How Hitler Could Have Won World War II (5 page)

The attack got little artillery and no air support.

Rommel's 7th Panzer Division had arrived south of Arras, and he swung his tanks around northwest of Arras on the morning of May 21. The division's artillery and infantry were to follow.

The British, not realizing that the German tanks had passed beyond them, formed up west of Arras in the afternoon and attacked southeast, intending to sweep to the Cojeul River, a small tributary to the Scarpe, five miles southeast of the city, and destroy any enemy in the sector.

South and southwest of Arras, the British ran into Rommel's artillery and infantry, minus their tanks, and began to inflict heavy casualties. The Germans found their 37-millimeter antitank guns were useless against the Matildas. The British tanks penetrated the German infantry front, overran the antitank guns, killed most of the crews, and many of the infantry, and were only stopped by a frantic effortâundertaken by Rommel himselfâto form a “gun line” of field artillery and especially high-velocity 88-millimeter antiaircraft guns, which materialized as a devastating new weapon against Allied tanks. The artillery and the “88s” destroyed thirty-six tanks and broke the back of the British attack.

Meanwhile, the panzers turned back on radioed orders from Rommel and arrived on the rear and flank of the British armor and artillery. In a bitter clash of tank on tank, Rommel's panzer regiment destroyed seven Matildas and six antitank guns, and broke through the enemy position, but lost three Panzer IVs, six Panzer IIIs, and a number of light tanks.

The British fell back into Arras and attempted no further attack.

The Allied effort had been too weak to alter the situation, but showed what could have been done if the Allied commanders had mobilized a major counterattack. Even so, the British effort had wide repercussions. Rommel's division lost 387 men, four times the number suffered until that point. The attack also stunned Rundstedt, and his anxiety fed Hitler's similar fears and led to momentous consequences in a few days.

On May 22, Guderian wheeled north from Abbéville and the sea, aiming at the channel ports and the rear of the British, French, and Belgian armies, which were still facing eastward against Bock's Army Group B. Reinhardt's panzers kept pace on the northeast. The next day, Guderian's tanks isolated Boulogne, and on May 23, Calais. This brought Guderian to Gravelines, barely ten miles from Dunkirk, the last port from which the Allies in Belgium could evacuate.

Reinhardt also arrived twenty miles from Dunkirk on the Aa (or Bassée) Canal, which ran westward past Douai, La Bassée, and St. Omer to Gravelines. The panzers were now nearer Dunkirk than most of the Allies.

While the right flank of the BEF withdrew to La Bassée on May 23 under pressure of a thrust northward by Rommel from Arras toward Lille, the bulk of the British forces moved farther north to reinforce the line in Belgium. Here Bock's forces were exerting increasing pressure, causing King Leopold to surrender the Belgian army the next day.

Despite this, Rundstedt gave Hitler a gloomy report on the morning of May 24, laying emphasis on the tanks the Germans had lost and the possibility of meeting further Allied attacks from the north and south. All this reinforced Hitler's own anxieties. He showed his paranoia by saying he feared the panzers would get bogged down in the marshes of Flanders, though every tank commander knew how to avoid wet areas.

Hitler had been extremely nervous from the start of the breakthrough. Indeed, he became

more

nervous the more success the Germans gained, worrying about the lack of resistance and fearing a devastating attack on the southern flank. He had not grasped that Manstein's strategy and Guderian's brilliant exploitation were bringing about the most overwhelming decision in modern military history. The Germans had been out of danger from the first day, but to Hitler (and to most of the senior German generals) it seemed too good to be true.

The question now arose of what to do about the British and French armies in Belgium. With virtually no enemy forces in front of them, Guderian and Reinhardt were about to seize Dunkirk and close off the last possible port from which the enemy troops could embark. This would force the capitulation of the entire BEF and the French First Group of Armies, more than 400,000 men.

At this moment, the war took a bizarre and utterly bewildering turn. Why events unrolled as they did has been disputed ever since, and no one has come close to understanding the reasons.

Hitler called in Walther von Brauchitsch, the army commander in chief, and ordered him to halt the panzers along the line of the Bassée Canal. Rundstedt protested, but received only the curt telegram: “The armored divisions are to remain at medium artillery range from Dunkirk [eight or nine miles]. Permission is only granted for reconnaissance and protective movements.”

