House of Steel: The Honorverse Companion (69 page)

Read House of Steel: The Honorverse Companion Online

Authors: David Weber

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Fiction, #Space Opera, #Action & Adventure, #General

By the time the Star Kingdom of Manticore and the People’s Republic of Haven actually met in combat, both sides had been actively preparing for over half a T-century. In theory, the level of readiness—both for the fleet and for its “shore establishment”—was very high on both sides. Indeed, the peacetime ammunition loadout for the Royal Manticoran Navy was identical to its wartime loadout, and from 1880 PD on, personnel strengths aboard Manticoran warships were maintained at one hundred percent of wartime manning requirements. The People’s Navy was at a lower level of manning, and although it was theoretically at the same level in terms of matériel, it was, in fact, probably at no more than eighty-five percent of Manticoran levels of readiness prior to about 1904 PD. At that point, in the Legislaturalists’ deliberate buildup to hostilities against Manticore, readiness was increased to very nearly the same level as in the RMN. One effect of the increase in personnel, however, was to dilute the experience levels of its units on the very verge of war by the introduction of so many newly trained personnel. This was exacerbated by the PRH’s educational deficiencies, since it took a proportionately longer time for Havenite personnel to acquire the necessary expertise.

The Star Kingdom of Manticore, however, had a significant advantage in terms of its fixed-support infrastructure. It had fewer fully developed bases and depots, but those it possessed were much more capable and tended to be considerably larger. They were maintained at that level by a rigorous system of training exercises, drills, and inspections intended to ensure (largely successfully) that when the inevitable hostilities against the People’s Republic of Haven began, the fleet’s support structure would be as close to one hundred percent readiness as was humanly possible. In terms of mobile logistical support, there was no real comparison between the two navies. The RMN’s organic logistical command was far more highly developed and capable, and the sheer size of the Manticoran merchant marine gave the Admiralty a far deeper pool of “ships taken up from trade” which could be used to augment the Navy’s own personnel and supply lift at need.

ACQUISITION STRATEGY

Finally, there’s the question of how you go about buying the stuff you need for your navy, especially given that a warship is a significant capital investment with a long design cycle and construction cycle.

The Royal Manticoran Navy’s acquisition strategy and requirements were greatly eased by the size and capability of the Star Kingdom of Manticore’s industrial base. The fact that the Star Kingdom’s home industries built and maintained one of—if not the—largest merchant fleets in the entire galaxy gave it a basic “heavy industry” capability no other single star system could have matched. The possession of the Manticoran Wormhole Junction, coupled with the size of the Manticoran merchant marine, provided a cash flow for the Manticoran government of prodigious size. Even a minor increase in Junction transit fees generated a major increase in revenues, and Manticore was in a position to leverage its status as a major financial and investment center into the sale of war bonds and other investment instruments to support its war effort. Despite that, and even with unprecedented levels of taxation, the Star Kingdom was forced into a pattern of deficit spending that was distinctly alien to its traditional fiscal policies. This resulted in a significant level of inflation for the first time in modern Manticoran experience, although by the standards of most wartime economies, Manticore’s managed to avoid “overheating” through a combination of wise fiscal management, the continuing expansion of its merchant fleet and carrying trade, aggressive pursuit of still more foreign markets for civilian goods as a means of maintaining and expanding its general industrial base and economy, and the enormous “natural resource” provided by the Junction.

As the war continued and emphasis shifted more and more drastically toward missile combat with the introduction of the multidrive missile, platform costs came to be dominated by ammunition costs, and enormous missile production lines were set up. Strenuous efforts were made at every stage in the process to rationalize weapons design in a way that would permit the most economical possible volume production. Given the sheer scale of that production, the per-unit cost of not simply expendable munitions but of warship hulls and components fell drastically as the war continued. Despite the much greater size and lethality of the MDM, the cost of a late-generation multidrive missile was actually lower for the Star Kingdom than the cost of a late prewar single-drive missile had been, largely because of the relatively small numbers in which those prewar weapons had been purchased and manufactured and because the “bells and whistles” of their design had not been nearly so ruthlessly rationalized. One of the outstanding achievements of the Star Kingdom’s military industrial base throughout the Havenite Wars was the ability to introduce new and even radically upgraded weapons without major disruptions of output, largely as a legacy of Roger III’s insistence on prewar planning towards exactly that end.

