billy Sherrill. Nevertheless, Daily and Jones had experienced a productive partnership for fi fteen years, and they likely had a fairly close personal relationship. Sleepy LaBeef, a fellow musician, says: Pappy was great to all of us, but his main deal, you know, was “Thumper”

[Jones]. Yeah, well back then he like adopted George and treated him almost like he was his son, you know. George always came fi rst with Pappy. The rest of us had to line up, but George was quite a talent, and he still is. We all knew that George was the main man. Just like in Memphis, Carl Perkins and the others knew that Elvis was the main man there.

p a p py d a i ly a n d s t a r d ay r e c o r d s

4 7

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 47

1/26/10 1:12:12 PM

Jones, who has continued performing and recording in the twenty-fi rst century, is now generally acknowledged (despite some highly publicized personal foibles) as one of the greatest singers in country music history. But back when nobody could have predicted that he would ever achieve that rarefi ed cultural status, he began establishing himself during those Gold Star sessions.

Perhaps Daily’s nurturing had something to do with that. Jones had found his own distinctive voice, and he had let it sing with a naturally fl owing intensity of spirit. Though his style was still infl uenced by that of his idol Hank Williams, he was no longer merely imitating but creating something new.

However, sometimes a sequence of seemingly random circumstances can unexpectedly coalesce into a life-changing experience. Such was the case with the momentous recording session that yielded “Why Baby Why,” as the memories of several studio insiders reveal.

In

his

New Kommotion

interview, fellow Starday recording artist Eddie Noack explains the situation that led to the then-rare phenomenon of the featured singer double-voicing the song all by himself.

George Jones wasn’t selling anything on Starday to begin with. So they were cutting George [singing] with Sonny Burns to help him—stuff like

“Heartbroken Me” [#165] and “What’s Wrong [with] You” [#188]. And they were going to do a third one, and this was the biggest break George ever had

[because] Sonny liked to drink, and he didn’t show up for a Burns/Jones session, and you know, it was “Why Baby Why.” Because Sonny did not turn up, George had to cut it on his own, and he overdubbed his own voice over it.

Thus, whether fans realized it or not, they were hearing the Jones voice har-monizing with itself on the catchy chorus of the song. Given that it was 1955, this technique was unusual, requiring some studio innovation.

Generally speaking, the technology that enables a singer to record a second vocal track, while wearing a pair of headphones and listening to prerecorded tracks of both the instrumentation and his own lead vocal, did not become common until the 1960s. To enable Jones to sing the background vocal part with himself on “Why Baby Why,” Quinn would have had to set up a small speaker in the studio. He could then play the track back to Jones at a very low volume while the singer added his second vocalization. Meanwhile, Quinn could then record the original track plus the more recently performed second vocalization to a second tape recorder. Because the editing technology of “punch-ins” (or “drop-ins”) was not yet established, Jones would have had to do all of his second vocal parts in a straight run-through of the song—after he and the band had already performed the complete song live in the studio as fl awlessly as possible. Given the double-voicing eff ect achieved on “Why

4 8

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 48

1/26/10 1:12:12 PM

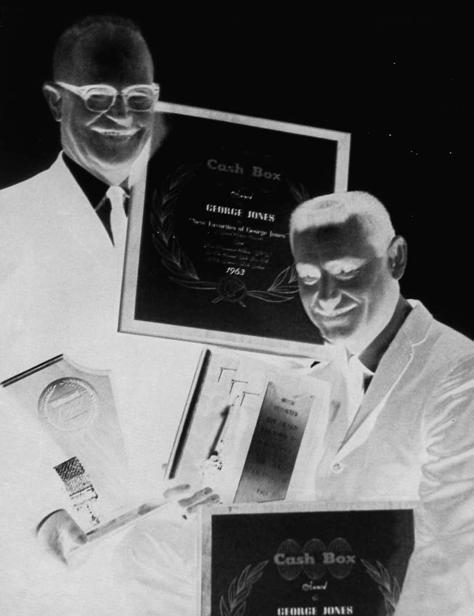

Pappy Daily and George Jones,

publicity photo, 1963

Baby Why,” its fi nished sound depended not only on Jones’s fl awless singing with himself but also on innovative studio engineering by Quinn.

Glenn Barber, a regular Gold Star house musician at the time, off ers other details about the session that yielded this breakthrough record: One recording I remember was “Why Baby Why” by George Jones. When we did that session my little boy was in diapers, and my wife had him on her lap and was patting him on his butt to keep him quiet because there was no-p a p py d a i ly a n d s t a r d ay r e c o r d s

4 9

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 49

1/26/10 1:12:12 PM

where to sit except in the studio itself. Herbie [Remington] was on steel and Tony Sepolio on fi ddle. Doc Lewis played piano. . . . I also played on “Seasons of My Heart” [by Jones], and it was the same band as “Why Baby Why.” We pretty much always had the same band on these sessions.

Despite the ultimate success of those fi rst Jones recording sessions in Houston, musician Tony Sepolio reveals that it did not come easily. In an interview published by Andrew Brown in

Taking Off ,

Sepolio recalls his role in and exasperated impressions of trying to collaborate with Jones:

“Why Baby Why.” I got the band for him. He called me. It took him all day to make it. I’m not used to that. . . . Man, it took him all day to make the darn thing. He’d get drunk. . . . He went through a fi fth of whiskey. He’d say, “Wait a minute, I forgot the chords,” stop right in the middle of it. We’d start again, and then he’d say. “Ah, that’s not the words.” And I mean, I was up to here with him. Because when I was with [Jerry] Irby [bandleader of the Texas Ranchers], we’d make ’em boom-boom-boom. In one day, we made fi ve 15-minute radio programs [transcriptions]. We might miss a note here or word there—we didn’t care; we’d just keep going. And [on the “Why Baby Why” session] here’s this idiot, man. Toward the end he’d say, “I forgot the words.” We took a break about lunchtime. And [Jones] was going through his fi fth of whiskey. And I told Lew [Frisby, bass player], “Hey, if we can’t whip him, let’s join him.” So we went down to the corner and got us a six-pack of beer.