Kleist thought the order made no sense, and he pushed his tanks across the canal with the intention of cutting off the Allied retreat. But he received emphatic orders to withdraw behind the canal. There the panzers stayed for three days, while the BEF and remnants of the 1st and 7th French Armies streamed back to Dunkirk. There they built a strong defensive position, while the British hastily improvised a sea lift.

The British used every vessel they could find, 860 in all, many of them civilian yachts, ferryboats, and small coasters. The troops had to leave all their heavy equipment on shore, but between May 26 and June 4 the vessels evacuated to England 338,000 troops, including 120,000 French. Only a few thousand members of the French rear guard were captured.

Two seemingly plausible reasons have been advanced for Hitler's decision. One is that Hermann Göring, one of his closest associates and chief of the Luftwaffe, promised that he could easily prevent evacuation with his aircraft, since the panzers were needed to turn south and begin the final campaign to defeat France. The other is that Hitler wanted a settlement with Britain and deliberately prevented the destruction of the BEF to make peace easier to attain. Regardless of which motivations impelled Hitler, he made the wrong judgment. The Luftwaffe did a poor job, and the British were uplifted by the “miracle of Dunkirk,” redoubling their resolve to fight on.

The Luftwaffe started late, not mounting a strong attack until May 29. Air attacks increased over the next three days, and on June 2 daylight evacuation had to be suspended. But RAF fighters valiantly tried to stop the bombing and strafing runs, and were in part successful. The beach sand absorbed much of the blast effects of bombs. The Luftwaffe did most of its damage at sea, sinking 6 British destroyers, 8 transport ships, and more than 200 small craft.

Hitler lifted the halt order on May 26, but soon thereafter army headquarters directed the panzers to move south for the attack across the Somme, leaving to Army Group B's infantry the task of occupying Dunkirkâafter the Allies had gone.

On June 4, Winston Churchill rose to speak in the House of Commons. He closed his address with these words that inspired the world:

We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight in the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing-grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall

never

surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God's good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the Old.

The end in France came swiftly. In three weeks, the Germans had captured more than a million prisoners, while suffering 60,000 casualties. The Belgian and Dutch armies had been eliminated, and the French had lost thirty divisions, nearly a third of their total strength, and this the best and most mobile part. They had also lost the assistance of eight British divisions, now back in Britain, with most of their equipment lost. Only one British division remained in France south of the Somme.

Weygand was left with sixty-six divisions, most of them understrength, to hold a front along the Somme, the Aisne, and the Maginot Line that was longer than the original. He committed forty-nine divisions to hold the rivers, leaving seventeen to defend the Maginot Line. Most of the mechanized divisions had been lost or badly shattered. However, the Germans quickly brought their ten panzer divisions back to strength and deployed 130 infantry divisions, only a few of which had been engaged.

The German high command reorganized its fast troops, combining armored divisions and motorized divisions in a new type of panzer corps, generally with one motorized and two armored divisions to each corps.

OKH promoted Guderian to command a new panzer group of two panzer corps, and ordered him to drive from Rethel on the Aisne to the Swiss frontier. Kleist kept two panzer corps to strike south from bridgeheads over the Somme at Amiens and Péronne, but these later shifted eastward to reinforce Guderian's drive. The remaining armored corps, under Hoth, was to advance between Amiens and the sea.

The offensive opened on June 5, and France collapsed quickly. Not all the breakthroughs were easy, but the panzers, generally avoiding the villages and towns where defenses had been organized, were soon ranging across the countryside almost at will, creating chaos and causing the French soldiers to surrender by the hundreds of thousands.

An example was Erwin Rommel's 7th Panzer Division, which crossed the Somme near Hangest east of Abbéville on June 5, and moved so fast and materialized at points so unexpectedly that the French called it the “ghost division.” On June 6, at Les Quesnoy, the entire division lined up on a 2,000-yard front, with the 25th Panzer Regiment in the lead, and advanced across country as if on an exercise. Two days later it reached the Seine River, eleven miles southeast of Rouen, a drive of seventy miles, then turned northwest and raced to the sea at St. Valéry, where it captured the British 51st Highland Division.

