Hover Car Racer

Authors: Matthew Reilly

MATTHEW REILLY

PART I: JASON AND THE ARGONAUT

‘Imagine twenty fighter jets racing around a twisting turning aerial track, ducking and weaving and overtaking at insanely high speeds and you’ve just imagined a hover car race.’

- Rand Thomasson

3-time Hover Car Racing Champion

INDO-PACIFIC REGIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS,

GULF OF CARPENTARIA, AUSTRALIA

The race was barely nine minutes old when Jason Chaser lost his steering rudder.

At 690 kilometres an hour.

The worst thing was, it wasn’t even his fault. Some crazy kid from North Korea driving a home-made hunk-of-junk swamp-runner had lost control of his car while trying to pull an impossible 9-G turn and had crashed spectacularly into the crocodile-infested marshes right in front of Jason, sending sizzling pieces of his car flying in every direction - three of which punched

right through

Jason’s tailfin like a volley of red-hot mini-meteorites, rendering his steering vanes useless.

Jason jammed back on his collective, and somehow managed to right the

Argonaut

with only his pedal-thrusters just as -

shoom!-shoom!-shoom!

- three of the other top contenders whizzed by, rocketing off into the distance, kicking up geyser sprays in their wakes. The

Argonaut

slowed to a complete stop, hovering three feet above one of the thousands of water-alleys in the vast swamp at the edge of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The Bug’s voice came in through Jason’s earpiece. The Bug was Jason’s navigator, co-driver and little brother. He sat in the back of the

Argonaut

‘s cockpit, slightly above and behind Jason.

Jason bit his lip as the Bug spoke.

Then he shook his head determinedly. ‘No way, Bug. I didn’t come here to bow out in the first ten minutes. We’re not out of this yet. You just plot our course, I’ll do the rest.’

And with that, he gunned the thrusters, flinging the

Argonaut

back into the race.

When they had arrived in Pit Lane earlier that morning, Jason and the Bug had sensed an unusual level of excitement in the air.

It was a good crowd - 80,000 bustling spectators taking their places in the giant hover-grandstands overlooking the Gulf.

Of course, this was nothing like the crowds they got at the pro events. There, anything less than a million spectators was seen as a poor showing.

Part of the excitement stemmed from the fact that this year there were five drivers, including Jason, who were in contention to take out the regional championships and thus garner a precious invitation to the International Race School, gateway to the professional circuit.

But it was in Pit Lane itself where the excitement was at its highest.

Everyone was whispering and pointing at the two distinguished-looking gentlemen being shown around the VIP tent by Randolph Hardy, the portly President of the Indo-Pacific Regional Directorate of the IHCRA, the International Hover Car Racing Association.

Whispered voices:

‘Gosh, it’s LeClerq! The Dean of the Race School…’

‘…other one looks like Scott Syracuse, the guy who was in that accident in New York a couple of years ago and almost died…’

‘Someone was saying they’re here to scout for

extra

candidates for the Race School…’

‘No way…’

Jason eyed the two visitors strolling through the VIP tent with Randolph Hardy.

The older man was indeed Jean-Pierre LeClerq, Principal of the International Race School, the most prestigious racing school in the world.

Located in Tasmania - an enormous island at the bottom of Australia that was wholly-owned by the Race School - it was more a

qualifying

school than a strictly teaching institution. While lessons were certainly taught there, it was your ranking in the School Championship Ladder that really mattered. It was that ranking that got you a contract with a pro racing team after your year at ‘the School’. Not surprisingly, the Race School had produced nearly half of the drivers currently on the pro circuit.

LeClerq was a regal-looking fellow, with a perfectly-groomed mane of white hair and an imperious bearing. His suit looked expensive. Jason figured it probably cost more than his entire car did.

The man beside LeClerq was far younger, in his early 30s. He was sort of handsome, with intense features and impenetrable black eyes. He also walked with a cane and looked like he’d rather be at the dentist having root canal therapy than be here at the Indo-Pacific Regional Championships.

Jason recognised him instantly. He had the man’s collector-card in his bedroom back home.

He was Scott J. Syracuse, otherwise known as ‘The Scythe’, one of the best racers ever to have helmed a hover car…until he busted the neurotransmitters in his brain in a horrific crash at the New York Masters three years ago. These days, modern medicine could fix just about any broken bone in your body, even a busted spine, but the one thing man hadn’t figured out was how to fix the human brain. If you busted your brain, your racing career was over, as the Scythe had found out.

And then suddenly Syracuse turned and his ice-cool eyes locked on Jason.

Jason froze, caught staring.

A full second too late, he looked away.

Truth be told, he actually felt embarrassed under Syracuse’s glare. All the other drivers here wore coordinated outfits that matched the colour schemes of their cars. Some even had the new Shoei helmets. Others still had full pit crews wearing their team’s colours. Jason and the Bug, on the other hand, wore denim overalls and their dusty farmboots. They raced in old motorcycle helmets. Jason scowled. He could hide his eyes, but he couldn’t hide his clothes.

