How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character (41 page)

Read How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character Online

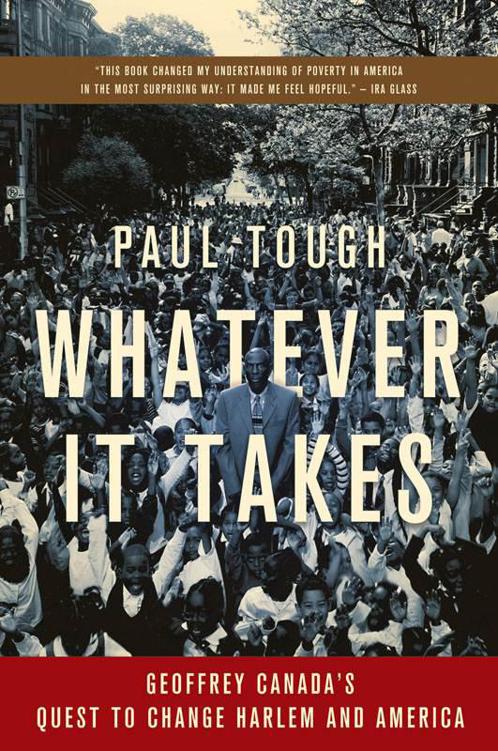

Authors: Paul Tough

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Adult, #Azizex666, #Psychology

But Canada still wasn't quite ready to spin the drum. He called up one last guest: Rev. Alfonso Wyatt, a friend of Canada's since the early 1980s and now a minister on the staff of the Greater Allen Cathedral in Queens. Wyatt was on the school's board of trustees along with Langone and Druckenmiller and Kurz, but not because of his fundraising acumen. He was there for less tangible reasons—a moral authority, maybe, or maybe it was just that unlike the businessmen, all of whom were white, Wyatt shared a culture and a history with Canada: the peculiar joys and sorrows of inner-city black activism in the post–civil rights era. Wyatt and Canada were a decade or two younger than the men who had marched with Martin Luther King Jr., the generation that now made up the nation's civil rights establishment; their perspective was shaped not by Selma and the March on Washington but by what followed: Black Power and busing riots, drugs and AIDS and hip-hop.

Wyatt pulled the microphone from its holder and walked to the front of the stage. He wore a white turtleneck under a dark suit jacket, a modified version of a clerical collar. A stylized cross hung around his neck. "Some people don't believe that there are folks in Harlem who really care about their children," he began, his voice a sonorous baritone, his cadence deliberate, straight from the pulpit. "They don't believe that on a day when it was raining all day, that they would come out and that they would sit and that they would wait. People don't believe that there are folks who don't mind being inconvenienced." As he warmed up, the attention of the crowd, which had been wandering, was pulled back to the front of the auditorium. "But I know that the people here in this room don't mind waiting. Because if they can wait a

little

while tonight, they can change their children's life over the

long

while." Wyatt began pacing the stage, and suddenly even the people who did mind waiting didn't mind waiting. "So I want to salute you," he said. "We're going to show people all over the world that with a good staff, with dedication, with teamwork, that we can turn out first-rate scholars" There was a loud burst of applause. "Oh, you

better

clap," Wyatt continued. "We're not cutting no corners. We're going to

do

this." He pulled out one of his favorite stories, one he often used in front of a crowd like this one. "I want to tell you something that maybe you don't know," he said, his voice rising. "The people who run prisons in this country are looking at our third-graders. They look at their test scores each year to begin to predict how many prison cells will be needed twenty years from now." Some scattered murmurs of disapproval were heard. "And so I want the people in this house to tell them: You will not have our children!" The applause was louder now, a Sunday-morning feel on a wet Tuesday night.

"Let me hear somebody say it," Wyatt called out, and he led the crowd in a chant: "You! Will! Not! Have! Our! Children!"

"Let me hear somebody else say it," Wyatt cried, and the parents shouted again, louder:

"You! Will! Not! Have! Our! Children!"