Guderian's panzers cut off northeastern France with a rapid drive to the Swiss frontier. The troops defending the Maginot Line retreated and surrendered almost without firing a shot.

With victory over France assured, Italy entered the war on June 10. The same day President Franklin D. Roosevelt was speaking at commencement at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Roosevelt reversed his usual emphasis on avoiding American involvement in the war and promised to extend aid “full speed ahead.” But his address is most remembered for his condemnation of Italy for striking “a dagger into the back of its neighbor.”

The Germans entered Paris on June 14 and reached the Rhône valley on June 16. The same night the French asked for an armistice, and on June 17 Reynaud resigned as premier and was succeeded by Marshal Philippe Pétain. While talks went on, German forces advanced beyond the Loire River. At the same time, a French light cruiser took to safety 1,754 tons of gold from the banks of France, Belgium, and Poland, while, under the direction of British Admiral William James, ships at numerous French ports carried to England nearly 192,000 men and women (144,171 Britons; 18,246 French; 24,352 Poles; 4,938 Czechs; and 162 Belgians). Many of the French joined a new Free French movement under Charles de Gaulle, who had arrived in Britain, vowing to fight on against the Germans.

On June 22 the French accepted the German terms at Compiègne, in the same railway car where the defeated Germans had signed the armistice ending World War I in 1918. On June 25 both sides ceased fire. The greatest military victory in modern times had been achieved in six weeks.

4 HITLER'S FIRST GREAT ERROR

THE SWIFT GERMAN VICTORY OVER FRANCE AND THE EJECTION OF THE BRITISH Expeditionary Force from the Continent without its weapons raised the immediate question of whether Britain could survive.

The obvious answer was what the world expected: German forces would sweep over the narrow seas and conquer the British isles as quickly as they had shattered France. There was only one impediment: Germany had to achieve at least temporary air and sea supremacy over and on the English Channel. Otherwise, ferries, barges, and transports carrying troops could be easily sunk by Royal Navy ships before they could land on English beaches and docks.

The crucial requirement was in the air. German navy leaders believed they could shield landing craft and ships for the short passage, but only if British warships could not run in at will among the convoys. This could be assured only if the Luftwaffe ruled the skies above the invasion fleet, and could bomb and strafe any enemy ship that showed itself.

Hitler was reluctant to invade Britain, thinking the British would come to their senses, recognize their “militarily hopeless situation,” and sue for peace.

He persisted in this view in spite of a speech by Winston Churchill in the House of Commons on June 18, 1940, four days before France gave up. “The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us,” Churchill said. “Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. . . . Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will say, âThis was their finest hour.' ”

Shortly thereafter, Hitler got a swift lesson in British determination to continue the war.

The Germans had occupied three-fifths of France, including the whole Atlantic coast, leaving the remainder unoccupied with a government under Marshal Pétain centered in the resort town of Vichy. The big question was what would become of the French fleet. Most of it moved into the French Mediterranean harbor of Toulon, but powerful elements remained in North Africa.

Churchill's government feared a change in the balance of power if even a part of the French fleet got into German hands. The British wanted to take possession of it or eliminate it.

In surprise moves on July 3, 1940, British troops seized French ships that had taken refuge in British harbors, and a powerful British naval group including three battleships and an aircraft carrier under Admiral Sir James Somerville arrived at Oran and Mers-el-Kebir in Algeria, where the largest French flotilla outside Toulon lay at anchor.

Somerville tried to get the French to surrender, but failed, and the British opened fire on their former allies. The battleship

Bretagne

blew up, the

Dunquerque

ran aground, the battleship

Provence

beached, and the torpedo cruiser

Magador

exploded. The battleship

Strasbourg

and three heavy destroyers were able to run out to sea, break through the British ring of fire, and reach Toulon, as did seven cruisers berthed at Algiers. Almost 1,300 Frenchmen died in the Mers-el-Kebir battle. Five days later torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier

Hermes

seriously damaged the French battleship

Richelieu

at Dakar in Senegal.

The British attacks enraged France, but brought before the eyes of people everywhere the striking power of the Royal Navy. It helped to convince President Roosevelt and the American people that backing Britain was a good bet.

Hitler still waited until July 16 before ordering an invasion, named Operation Sea Lion. He said, however, that the undertaking had to be ready by mid-August.