In contrast, the People’s Republic was never able to match the efficiency of Manticoran industry and ship building, nor did it have a resource remotely like the Manticoran Wormhole Junction as a revenue generator. It did, however, have a command economy that was over a century old when the war began. In many ways, the PRH was less constrained by fiscal policy than Manticore because its domestic economy was a largely closed system which the government could manipulate in whatever fashion it chose. Ultimately, the strain was ruinous and unsustainable, but in the short- and midterm, the government was in a position to direct and control resources and trained manpower in a way Manticore simply couldn’t have matched. The coercive power of State Security and the other revolutionary police and spy organizations set up under Oscar Saint-Just at Robert Pierre’s direction also helped enormously in providing “direction” to the Havenite war effort. And, last but not least, the sheer numbers of political prisoners held by the PRH provided Haven with a massive supply of slave labor which required no wages whatsoever.

Under the circumstances, Pierre’s ability to actually reform the PRH’s currency, rationalize taxation, reduce the Basic Living Stipend, and reintroduce the notion of wage-based labor was little less than miraculous. It would never have been possible without the iron support of StateSec and of the People’s Commissioners assigned to the PRH’s military forces and it was accompanied by a degree of disruption and civilian hardship which required often brutal measures (see the Leveller Revolt in 1911 PD), but that should not be allowed to take away from the sheer magnitude of the accomplishment.

Despite that, it is questionable how much longer Pierre or Saint-Just could have sustained the PRH’s war effort if the introduction of the MDM in 1914 PD had not brought the first phase of the Havenite wars to a crashing halt. It is indisputably true that the Star Kingdom proved far more capable than Haven of transitioning back to a peacetime economy in the wake of Thomas Theisman’s overthrow of the Committee of Public Safety, and the ongoing economic strain of the Havenite civil war between Theisman’s supporters and those still loyal to the Committee of Public Safety or seeking to carve out their own empires came very near to undoing Pierre’s accomplishments. The sheer size of the PRH came to the restored Republic’s rescue, however, proving once again that with a sufficiently large population and resource base, even a relatively inefficient economy can generate large absolute revenue streams.

Putting It All Together

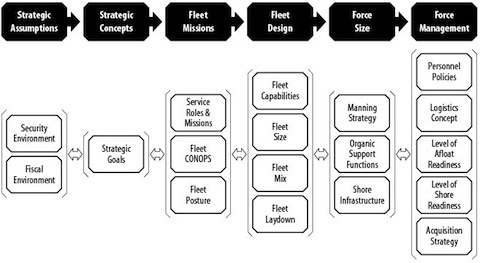

The model we have described is shown in the figure below.

These, then, are the sorts of things one needs to think about when designing a navy. The answers to each of these questions do not exist in a vacuum—not only do earlier decisions set the stage for later decisions, but there is a lot of interrelatedness between the issues under discussion. Those feedback loops have been omitted from the illustration for sake of clarity, but they are there.

Sometimes it might become apparent later in the process that an earlier decision has created an untenable situation downstream. In the real world, this mismatch is an indication that the process needs to be rethought, usually because the original plan was too ambitious. An author has a bit more leeway, and can change “ground truth” to provide the answers he needs for narrative purposes.

This model comes from the “Naval Metaphors in Science Fiction” talk that Chris often does at science fiction conventions. He observes that most science fiction does not cover the whole model; at best it might cover Fleet Missions and Fleet Design in detail, with most other areas only vaguely defined. It would be disingenuous to say that David went through each and every one of these steps as presented when he defined the navies of the Honorverse. But, one thing Chris noted when he showed David the illustration above was that David had a ready answer for each and every one of these sections, answers that were obviously the result of long and careful analysis of both real-world history and the setting he had created. In the real world, these are questions that must be answered. In a fictional universe, an author at least needs to know these questions exist, and to have thought about them, even if only in general terms.