"Let's make some noise in this place!"

AND THEN THE

drawing began, starting with the kindergarten class. Doreen Land, the academy's newly hired superintendent, read the first name into a microphone: "Dijon Brinnard." A whoop went up from the back of the auditorium, and a jubilant mother started edging her way out of her row, proudly clutching the hand of her four-year-old son. Land smiled and took the next card: "Kasim-Seann Cisse." Another whoop, some applause, and then, a few seconds later, "Yanice Gillis." Yasmin Scott clapped her hands and leapt to her feet.

At the front of the auditorium, Canada congratulated each mother (or, occasionally, father) and child. Proud parents shook his hand and introduced their children, beaming on their way back to their seats. In the front row, Wilma Jure was praying harder than ever, her eyes shut tight, her lips moving, reciting one supplication after another. And then Land read out, "Jaylene Fonseca," and Jure's eyes flew open, and the next thing she knew, she was on her feet, hugging Canada, tears brimming in her eyes, and then running out of the auditorium to call her sister with the good news.

As the evening wore on, though, the mood in the auditorium started to shift. The kindergarten lottery ended, the chosen students trooped out to the cafeteria for a group photo, and the sixth-grade lottery began. In the front row, Virainia Utley sat with her daughter Janiqua, listening to the names and trying not to worry. But the lottery numbers were rising—fifty-four, fifty-five, fifty-six—and Janiqua hadn't yet been called.

After Land read out the one hundredth name, Canada took the stage again and explained to Utley and the other remaining parents that it wasn't likely there would be room for their children in the sixth grade. Land would read out the rest of the names and put them on a waiting list, he said, but this part wouldn't be much fun. He encouraged everyone to go home. Land went back to reading names, and Utley and Janiqua sat and listened, still in their seats, as the waiting list grew and the number of cards in the drum dwindled. By the time Land got to the eightieth place on the waiting list, they were just waiting to make sure Janiqua's name was called. Maybe her card got lost or stuck to another card.

The room was thinning out, and the only remaining parents were angry ones. They were lining up to let Canada know how they felt. One by one, the parents came up to him to find out what could be done to get their children into the school, and he had to tell each one the same thing: nothing. Nothing could be done. One disappointed woman spat out her complaint to anyone who would listen. "I think it's not fair, and I want someone to know," she said, her voice loud and bitter. "It's

very

unfair. Drag people out and they sit here all day, half their night is gone—they can't cook dinner, they can't do nothing—because they said that our child's going to get in here, and then our child don't get in here. But we're still sitting here, waiting to do what? On a wait list? It's not fair, and I don't like it."

Finally, at number 111 on the waiting list, Janiqua Utley's name was called, and her mother rose, took her by the hand, and started up the aisle to the back door.

AS WORKERS BEGAN

sweeping up coffee cups and deflated balloons, I sat down next to Canada in the front row of the auditorium, off to the side. I had by this point been reporting on his work for almost a year, following him to meetings and speeches and events around the city. But I had never seen him look so exhausted; he was overwhelmed, it seemed, not only by the emotion of the evening but also by the enormity of the task ahead of him.

"I was trying to get folks to leave and not to hang around to be the last kid called," he said. "This is very hard for me to see. It's very, very sad. People are desperate to get their kids into a decent school. And they just can't believe that it's not going to happen." His eyes were watery, and as we talked he dabbed periodically at his nose with his folded-up handkerchief. "These parents really get it," he said. "They understand that if the school is good, the odds that your child is going to have a good life just increase exponentially. So now they just feel, 'Well, there go my child's chances.'"

Canada often spoke of a "competition" that was going on in New York City, and by extension in the nation, between the children he called "my kids," the thousands of children who were growing up in Harlem in poverty, and the kids living below 110th Street, mostly white, mostly well off, with advantages visible and invisible that shadowed them wherever they went. The divisions between these two populations had grown more stark than ever. The average white family in Manhattan with children under five now had an annual income of $284,000, while their black counterparts made an average of $31,000. Growing up in New York wasn't just an uneven playing field anymore. It was like two separate sporting events.

