How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (31 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

‘I got The Smiths’, says Geiger, ‘booked their first tour, then Ian Copeland, who had been my mentor in many ways, took them on. He was better at hanging with Scott Piering and Mike Hinc. I think it had to do with Charlie but I don’t know a guy named Charlie … and I’m not a Charlie person … never was … anyway … There was a lot of Charlie going on at the time.’

Geiger was not the only ally of the band frustrated at their inability to maintain a working relationship with a manager for more than six months. By the time The Smiths made their second and final tour of the States in 1986, they were capable of selling out two nights at Universal Amphitheatre in LA in a matter of hours, putting them on the cusp of the stadium league and in desperate need of a support infrastructure that could build on their momentum, something, since the retirement of Joe Moss, they had singularly failed to do. The result was a series of cancelled dates, including the last four shows on the ’86 American tour, one of which was a prestigious New York date

where Stein and Sire had prepared an end-of-tour wrap party in the style only Stein knew how to throw. While the situation was frustrating for an American music industry finely tuned to notice when an opportunity was being so clearly missed, at home the band’s relationship with Rough Trade was starting to unravel.

Cracks had first begun to appear in the summer of 1985 when Morrissey insisted that ‘That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore’ be released as a single from

Meat Is Murder

, considering both ‘How Soon Is Now?’ and ‘Shakespeare’s Sister’, two non-LP tracks, had already been released since the album came out; it was a curious decision that went against industry practice and common sense.

‘I said to him, “That’s not a good idea,”’ says Travis. ‘“It’s a bad idea, it’s not a single,” and he wouldn’t have that and, being me, I said, “Fine, you want it to come out, it’ll come out.” It came out, it got to no. 34. “Rough Trade are useless.” Of course we are, that proves it. That was the first moment I can remember of any friction.’

Begun around the time of the release of ‘That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore’, the band’s next album,

The Queen Is Dead

had been recorded in extraordinary circumstances. Gossip around the band hinted that The Smiths would soon be leaving Rough Trade. In an act of hardball brinkmanship of which any major would have been proud, Rough Trade placed a high court injunction on the band recording for any other record company. The value of The Smiths to Rough Trade and the fragility of the band’s working relationship with them was now a matter of public record.

Ensuring that Rough Trade would be able to release another Smiths record by pursuing the matter through the law courts was one of the few options left to Travis; The Smiths’ career was reaching breaking point and internal communication over the band’s finances had ended in stalemate. Rather than agree on a

way forward, Morrissey and Marr externalised their problems, laying them all at the feet of their record company.

‘The moaning came after they began to think they were a bigger band than they really were,’ says Travis. ‘It got really mad towards the end, cancellations, releases approved then disapproved, it was chaos.’

The tensions between Travis and The Smiths were accentuated by the closeness of their relationship. Apart from Morrissey’s concentrated and lengthy phone calls with The Smiths’ artwork supervisor, Jo Slee, it was left to Travis to deal directly with the band, an arrangement, in the absence of any kind of mediator, that was becoming increasingly difficult and personal.

Remarkably, in the middle of such constant turmoil The Smiths released their masterpiece

The Queen Is Dead

. Aside from ‘Frankly Mr Shankly’, a thinly disguised open letter to Travis from Morrissey outlining his grievances, there were few signs within the record of the travails that had been the background to its creation.

‘Whenever there was a problem, there was no one around The Smiths that you could just go to and say, “There’s this happening, what do we do, what do you do?”’ says Richard Boon. ‘Everything was diffuse. Other than Mike Hinc, who I think the band had a lot of faith in, and Scott Piering’s on–off attempts to manage them, the reality was, we just thought, Morrissey goes home and talks to his mum about this. And Johnny ends up booking the van. There were issues about control between the two of them; they weren’t ever going to get a manager either of them were happy with, Ken Friedman being a case in point.’