Hermann Göring assured Hitler that his Luftwaffe could drive the Royal Air Force out of the skies in short order. The invasion depended upon Göring's word.

Britain had only 675 fighter planes (60 percent Hurricanes, 40 percent Spitfires) combat-ready when the battle started. Germany had 800 Messerschmitt 109s to protect its 875 two-engined bombers and 316 Stukas. It also had 250 two-engined Messerschmitt 110 fighters, but these were 60 miles per hour slower than Spitfires, and turned out to be a great disappointment.

The Messerschmitt (or Bf) 109 had a top speed of 350 miles per hour. It was armed with three 20-millimeter cannons and two machine guns. Approximately equal was the British Supermarine Spitfire with a maximum speed of 360 mph and armed with eight machine guns. Somewhat inferior was the British Hawker Hurricane with a top speed of 310 mph, a slower rate of climb, eight machine guns, but more robust and easier to maintain. The 1940 model Hurricane could reach 330 mph and carried four 20-millimeter cannons. The Me-109 and the Spitfire both had a maximum range of about 400 miles, the Hurricane 525 miles.

Aircraft numbers were closely guarded secrets, but leaders everywhere had good estimates of the comparative strengths of the two sides, and few were betting on the British.

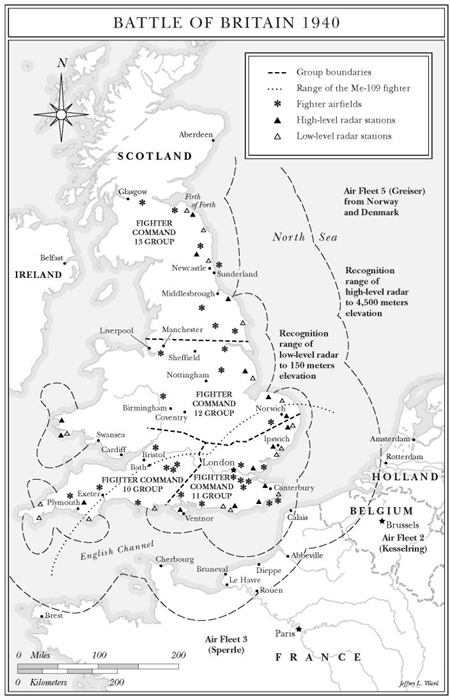

Göring concentrated his fighters and bombers for an all-out assault on airfields and fighters in southern England. He and other Luftwaffe leaders didn't realize that the RAF's greatest strength was not its fighter aircraft, vital as they were, but the new British-developed radar, which sent out radio signals that struck incoming aircraft and reflected them back to receiving stations. By 1940 Britain had a double line of radar stations facing the Continent. One line consisted of receivers on high towers that could detect high-flying enemy aircraft 120 miles away. The other had a shorter range but could pick up low-flying aircraft.

The radar net, combined with Observer Corps spotters on the ground who tracked aircraft once past the coast, gave the RAF advance warning of approaching bombers. The skill of RAF Fighter Command was based on shrewd use of radar. From the moment they took off from bases in western Europe, German aircraft were spotted on screens, their courses plotted. Fighter Command knew exactly where and when they could be attacked.

RAF fighters could mass against each German wave, and also climb into the air just before they had to engage, thus preserving fuel. By comparison, Messerschmitts could remain protecting bombers over England only for minutes because they had to fly from the Continent and back.

In the days leading up to the start of the main campaign, Eagle Day on August 13, Stukas struck repeatedly at airfields and radar stations, and on August 12 knocked out one radar station. But the Germans didn't know how vital radar was and didn't concentrate attacks on it. The strikes showed that the Stukas were too slow and vulnerable for the long-range mission against Britain, and had to be withdrawn.

On August 13 and 14, three waves of German bombers, a total of 1,500 sorties, damaged several RAF airfields, but destroyed none. The strongest effort came on August 15 when the Germans launched 800 bombing and 1,150 fighter sorties. A hundred bombers escorted by Me-110s from Air Fleet 5 in Scandinavia, expecting to find the northeastern coast of Britain defenseless, instead were pounced on by Hurricanes and Spitfires as they approached Tyneside. Thirty aircraft went down, mostly bombers, without a British loss. Air Fleet 5 never returned to the Battle of Britain.

