How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (47 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

A further, fatal, blow was delivered to Rough Trade when a new computer system was installed. For an international distribution company that was still reliant on unreliable and often illegible

handwritten orders and delivery notes, a computer system was doubtless a good idea. Unfortunately the system

Kimpton-Howe

installed at a cost of well over half a million pounds malfunctioned from the beginning. The switch to computer ordering meant that retailers were without several weeks’ worth of new deliveries and had their cash flow put into crisis; the demise of the independent record shop was being accelerated by Rough Trade’s attempt to upgrade the quality of its service.

The board of trustees at Rough Trade, whose exact number and identity has never been agreed upon, decided to call in the administrators and appointed accountancy firm KPMG Peat Marwick to undertake an audit and exert some financial controls over the company. For the first time in its history, Rough Trade’s offices were bustling with men in suits. Travis was now sharing his space with the kind of people whom he had spent his working life trying to avoid. Rough Trade’s layer of middle management had dispersed and it was left for the emergency management committee of Mute, KLF, Beggars and the other labels to reach a settlement with the auditors.

‘It grew too big. Other people were too egotistical, they were too inexperienced,’ says Travis. ‘They didn’t really know how to run that business and yet they didn’t put their hands up and say, “We don’t know what we’re doing any more, we’re out of our depth,” and that’s what went wrong, and they made a lot of fatal errors. And then they all ran away and left me holding the baby to try and deal with it along with these horrendous administrators from the City, which was awful.’

Of all the creditors, Mute was owed the greatest amount and Daniel Miller, Dyer and their head of finance, Duncan Cameron, entered into prolonged negotiations with the auditors on behalf of the emergency committee. ‘Rough Trade Distribution was hugely successful,’ says Miller. ‘The KLF were massive, we’d

just had

Violator

, one of our biggest albums ever, Erasure was huge. In theory things should have been going well. And it all went wrong at that point, endless things, classic NHS things. They spent a fortune on a computer system that didn’t work, everything just went wrong. There were a lot of people who felt very strongly about RTD. And we had to try and fucking rescue the company, partly because of the ethos and partly because loads of labels were owed a fortune by Rough Trade.’

‘We were in for the most money,’ says Dyer. ‘I think it was around a couple of million plus. This was all revealing itself among the panic stations stuff. KLF were in for a million and the guy who worked for KPMG could try and tell everyone what to do. But it’s a very fluid situation, a company in administration rather than liquidation – they were reliant upon our co-operation, they needed all of our co-operation to keep trading through.’

While the tortuous audit of Rough Trade continued to try to differentiate between the companies’ assets and its liabilities, one of its chief creditors, KLF Communications, which had only one artist with a release, The KLF, were attempting to finish recording their next single. In a remarkable demonstration of multitasking, Bill Drummond was dividing his time between attending the emergency committee and finalising plans for ‘Justified and Ancient’. Jimmy Cauty remained in the studio collaborating with Drummond via the phone. ‘Bill And Sally would be there working out how much money we were owed and I’d be in the studio trying to finish the track,’ says Cauty, ‘and trying not to think about the studio bill.’

‘We were all having to put our records out still,’ says Dyer, ‘so in the middle of a meeting we’d say, “You agree to that Bill? KLF represents 13 per cent of the debt, don’t you?” And he’d say, “Yeah, just a minute,” and then he’s on the end of the phone going, “Yeah, bit more bombastic Jimmy, bit more bombastic,”

so he’s having to do a mix-down with Jimmy Cauty who’s in the studio at the other end on the phone. Then he’d ring up Pinewood and would spend a hundred grand on the video. He was hiring the sound stages saying, “No, we don’t need the submarine stage today.” Incredible, visionary behaviour.’

As well as Mute and KLF, the Beggars Group, particularly 4AD, were also owed substantial monies. Halfway through negotiations Big Life and Rhythm King cut their losses and withdrew from the discussion, leaving a core of stalwarts of the independent sector who had started almost simultaneously with Rough Trade. Ivo Watts-Russell had attended a few meetings, but his natural reticence made him uncommunicative. ‘I sat there,’ he says, ‘and didn’t say very much. In fact I don’t think I said anything at all, so Martin Mills went along instead and was incredibly helpful – he was a rock, really.’

‘It was a very painful period, obviously,’ says Mills. ‘We got caught pretty badly in it. I think a Cocteau Twins album had just come out and we hadn’t been paid. Also, the first Charlatans album, which was on Situation Two and was a no. 1 album, was also in a position of having just come out and not been paid for. It was a pretty big surprise to us. It hadn’t really occurred to us that it could happen. To be honest, if we’d been closer to the inside we might have realised where the seeds had been sown.’

While Mute, 4AD, The KLF and a few smaller labels like Fire were in a position to negotiate with KPMG, the remaining smaller labels, the kind that had thrived and been created under Rough Trade’s off-the-street production and manufacture deals, were forced into closure along with Rough Trade. Many of them were bedroom operations with few overheads and several hundred copies of their singles piled up on the shelves in the overspill warehouse in Camley Street, but the dream of starting a label for no other reason than releasing some music that might turn the

heads of John Peel and his audience was over.

‘Mute’s existence wasn’t threatened by it, because we didn’t have a big release out and also we were doing extremely well overseas,’ says Miller. ‘But it was nevertheless a big thing, and it did threaten the existence of a lot of labels. Duncan Cameron did an incredible job fighting for all the labels’ survival. Some people had some kind of insurance, some people didn’t, so in the end a number of labels did go under or just decided to stop.’