Ken Friedman was the last manager The Smiths appointed, a young and bright West Coast protégé of Bill Graham. With a reputation for being something of a bon viveur, he was in the perfect position to consolidate the band’s profile in the States

and bring some straight-talking Californian ruthlessness into The Smiths’ dealings with Rough Trade.

*

Having resolved the impasse of the court injunction by agreeing a compromise to let the band record one more album for Rough Trade (the contract had previously stated two), Travis was expecting one last Smiths studio album to follow

The Queen Is Dead

. It was quietly pointed out to him via the offer of a buy-out from the major that EMI were The Smiths’ preferred label to release the forthcoming

Strangeways Here We Come

. An increasingly isolated Travis remained tenacious and turned down the offer from EMI.

Strangeways

would be coming out on Rough Trade whether the band liked it or not. It was obvious to all parties that the astonishing trajectory that had been shared by Travis and the band since they walked into Blenheim Crescent had come to an end. ‘In the time I was at Rough Trade, and I was there every day for a year and a bit during the height of their success, I never remember the band coming in the office,’ says Cerne Canning.

Marr in particular had been frustrated by the limits of Rough Trade’s recording budgets, something that the label had failed to prioritise. ‘It was one of the label managers,’ says Boon, ‘Simon Harper I think. He was being driven around London on the back of a courier bike, knocking on studio doors asking if they’d accept payment for a Smiths session by credit card. It had gone beyond a joke – it really wasn’t funny any more – they always thought they weren’t being looked after, and they’d make demands and throw tantrums.’

The Smiths’ increasingly impulsive behaviour could turn on a whim or at the hint of any perceived slight, especially any on the

part of Rough Trade. The last year of their career was a series of botched sessions and cancelled appearances, including turning down such prime-time TV appearances as

Wogan

, which earned the band a reputation, particularly at Collier Street, of remote, rock-star behaviour.

‘There were always completely unfounded rumours of Rolls Royces,’ says Canning. ‘It was like one of those films where the camera followed one person then changed POV as it walked past someone else. Rumours every day, lots of fragments of conversation and people shaking their heads.’

The reality was that the band, particularly Marr, who tried to keep a hands-on grasp on organising the day-to-day

arrangements

of the band, were exhausted. ‘Because we were young and immature, the nature of The Smiths meant we would’ve taken the effects of Rough Trade’s precariousness and been

hotheaded

about it,’ he says. ‘They were learning too, they weren’t necessarily that old as a company either.’

Ken Friedman, who had helped Simple Minds reach

near-arena

status in America, had anticipated that an injection of optimism and industry ambition into The Smiths would help facilitate a new and healthy relationship between the band and EMI as they embarked on the next stage of their career. If Friedman detected a willingness to finally start playing the game and abandon the haphazard point-scoring which had become the main feature of the band’s relationship with Rough Trade, then he was the only person who did.

‘We could never understand why they never wanted to make videos, because at that point the Eighties was being led by video,’ says Boon. ‘They wanted 60 × 40 fly posters all over the place, but there was only so much promotion they were prepared to do. They would turn around and say, “Shakespeare’s Sister” wasn’t a hit cause you’re not promoting us,’ but they weren’t giving us the

tools to promote the product.’

†

At Collier Street the departure of The Smiths was blamed squarely on Travis. Distribution would be losing its biggest-selling catalogue and the tension between the label and distribution had disintegrated into a complete lack of communication as Rough Trade’s internal politics turned venal.

‘Rough Trade’s deal with its own distribution company was the worst of any indie label in the world,’ says Travis. ‘We were on 28 per cent when Mute was probably on 12 per cent, so I mean, thank you, distribution. For every Smiths record that we were selling, they were making a fortune. The kind of characterisations – distribution was the golden egg and the record company’s run by this lunatic that’s spending all our money – that were definitely abroad – it’s just complete nonsense as far as I’m concerned.’

Marr had noticed the factionalising within Rough Trade first-hand, as his phone calls were passed around various staff members in an attempt to resolve the never-ending mess of loose ends and unpaid studio bills.