The view presented here is obviously not the final word on the topic, as each and every one of these subheadings could be an essay in and of itself, for each navy in the Honorverse. In addition, there are a lot of elements that we’ve only glossed over. First, there are a lot of important issues below that are not discussed, such as the political will to build a navy. Second, a navy is a dynamic thing—it changes with time. Sometimes this is because technology changes, but oftentimes it is because other factors change: The strategic situation gets better or worse; new missions get added, old missions get subtracted; the education level of the population changes, affecting the navy’s personnel requirements, etc. Science fiction authors have the luxury of a clean sheet of paper, but real policymakers do not, and sometimes tomorrow’s navy is defined not by the navy they want but by the navy they have today. Third, this model does not discuss the importance of doctrine and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TT&P). Doctrine describes what you want to do, and TT&P describes how you use your stuff to do it, so generally doctrine is an important input into the design process, and TT&P is an important output. (For our purposes, you can think of doctrine and tactics as being part of the fleet you are buying.) Finally, the entire process is permeated by a discussion of the potential threat. Threat is part of the strategic environment, it determines the usefulness of individual ship design, it affects basing and force sizing decisions, etc.

In other words, there’s plenty more ideas to explore!

Frequently Asked Questions

David Weber

What are the other sentient species and how do they interact with humanity?

I regret to say that we aren’t going to answer this question in any detail at this time. I will say that there are additional sentient species in the Honorverse, at least one of whom has been “uplifted” to current human levels of technology and trades with humans. I have taken the position in the Honorverse, however, that it is unlikely for there to be numerous species at comparable or near comparable levels of technological development at any given moment. And, since I chose to write about a human-versus-human conflict, humanity had to be the primary star-traveling species. By default, that moved most of the nonhuman species to pre-space and/or primitive technologies. The reason I’m not going to answer this question in detail is that while I have several species roughed out, I don’t intend to introduce them into the books anytime soon, and as a storyteller, I need to keep my options open on reworking or modifying my rough notes in order to best suit my needs at the time I do introduce them. Assuming, of course, that I do!

Where is Amos Parnell as of 1921 PD? What is he doing and, most important, what does he think of the resurrected Republic of Haven?

Amos Parnell is still living in exile in the Solarian League. He is in something of an ambiguous position, given his prewar rank in the People’s Navy and his status as one of the few surviving members of a truly prominent Legislaturalist family. He is on very friendly terms with the new, restored Republic’s government, but Eloise Pritchart is just as happy to have him safely out of the domestic political mix, for several reasons. The biggest one is that despite the restoration of the Republic, people hankering for the “glory days” of the conquering People’s Republic of Haven still exist, although they are an enormously marginalized fringe at the present time. She has no desire to bring home Legislaturalist émigrés who might, willingly or otherwise, serve as a rallying point for the lunatic fringe. On the flip side, Parnell is the most visible, most senior surviving member of the Old Regime of the Legislaturalists. If he were to return home, his life would be in permanent danger at the hands of people who still have grudges, very well deserved grudges, in many instances, against the Legislaturalists. He sees the resurrected Republic as his birth star nation’s last and best chance at redeeming its soul, and having seen the corruption of the Legislaturalists from inside the belly of the beast and having experienced the brutality of the Committee of Public Safety firsthand, he is a strong and powerful supporter of the effort to restore the pre-PRH Republic. At the moment, however, his best opportunity for doing that (and surviving in the process) is to speak for it from abroad.

What are the larger political entities outside the Solarian League and how large are they?

There aren’t very many “larger political entities” outside the Solarian League, the Andermani Empire, and the Republic of Haven. Remember that even though the People’s Republic of Haven had only a teeny tiny number of member star systems compared to the League, it was the largest extra-Solarian political unit. After the League, the Silesian Confederacy was closest to the PRH in terms of inhabited star systems, but calling the Confederacy a star nation would have been too generous by the seventeenth century post diaspora. It had already become a failed state at that point. The truth is that the Manticoran Wormhole Junction had an enormous amount to do with the emergence of the Republic of Haven, its transformation into the People’s Republic of Haven, and its eventual restoration. Although it was called the “Haven Sector,” that was more an example of Solarian arrogance hanging a label that suited its perceptions on the region. The true focal point of the quadrant’s interaction with humanity in general was the Junction, which gave access to the region directly from Beowulf at the very heart of the Solarian League. However, the Star Kingdom of Manticore was a kingdom, a monarchy, and it was an article of faith in the League that monarchies (which were not members of the enlightened Solarian League, at any rate) were automatically primitive neo-barbarians, which is one reason they have appended that label to Manticore so persistently. The fact that Manticore is fabulously wealthy and refuses to kowtow to the League only strengthens that Solarian attitude towards the Star Empire . . . especially now that it has become, in very truth, an empire. Haven, on the other hand, had a robust, capitalist economy, was busily expanding and exporting its citizenry and its institutions to other star systems in the vicinity, and was a republic. As such, it was far more acceptable to the League and

ipso facto

became the “dominant power” of the quadrant even before the PRH turned conquistador.