In southern England the Luftwaffe was more successful. In four attacks, one of which nearly penetrated to London, bombers hit four aircraft factories at Croydon, and damaged five fighter fields. But the Germans lost 75 planes, the RAF 34.

On August 15, Göring made his first major error. He called off attacks on the radar stations. But by August 24 he had learned about the second key to the RAF defense, the sector stations. These nerve centers guided fighters into battle using latest intelligence from radar, ground observers, and pilots in the air. He switched to destruction of these stations. Seven around London were crucial to protection of southern England.

From that day to September 6, the Luftwaffe sent over an average of a thousand planes a day. Numbers began to tell. They damaged five fields in southern England badly, and hit six of the seven key sector stations so severely that the communications system was on the verge of being knocked out.

The RAF began to stagger. Between August 23 and September 6, 466 fighters were destroyed or badly damaged (against 352 German losses). Although British factories produced more than 450 Spitfires and Hurricanes in both August and September, getting them into squadrons took time. And the real problem was not machines but men. During the period 103 RAF pilots were killed and 128 seriously wounded, one-fourth of those available. A few more weeks of such losses and Britain would no longer have an organized air defense.

At this moment, Adolf Hitler changed the direction of the battleâand the war. If he had allowed the Luftwaffe to continue its blows to the sector stations, Sea Lion could have been carried out and Hitler could have ended the war with a swift and total victory. Instead, he made the first great blunder in his career, a blunder so fundamental that it changed the course of the entire conflictâand set in motion a series of other blunders that followed in its wake.

So far as can be determined from the evidence, Hitler made this devastating mistake because of anger, not calculation.

In addition to the sector stations, Göring had been attacking the British air-armaments industry, which meant that industrial cities were suffering substantial damage. Then, on the night of August 24, ten German bombers lost their way and dropped their loads on central London. RAF Bomber Command launched a reprisal raid on Berlin the next night with eighty bombersâthe first time the German capital had been hit. Bomber Command followed up this raid with several more in the next few days. Hitler, enraged, announced he would “eradicate” British cities. He called off the strikes against sector stations and ordered terror bombing of British cities.

This abrupt reversal of strategy did not rest entirely on Hitler's desire for vengeance. The new campaign had a lengthy, highly touted theoretical background. It was the first extensive experiment to test the “strategic-bombing” theory espoused after World War I by an Italian, Giulio Douhet. His argument was that a nation could be forced to its knees by massive bombing attacks against its centers of population, government, and industry. Such attacks would destroy the morale of the people and war production, and achieve victory without the use of ground forces.

The Luftwaffe's original operation against British airfields, sector stations, and aircraft factories was a variation on the highly successful battles it had won in May and June, which eliminated most of the French air force and shot down or contained the few RAF aircraft on the Continent. This was essentially a tactical campaign to gain supremacy for military forces on the ground.

The second campaign was entirely different. It aimed not at winning a battle but at destroying the morale of the enemy population. If it succeeded, as Douhet had predicted, an invasion of Britain would not even be necessary. The disheartened, defeated people of Britain would raise the white flag merely to stop the bombing.

Hitler was the first to attempt Douhet's theory, but his bombs failed to break the British people. World War II proved that human beings can endure a great deal more destruction from the skies than Douhet had thought.

On the late afternoon of September 7, 1940, 625 bombers and 648 fighters flew up the Thames River and bombed docks, central London, and the heavily populated East End, killing 300 civilians and injuring 1,300. The fires raging in the East End guided the second wave of bombers that night. Waves of bombers came in repeatedly until 5 A.M. the next day. The assault went on night after night.

On the morning of Sunday, September 15, the Germans sent in a new daylight attack. Although British fighters assailed the air armada all the way from the coast, 148 bombers got through to London. As they turned for home, sixty RAF fighters swept down from East Anglia and destroyed a number of the bombers. The Germans lost sixty aircraft, against twenty-six British fighters. Because the costs were so high, the Luftwaffe soon shifted over entirely to night attacks, concentrating on London, which it struck for fifty-seven straight nights, averaging 160 bombers a night. On September 17, Hitler called off Sea Lion indefinitely.