‘The last thing you imagine in any business is things getting so big that it becomes difficult for you to steer it,’ says Marr. ‘We became all four engines of Rough Trade and we hit turbulence. A lot of it’s to do with there not being enough people in that company, and that they became totally dependent on one band.’

The irony of the Rough Trade middle management’s attempts to rationalise the company along the lines of the critical path and

to create a structure that was not over-reliant on The Smiths is not lost on Travis. ‘I think it just attracted people who thought, “This is glamorous. I can make lots of money,”’ he says. ‘We grew too big and grew out of our control and we weren’t experienced to be able to say, “You know what, this has got too big, we’re out of our depth.” I suppose we were trying to say we’re out of our depth by bringing in new people but unfortunately they weren’t the right people. We weren’t experienced enough to know how to get the right people with those kind of backgrounds and perhaps they didn’t really exist.’

However painful a denouement, the fact remained that during their lifetime The Smiths’ entire canon was released on Rough Trade, and the band and the label represent the perfect symbiosis of independence. The Smiths and Rough Trade grew out of proportion together, cutting a magnificent dash through the Eighties. The band pulled Rough Trade into the mainstream with them. In turn only an independent label would have let The Smiths call their album

The Queen Is Dead

, and only Travis would have understood why that was the record’s title.

From the band’s first brushes with the media in which Morrissey’s lyrics and opinionated playfulness sparked

controversy

to its ending in wilful and chaotic unprofessionalism, their arc could only have been achieved in the spirit of conspiracy that had been created by Travis, Marr and Morrissey. If Travis maintains the band thought they were a bigger group than they actually were, it was their ambition and self-confidence along with their inimitable DNA, as a group and a songwriting partnership, that set them apart from their contemporaries.

‘I think the simple way of putting it was that it was more soulful that way,’ says Marr. ‘You were working with people who you would, and could, sit down and talk to … not to say that it was all one big pyjama party and that we all totally hung out together,

but we were all coming from the same culture.’

‘There is an irony, isn’t there,’ says Travis, ‘that you try and provide a community and a haven and I think they do appreciate that – but their real lives are really insecure – it’s a strange dynamic being a musician.’

Nearly thirty years after the fact, Marr is circumspect. ‘If you look back now and you look at the four or five big influential bands that came out successfully out of that indie scene, and if you lay all the record sleeves out on the floor, you can see who let their work be touched by the hand of the A&R man and therefore became product, took the quid, and those who didn’t, and those who didn’t were The Smiths, New Order and Depeche Mode.’

*

Freidman’s reputation as a bon viveur was well founded. In 2008 he opened New York’s first gastropub, the Spotted Pig. One of his partners and bankers in the venture was Jay-Z.

†

While The Smiths were ambivalent about video, the short film Derek Jarman made for the band, The Queen Is Dead, which included the songs ‘There Is a Light and It Never Goes Out’, ‘Panic’ and ‘The Queen Is Dead’, is one of the most evocative and innovative of the era. The film flickers with a sensual rage, as characters set in landscapes of back streets and empty industrial estates fix their uneasy stares on the camera and are intercut with images of Parliament and Buckingham Palace starting to catch fire. All of Jarman’s work is a far more accurate depiction of the 1980s than those endless clips of yuppies in red braces.

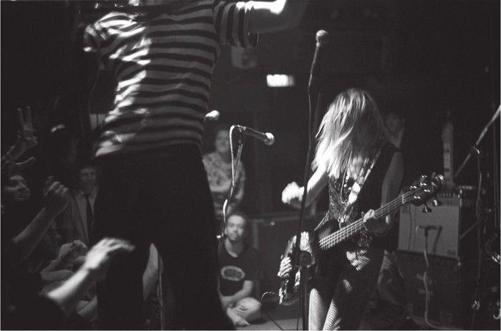

Sonic Youth on stage at the Mean Fiddler, London, 12 July 1987. Paul Smith is seated cross-legged centre, Pat Naylor is standing behind him (

photograph by James Finch used by kind permission of the photographer

)