It was, however, actually the access available through the Junction which drew outside wealth, migrating populations, and ever-increasing and ever-denser trade to the “Haven Sector,” with the result that outside the heart of the Solarian League itself, that region became the wealthiest and most densely settled one. And out of that density of population, that concentration of wealth, and that attractive effect on additional wealth and people, emerged the multi-system star nations in the vicinity. It may be best to think of the Haven Sector as an outlying lobe of human expansion that leapfrogged over the intervening space courtesy of the Junction. The Verge, the sort of surrounding crater ringwall of independent star systems between the League’s member systems and the Haven Sector, consists almost exclusively of single-system star nations, with here or there two or three star systems which may have leagued together into a minor local power. It is the absence of local power blocs which could be considered true star nations which makes the Verge so vulnerable to the Office of Frontier Security’s steady encroachment. The fact that the Star Empire of Manticore is creating such a local power bloc in the Talbott Quadrant, thereby preventing an option to ingestion by OFS or its minions, explains another layer of the Solarian League’s hostility towards Manticore.

There were several modest-sized star nations within two or three light-centuries of Sol in the first couple of centuries after the creation of the Solarian League prior to about 1400 PD. In the roughly 125 to 150 T-years following the development of the impeller drive and the Warshawski sail, however, the League expanded to incorporate those star nations into its membership. Aside from a handful of mini-Leagues (in the sense of economic unions) like the Rembrandt Association, however, there are very few true multi-system star nations outside the League. That is not to say that there aren’t other relatively wealthy single-system star nations (like Erewhon) or entities which would like to be star nations but which haven’t been allowed to coalesce because of OFS’ policies (like Smoking Frog), simply that there aren’t any larger political entities, which was what the question asked about.

Before the Republic of Haven became the PRH and embarked upon the Duquesne Plan of conquest, what was the tone of relationships between the RoH and the SKM?

Prior to the emergence of the People’s Republic of Haven, the Star Kingdom’s relations with Haven were actually very good. While it was the Junction which accommodated so much of the population movement into the Haven Sector, Haven was actually settled around a century before the Star Kingdom, thanks to the emergence of the impeller drive and Warshawski sail, which allowed the initial Haven colony expedition to overtake and pass the sublight Manticore colony ship

Jason

. It was a well-financed expedition, the quadrant contained a higher than average concentration of desirable star types, it established a vigorous economy and an attractive political system, and it aggressively and actively sought to bolster and support follow-on waves of settlers. As a consequence, it was seen as the “Athens of the Verge” by many, including the Star Kingdom of Manticore. Manticore had never had the population Haven did and, prior to the discovery of the Junction, was essentially an out-of-the-way star system which didn’t go out of its way to draw attention to itself or (after the Plague Years, at least) actively seek to promote immigration. By the time the Junction was discovered, Manticore had become accustomed to thinking of Haven as the “way of the future,” and it took some centuries for the Star Kingdom to begin to recognize the true nature of the commanding economic and strategic advantage the Junction conferred upon it. There was no Manticoran merchant marine, really, before the Junction was surveyed in the 1580s, and by 1650, the Republic had begun its slide into the People’s Republic, although that didn’t become readily apparent to the outside galaxy for quite some time and immigration into the Republic actually increased rather dramatically once the Junction gave access to Beowulf. During that seventy-year window, the Star Kingdom became an ever more potent economic force, building its merchant marine and coming to decisively dominate the carrying trade of the Haven Sector (including the transport of quite a few of those Haven-bound immigrants). What was not immediately apparent to either Manticore or Haven was that in the process, the Star Kingdom was replacing the Republic as the region’s dominating economic power.