He also couldn’t hide his hover car from Syracuse’s level gaze. But that was another story.

The

Argonaut

.

Car No.55.

It was Jason’s pride and joy, and he spent every spare minute he had working on it. It was an old Ferrari Pro F1 conversion that he’d found in a junkyard four years ago - one of those early hover cars converted from old Formula One cars.

It had the bullet-shaped body of an old F1 car, complete with nosewing, hunchbacked fuselage and wide tail rudder, but with the added features of a navigator’s seat tucked immediately behind the driver’s cockpit and a pair of swept-back wings stretching out from its flanks.

Most incongruously for an old F1 car, however, it had no wheels. Hover technology - the six shiny silver discs on its underbelly called

magneto drives

- had made wheels unnecessary.

While he liked to think otherwise, Jason knew it wasn’t a real Ferrari Pro F1. Only the chassis. The rest of it was a hodge-podge of machinery and spare parts that Jason had scrounged from farm vehicles and the local wrecker’s yard. Even its six race-quality magneto drives - a mix of GM, Boeing and BMW mags - were second-hand.

Despite its eclectic innards, the

Argonaut

‘s exterior was beautiful - it was painted blue-white-and-silver in a way that accentuated the car’s fighter-jet-like shape.

Jason himself was 14 years old, blond-haired, blue-eyed and determined. At school, he was good at math, geography and game theory. He wore his sandy-blond hair in a messy ‘mohican’ style reminiscent of the retired English footballer, David Beckham.

At 14, he was also rather young to be at the Regional Championships. Most of the other drivers at this level of racing were 17 or 18. But Jason had finished in the Top 3 in his district trials just like the rest of them, which meant he had as much right to be here as they did.

With him as his navigator was the Bug - his brother, and at 12, even younger. With his tiny body and his big thick-lensed glasses, the Bug confounded a lot of people. He didn’t talk much. In fact, the only people he would speak to were Jason and their mother, and even then only in a whisper. Some of the doctors said that the Bug was borderline autistic - it explained his excessive shyness and social awkwardness while also explaining his mathematical genius. The Bug could tell you what 653 x 354 was…in two seconds.

Which made him the perfect navigator in a hover car race.

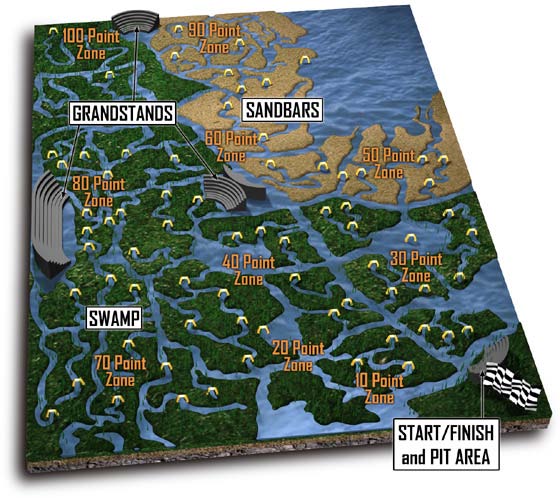

The Carpentaria Race was a ‘gate race’.

The most famous gate race in the world was the London Underground Run - a fiendishly complex race through the tunnels of the London Underground system - and the Carpentaria Race was based on the same principle.

Instead of doing laps around a track, a gate race had no actual track at all. Rather, it took place over a wide area of open terrain 600 km wide by 600 km long. In today’s case, that terrain was the vast swampland on the edge of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria: a marshy landscape that featured a labyrinthine network of narrow waterways cutting through the swamp’s eight-foot-high reed-fields and the high coastal sandbars of the Gulf itself.

Positioned at various points around this maze of natural canals were approximately 250 bridge-like arches through which the racers drove their hover cars. As your car whizzed through a gate-arch, an electronic tag attached to your nosewing recorded the pass.

Passing through a gate gave you points. Gates farther away from the Start-Finish Line were worth more; those that were closer, less. The farthest gate from the Start-Finish Line, for example, was worth 100 points. The nearest, 10 points.

The trick was: there was a strict time limit.

You had three hours to race through as many gates as you could,

and then get back to the Start-Finish Line

. This final element was crucial.

Every

second

that you were late coming back cost you

one point

. So coming home just a minute over the three-hour mark would cost you a massive 60 points.

The driver with the most points won.

Which made it a tactical race in which navigators played a key role.

No driver, no matter how skilled or fast, could get through all the gates in the allotted time - which meant

choosing

which gates to go for within that time limit. And since computer navigation programs were strictly forbidden at all levels of hover car racing, having a good navigator was crucial.