I got frustrated with him. I swore that I’d never record with him again—

and I never have. I told Jones, “Man, don’t ever call me again.” We got paid union wages, but it wasn’t worth it.

As such testimony makes clear, even in the early days, a Jones recording session could be a challenge for all involved. Steel guitar player Frank Juricek has his own recollections. “I remember a George session that took all night, 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., and we got only two songs done,” he claims.

Yet, even in the midst of such proceedings, the Gold Star Studios founder Quinn tended to maintain his composure and eventually get the desired results. Consider this anecdote from musician Glenn Barber:

Bill was a great guy with a good sense of humor. I remember one early session with George Jones that wasn’t going so well because he’d been drinking a bit too much. Bill fi nally came out and had a conference with all of us. He said, “Do you boys think we can do this on the next take?”

We all said, “Sure, we can do it.”

5 0

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 50

1/26/10 1:12:12 PM

George said, “I can sing it perfect. Let’s do it and get out of here.”

Bill said, “I don’t want to put any pressure on you, but I only have one acetate dub left.” So we cut it.

Building on Quinn’s ability to achieve successful resolution of in-studio diffi

culties, Jones recorded several more tracks at Gold Star even after he had made the jump from Starday to Mercury Records. At least two of those tracks became 1957 hits: “Don’t Stop the Music” (#71029) crested on the

Billboard

country charts at number ten, and “Too Much Water” (#71096) climbed as high as number thirteen.

It was not until Daily moved Jones’s sessions to Nashville and made the 1959 Mercury recording of “White Lightning” (#71406), which rose all the way to number one on the charts, that the initial success of “Why Baby Why” and

“Just One More” was surpassed. Although several takes on “White Lightning”

(written by J. P. Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper) had previously been recorded at Gold Star, the later hit version was a product of the Nashville studio scene (including the presence of Hargus “Pig” Robbins on piano).

All in all, Jones released at least twenty-seven songs that were recorded at Gold Star Studios in the mid-1950s. (It is possible that other Jones songs were recorded there but never released, or they may have appeared without session credits on one or more of his early albums.) Though he would eventually become a legendary Nashville fi gure, this country singer from Beaumont launched his bid for stardom close to home in Houston. Accordingly, he—

like the studio where he made “Why Baby Why”—is a key part of Texas music history.

rockabilly delivered a powerful jolt to much of the country music recording industry in the mid-1950s. Young white artists such as Bill Haley, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis—borrowing heavily from the African American–formed genre of electric blues—were speaking a new kind of musical language, one that drew simultaneously from country and early R&B.

Across the nation, multitudes of white teens and young adults passionately liked what they heard and soon redefi ned, often to the angst of the older generation, popular tastes and standards for commercial success. By February of 1956, when Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” became a number one hit, many country music producers were scurrying to react to this major shift in public opinion. Consider this anecdote from Starday rockabilly hit-maker Rudy Grayzell, as told to writer Dan Davidson: “I remember poor ol’ Hank Locklin, man. We’d all moved on to rock ’n’ roll, and on one show we did, he got up and did his straight country thing, and the kids let him have it with hotdogs and paper cups!”

p a p py d a i ly a n d s t a r d ay r e c o r d s

5 1

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 51

1/26/10 1:12:12 PM

But Daily had perhaps seen this change coming, and he had already recorded several rock ’n’ roll and rockabilly sides prior to Elvis’s ascension in pop culture. Among the earliest Starday records in that vein were Sonny Fisher’s “Rockin’ Daddy” (#179) and “Hey Mama” (#190) and Sonny Burns’s

“A Real Cool Cat” (#209).

The swell of commercial interest in this fast-paced style of new music even prompted Daily and Jones to return to Gold Star Studios in early 1956 specifi -

cally to record rockabilly. The results included a cover version of “Heartbreak Hotel” and a pair of original songs by Jones: “Rock It” and “How Come It.”

In May the last two titles were released as alternate sides of a Starday single (#240) under the rockabilly-inspired pseudonym Thumper Jones. Public response to this record was indiff erent, prompting the producer-artist duo to focus thereafter solely on straight country music.

Yet by no means did Daily quit recording rockabilly. He just shifted his focus to more suitable artists on the Starday roster. Moreover, he would expand that emphasis even more, within a couple of years, on his many Gold Star productions for D Records.

One of the most noteworthy Starday artists in the rockabilly genre was Rudy “Tutti” (Jimenez) Grayzell (b. 1933), a native of Saspamco, near San Antonio, Texas. Unlike many of his Starday peers, Grayzell did not make his fi rst records at Gold Star Studios, for he had already cut his three singles for Abbott Records (where he sang in a traditional country style) back in 1953.

While those records did not generate many sales, they were good enough to earn Grayzell guest appearances on both the

Grand Ole Opry

and the

Louisiana

Hayride

radio programs. Grayzell, who was honing a more progressive rockabilly-tinged sound, then signed with Capitol Records, which released three more singles (under the pseudonym Rudy Gray), but scored no hits.