Throughout the period prior to 1750 (that is, for a period of very nearly two hundred T-years following the discovery of the Junction) Manticore and Haven traded with one another, joined with Beowulf in endorsing the Cherwell Convention, cooperated in piracy suppression and the suppression of the slave trade, and were, in fact, the two poles of the economic engine of the Haven Sector. However, the truth was that the Star Kingdom could be, and would have been, a major economic power even if the Republic of Haven had never existed, given the existence of the Junction. Following the Havenite Economic Bill of Rights in 1680, a gradual cooling of the relationship set in. By the time Haven promulgated the Technical Conservation Act in 1778, the once close relations between Haven and Manticore had largely disappeared. The growing resentment of Manticoran prosperity among Havenites, and especially among the growing Dolist class, as the Republic’s economy stalled and then began to contract, only made that situation worse. The new Constitution of 1790 was the frosting on the cake as far as Manticoran admiration of Haven was concerned, and by the time the Duquesne Plan was formulated, the People’s Republic already recognized that its greatest potential stumbling block would be the Star Kingdom.

If the revolution hadn’t happened, is it fair to say that the Peeps would have had a very good chance of beating the Manticore Alliance?

I don’t think I’d go so far as to say that the Peeps would have had a “very good” chance of beating the Manticoran Alliance. I will say that they probably would have had at least an even chance of victory if the Revolution, the Committee of Public Safety, and the Pierre purge of the Legislaturalists (and, of necessity, the officer corps) hadn’t intervened. Their fleet was bigger, they actually had more experience in combat operations than the RMN, and their economy, although much less efficient, was much larger than Manticore’s. In order to win, however, they really would have had to overpower the Star Kingdom in the first rush, the way they had all of their earlier victims. With time for Manticore to absorb the shock of the initial attack and fully mobilize its economic and industrial power, the numerical odds were bound to begin to equalize, because unlike Manticore, the PRH had very little “slack” in its economy and industrial sector. In effect, Haven was already running at wartime production levels, whereas Manticore was still running essentially at peacetime production levels, with significant capacity for increasing its output. Moreover, the R&D programs which had been put in place by Roger III in the forty years or so leading up to his assassination had unbalanced the playing field more than anyone (including Manticore) realized at the time. It would have come down to a question of whether or not the PRH would have been able/willing to pay the cost in very high casualties to overwhelm the SKM’s already developed and deployed qualitative superiority before the even greater qualitative superiority inherent in Manticore’s R&D came into play. By the standards of the later period of the Havenite Wars, the casualties involved probably would have been no more than moderate, but no one knew that in 1905, and I would say that it’s probably unlikely the Legislaturalists would have risked the scale of losses involved, once they realized what that scale was, because of the implications it would have had for the internal stability and security of the PRH. In many ways, Pierre’s successful coup, which owed a great deal to the PN’s initial losses, was simply a demonstration of what probably would have happened at some point fairly early in a protracted war between the Legislaturalist regime and the Star Kingdom if the PRH had decided to wage a war of attrition against the SKM’s superior weapons systems, 1905-style.

To what extent are planets in the Honorverse dependent upon food import from other planets?

That depends entirely on the planets in question.

Grayson

was something of an extreme case of a planet finding it difficult to feed its own population because of environmental circumstances, but for all intents and purposes, the orbital farms could be said to be a sort of surrogate for food imported from other planets. There are other worlds which for various combinations of reasons have found it more economically advantageous to import food in substantial quantities rather than producing it locally. The relative cheapness of interstellar transportation in the Honorverse is such that it is viable to rely on out-system sources of food, but most planets get nervous if their total food supply depends on imports. It is much more common for imported food to consist of luxury items or staples which happen not to do very well in their local ecosystem. Beef from Montana, for example, commands a very good price on the import market. There are also planets whose populations have simply grown to a level at which supplementary food sources from out-system are necessary to sustain a comfortable nutrition level. Old Earth falls into that category, at least at the present time, because the inhabitants of Old Earth have chosen not to produce food in the quantities needed to sustain their diet from internal sources. Partly that’s because the planetary population is so large, partly it’s because land values are so high that people can always find a “better use” for it than as cropland, and partly it’s because imported food supplies are simply cheap enough that it would be extraordinarily difficult to compete with them pricewise given land costs, material costs, and wage costs on Old Earth. That doesn’t mean the planet couldn’t produce enough food on its own surface to feed its population; it simply means it hasn’t chosen to produce food in those quantities. As a very rough analogy, it costs less to truck commercial quantities of lettuce in from Florida than it does to grow it in roof gardens in Manhattan.