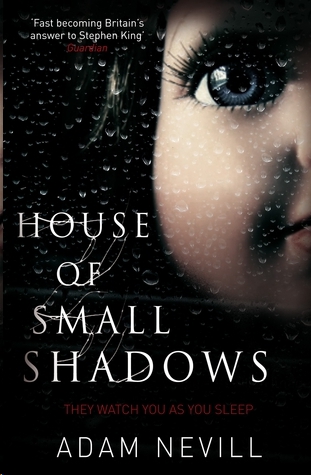

House of Small Shadows

For James Marriott

1972–2012

The first editor who brought me into print as a novelist, a faithful reader of my first drafts, a fellow devotee of the weird, and a great friend for fifteen years. Who will I

rearrange the dark furniture of my mind with now? You are sorely missed, my friend, and always will be.

By a merging and interplay of identities between himself and his beautiful room, he might be preparing a ghost for the future; it had not occurred to him

that there might

have been a similar merging and coalescence in the past

.

Oliver Onions

The Beckoning Fair One

As if by a dream Catherine came to the Red House. She abandoned her car once the lane’s dusty surface was choked by the hedgerows, and moved on foot through a tunnel of

hawthorn and hazel trees to glimpse the steep pitch of the roof, the ruddy brick chimneys and the finials upon its sharp spine.

Unseasonably warm air for autumn drifted from the surrounding meadows to settle like fragrant gas upon the baked ground beneath her feet. Drowsy and barely aware of the hum emitted from the

yellow wildflowers and waist-high summer grasses so hectic in the fields, she felt nostalgic for a time she wasn’t even sure was part of her own experience, and imagined she was passing into

another age.

When she came across the garden’s brick walls of English bond, seized by ivy right along their length to the black gate, a surge of romantic feelings so surprised her, she felt dizzy.

Until the house fully revealed itself and demanded all of her attention.

Her first impression was of a building enraged at being disturbed, rearing up at the sight of her between the gate posts. Twin chimney breasts, one per wing, mimicked arms flung upwards to claw

the air. Roofs scaled in Welsh slate and spiked with iron crests at their peaks bristled like hackles.

All of the lines of the building pointed to the heavens. Two steep gables and the arch of every window beseeched the sky, as though the great house was a small cathedral indignant at its exile

in rural Herefordshire. And despite over a century of rustication among uncultivated fields, the colour of its Accrington brick remained an angry red.

But on closer inspection, had the many windows been an assortment of eyes, from the tall rectangular portals of the first three storeys to the narrower dormer windows of the attic, the

house’s face now issued the impression of looking past her.

Unaware of Catherine, the many eyes beheld something else that only they could see, above and behind her. Around the windows, where the masonry was styled with polychromatic stone lintels, an

expression of attentiveness to something in the distance had been created. A thing even more awe-inspiring than the building itself. Something the eyes of the house had gazed upon for a long time

and feared too. So maybe what she perceived as wrathful silence in the countenance of the Red House was actually terror.

This was no indigenous building either. Few local materials had been used in its construction. The house had been built by someone very rich, able to import outside materials and a professional

architect to create a vision in stone, probably modelled on a place they had once admired on the continent, perhaps in Flemish Belgium. Almost certainly the building was part of the Gothic revival

in Queen Victoria’s long reign.

Judging by the distance of the Red House to the local village, Magbar Wood, two miles away and separated by hills and a rare spree of meadowland, she guessed the estate once belonged to a major

landowner advantaged by the later enclosure acts. A man bent on isolation.

She had driven through Magbar Wood to reach the Red House, and now wondered if the squat terraced houses of the village were once occupied by the tenants of whoever built this unusual house. But

the fact that the village had not expanded to the borders of the Red House’s grounds, and the surrounding fields remained untended, was unusual. On her travels to valuations and auctions at

country residences, she hardly ever saw genuine meadows any more. Magbar Wood boasted at least two square miles of wild land circling itself and the house like a vast moat.

What was more difficult to accept was that she was not already aware of the building. She felt like an experienced walker stumbling across a new mountain in the Lake District. The house was such

a unique spectacle there should have been signage to guide sightseers’ visits to the house, or at least proper public access.

Catherine considered the surface beneath her feet. Not even a road, just a lane of clay and broken stone. It seemed the Red House and the Mason family had not wanted to be found.

The grounds had also known better days. Beneath the Red House’s facade the front garden had once been landscaped, but was now given over to nettles, rye grasses and the spiky flowers of

the meadow, thickets trapped half in the shadow of the house and the garden walls.

She hurried to the porch, when a group of plump black flies formed a persistent orbit around her, and tried to settle upon her exposed hands and wrists. But soon stopped and sucked in her

breath. When no more than halfway down what was left of the front path, a face appeared at one of the cross windows of the first storey, pressed against the glass in the bottom corner, left of the

vertical mullion. A small hand either waved at her or prepared to tap the glass. Either that or the figure was holding the horizontal transom to pull itself higher.

She considered returning the wave but the figure was gone before she managed to move her arm.