"For me," Canada said, "the big question in America is: Are we going to try to make this country a true meritocracy? Or will we forever have a class of people in America who essentially won't be able to compete, because the game is fixed against them?" Canada's voice sounded raspy and solemn. "There's just no way that in good conscience we can allow poverty to remain the dividing line between success and failure in this country, where if you're born poor in a community like this one, you stay poor. We have to even that out. We ought to give these kids a chance."

The creation of the Harlem Children's Zone had brought Canada to a strange new moment in his life. He had known since he was a child that this was the work he wanted to do. In college, he was a political activist, and he led angry demonstrations against the injustices that he and other black students saw on campus and in the nation. He went to work as a teacher after graduation, and for thirty years now he had been a passionate advocate for children. It was a very emotional business he was in, and the approach that he and many of his peers had always taken was an intensely personal one: if you could reach one child, touch one life, your work was worthwhile. But the old way of doing things wasn't working for Canada anymore, or at least it wasn't working fast enough. He had seen it happen over and over: you reach one child and ten more slip past you, into crime or substance abuse or just ignorance and indolence, menial jobs, long stretches of unemployment, missed child-support payments. Saving a few no longer felt like enough.

"We're not interested in saving a hundred kids," Canada told me. "Even three hundred kids. Even a thousand kids to me is not going to do it. We want to be able to talk about how you save kids by the tens of thousands, because that's how we're losing them. We're losing kids by the tens of thousands."

In starting the Harlem Children's Zone, Canada was asking a new set of questions: What would it take to change the lives of poor children not one by one, through heroic interventions and occasional miracles, but in a programmatic, standardized way that could be applied broadly and replicated nationwide? Was there a science to it, a formula you could find? Which variables in a child's life did you need to change, and which ones could you leave as they were? How many more hours of school would be required? How early in a child's life did you need to begin? How much did the parents have to do? How much would it all cost?

The questions had led Canada into uncharted territory. His new approach was bold, even grandiose: to transform every aspect of the environment that poor children were growing up in; to change the way their families raised them and the way their schools taught them as well as the character of the neighborhood that surrounded them. But Canada had come to believe that it was not only the best way to solve the relentless problem of poverty in America; it was the only way. Across the country, policymakers, philanthropists, and social scientists were carefully watching the system that Canada was building in Harlem. The evidence that he was trying to create, they knew, had the potential to reshape completely the way that Americans thought about poverty.

Canada realized that if he was going to make this new approach work, he couldn't take each child's success and failure as personally as he used to. Promise Academy was a crucial new step, but it was just one link in the chain that Canada was constructing, and he knew he needed to stay focused on the big picture. It wasn't easy for him, though, especially on nights like this one. For all his attempts to be cold-hearted and analytical, when he looked into the eyes of the parents he was turning down, he still felt the pain in their lives viscerally. At the end of what was supposed to be a triumphant event, he couldn't shake the feeling that he wasn't doing enough, that he had failed.

"What I'm going to remember about tonight," he said, "is how those mothers looked at me when their kids didn't get in." It made him think about his own young son, Geoffrey Jr., who was at home with his mother, Canada's wife, Yvonne. "When I go home tonight to my own kid, whose life is pretty much secure," Canada said, "it's not going to make me sleep well knowing there are kids and families out there that

don't

feel secure. They just are terrified that their child is not going to make it, and they think this is another opportunity that slipped by."

It was a waiting list that had started him on the path to the Harlem Children's Zone a decade earlier. And now, despite everything he had accomplished and all the millions he had spent, here he was, still setting up waiting lists. "We've got to do more," he said with a sigh. "We've got to give these people a chance for hope."

Buy the Book

Visit

www.hmhbooks.com

or your favorite retailer to purchase the book in its entirety.

About the Author