Catherine wasn’t aware there were any children living here. According to her instructions there was only Edith Mason, M. H. Mason’s sole surviving heir, and the housekeeper who would

receive Catherine. But the little face, and briefly waving hand, must have belonged to a pale child in some kind of hat.

She couldn’t say whether it had been a girl or a boy, but what she had seen of the face in her peripheral vision had been wide with a grin of excitement, as if the child had been pleased

to see her wading through the weeds of the front garden.

Half expecting to hear the thud of little feet descending the stairs inside the house, as the child raced to the front door to greet her, Catherine looked harder at the empty window and then at

the front doors. But nothing stirred again behind the dark glass and no one came down to meet her.

She continued to the porch, one that should have stood before a church, not a domestic house, until the sombre roof of aged oak arched over her like a large hood.

One of the great front doors crafted from six panels, four hardwood and the top two filled with stained glass, was open, as if daring her to come inside without invitation. And through the gap

she saw an unlit reception, a place made of burgundy walls and shadow, like a gullet, that seemed to reach into for ever.

Catherine looked back at the wild lawns and imagined the hawkbit and spotted orchids all turning their little bobbing heads in panic to stare at her, to send out small cries of warning. She

pushed her sunglasses up and into her hair and briefly thought of returning to her car.

‘That lane you have walked was here long before this house was built.’ The brittle voice came from deep inside the building. A woman’s voice that softened, as if to speak to

itself, and Catherine thought she heard, ‘No one knew what would come down it.’

ONE WEEK EARLIER

All of the small faces were turned to the door of the room. A myriad glass eyes watched her enter.

‘Jesus Christ.’

The number of dolls and even their intentional arrangement startled Catherine less than the sense of anticipation she felt in their presence. She briefly imagined they had been waiting in the

darkness for her like guests at a surprise party for a child, a century before.

Even if she were the only living thing in the room, she remained as still as the dolls and returned their glassy stares. If anything moved, she would let go of the shriek that had built like a

sneeze.

But after a moment of immobility she realized she was staring at the most valuable hoard of antique toys she had seen in her years as a valuer, in her time as a producer of television shows

about antiques, and even as trainee curator at a children’s museum.

‘Hello? Hello, Mr Dore. It’s Catherine. Catherine Howard.’

No one answered. She wanted someone to. Having had to let herself into the room was awkward enough.

‘Sir? Hello, it’s Catherine from Osberne, the auctioneers.’ She stepped further inside. ‘Hello?’ she repeated quietly enough to have given up on anyone being

present.

The bathroom door was open, the cramped yellowy space beyond it unoccupied. Unused clothes hangers chimed inside an empty wardrobe. Walnut, but badly scratched. Some yellowing stationery and a

poor male attempt at hospitality refreshments crowded one side of the little desk.

The living area of the room appeared unused by anyone besides the dolls. Many of which were arranged on the undisturbed quilt, a handmade eiderdown on a brass-framed bedstead as old as the

building. Upon the wall at the head of the bed was a framed woodcut of a small square church set within neat grounds.

The only other item that appeared to belong to the legal guardian of the collection was a trunk. Between the bed and the window a large leather chest had been placed. Upon the lid of the trunk

sat another row of dolls. Their little legs hung over the edge of the aged and watermarked leather. A backdrop of fussy, not entirely white, net curtain before the solitary window smothered the

afternoon’s grey light and formed a fitting background to the little figures, as if they were trapped inside an old photograph.

Even the upholstered chair that partnered the desk was occupied by a doll. And that figure was the most magnificent of them all.

Catherine didn’t close the door in case Mr Dore returned, the Mason family’s legal representative, and the solicitor instructed to discuss an auction of their ‘antique

assets’ with her. The letter from Edith Mason mentioned nothing else.

She guessed Mr Dore might have popped out and been delayed getting back to the appointment, though she hadn’t seen a pub in Green Willow, nor had she spotted any building in the village

offering the prospect of communal activity, let alone food. Even finding Green Willow had been a struggle. Beside the Flintshire Guest House, the village was little more than a line of stone

buildings, a closed post office and a weed-filled bus stop. No cars were parked outside any of the cottages.

Catherine checked her watch again. The thin old man downstairs, in the tiny alcove serving as a reception, had definitely said, ‘Go right up.’ When he handed her keys, he’d not

even removed his eyes from whatever he’d been reading behind the counter.

The proprietor issued the impression he was accustomed to, if not worn down by, hordes of visitors to what was a small establishment, barely on the English side of the border between

Monmouthshire and Herefordshire. Accustomed to elderly locals being curious about her visits to remote places, Catherine had paused before the tiny counter to say, ‘Mr Dore is up

there?’ The man in reception did not answer, but snuffled with irritation and twitched his threadbare head over his book.

‘I’ll just go right up then.’

Meeting a prospective client in a hotel room was also a first but, in her brief though rapidly growing experience as the valuer for Leonard Osberne, she’d found that eccentrics and

descendants of eccentrics from Shropshire to Herefordshire, the Welsh border, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, who used the firm to auction the contents of homes and attics long sealed from the

modern world, were becoming less unusual. Leonard had a broad range of oddballs on his books. She was beginning to think he didn’t have anything else.