Andy Childs had spent an uncomfortable few weeks when he started at Rough Trade. The phone was constantly ringing as smaller labels with no representation at the emergency committee and a never-ending stream of shops, suppliers, courier companies, repro houses – the whole supply chain of Rough Trade’s extended networks – were trying to get an answer about developments at Seven Sisters Road. Their only access to the situation was the weekly music press stories which ran a commentary on the number of job losses and published whatever reassuring but meaningless statements it could produce out of whoever was left in the offices and had the strength to answer the phone.

‘Rough Trade Distribution was incredibly important to a lot of labels and a lot of them went bust,’ says Childs. ‘A lot of people lost money and only the big ones really survived properly, Beggars and Mute and those people. There was a general flow of people all the time, going back and forth. People would leave without you realising – you’d come in one day and there’d be a different set of people, usually wearing suits shaking their heads and looking at figures.’

*

Once the due diligence had been done by KPMG Peat Marwick (whose fees were over £10,000 a week), the one agreed asset that Rough Trade had for sale was The Smiths back catalogue. Travis

had little say in what could happen to the jewel in his label’s crown. The Smiths’ recordings were owned not by Rough Trade Records but by Rough Trade Distribution; as the first band to be signed to Rough Trade on a long-term deal, Travis had had to ask Distribution for the resources to make the band a serious offer. ‘The Smiths were signed to Rough Trade Distribution,’ says Childs, ‘which was one of the reasons why the label was in trouble, because they didn’t own The Smiths. When he wanted to sign The Smiths, Geoff probably didn’t have the money to sign them with the label account so he went to Distribution and got them to sign them, and Distribution needed that money from The Smiths income to try and prop up all the other disasters that were going on. So in the end they sold The Smiths to Warners. It’s hard to say why it did go wrong. You can’t have a big band like that and lose money easily: you’ve got to be doing something really badly wrong.’

Warners, who via Seymour Stein and Sire, had The Smiths licence for the States, were best placed to realise the long-term value of The Smiths and put in a serious bid for their rights. Although the Rough Trade label’s catalogue was seriously diminished without The Smiths, in a moment of great dignity, Travis added the rest of the Rough Trade masters to the asset pile, many of which were later auctioned off by KPMG. In the case of a handful of Rough Trade artists, notably Galaxie 500, the tapes were bought back by the bands themselves. ‘When it all went wrong Geoff was big enough to stand up and say, “I’ll take it on the chin,”’ says Mills, ‘and he threw Rough Trade Records into the pot, which he didn’t have to do. He’d absented himself quite substantially from the runnings of the distribution operation by then.’

Mute, Beggars and a handful of the other minor creditors then set about establishing a new distribution company, one which

would replace Rough Trade on a much smaller, more streamlined scale. With a percentage of the revenue from the distribution fees, they would begin the long process of compensation for their Rough Trade debts. ‘What happened was, we got as many of the best people as we could from Rough Trade,’ says Miller, ‘and started a new company, called RTM. I still believe in the independent sector, that’s where the best stuff comes from, and you’ve got to have a way of servicing that sector as much as you can.’

The ignominy of its ending was an unsatisfying legacy for Rough Trade. In all its different configurations, however naive or successful, it had offered an open door through which people were encouraged to walk and join the experiment. What had started as an idealistic project had ended in the cold market realities of administration, insolvency and a visit from the auditors; it had also left many of the micro-organisations, bands, labels and projects it had unconditionally supported high and dry.

At the start of a new decade, over fifteen years after it had opened as a shop, there were plenty of people in both the majors and independents who saw Rough Trade’s closure as a definitive end to an era and to the experiment. ‘The collapse of Rough Trade felt like some form of rite of passage,’ says John Dyer. ‘You would never get a band to trust to sign to you unless you got paid. I remember Tony Wilson saying one day that the only people who’d ever ripped him off were indie distributors around the world. “So don’t just say that indies are good and majors are bad,” and I repeat that riff to this day; he said, “there are great people at major labels and there are wankers at indies,” and that’s true, it’s completely true.’

It would be some years before Travis resurfaced as a force in the music industry. Only a few of his contemporaries in Collier

Street, and even fewer from Kensington Park Road, would stay the course with him. It is a mark of his passion for music and discovering new ideas – the sine qua non of a truly great A&R person – that he survived the brow-beating and blame-chasing of the collapse of Rough Trade to emerge once more as a highly revered maverick.

‘When it closed, it was a horrible day which I still remember,’ says Robin Hurley. ‘Geoff was in New York to see Dinosaur Jr on the day we found out the UK company was insolvent. We were limping along anyway. In the US there’s a law that says if your parent company is insolvent, then you have to cease to trade, so we had to shut up shop and everyone was let go.’

The next few years were not easy for Travis who, although determined to carry on, would have to regroup in a new set of conditions and in a music environment where the laissez-faire, artist-led ethos of Rough Trade was no longer tenable. ‘It was a horrible dark, dark, time,’ he says. ‘A really dark time and I think I almost had a nervous breakdown.’

Richard Scott, his former partner, conspirator, adversary, idealist and dreamer in the Rough Trade project made one last visit to the company as its winding-up notices were being processed and a skeleton caretaker staff was supervising the final closure. ‘When Rough Trade went belly up, I drove up to the Seven Sisters building, and parked my car in the warehouse. I got out and said, “I’ve come to take the speakers,” and nobody knew who I was. They were the same speakers, a pair of studio monitors. They’d come from the back room at Kensington Park Road. They were the ones that had driven the first sound system in the shop. I just put them into my car and drove off.’

*

Such was the lack of interest in

World of Echo

, that Cerne Canning, who was on the Rough Trade staff at the time, remembers the record being used as a frisbee in the Rough Trade warehouse.

PART THREE

You Are the One to Remember

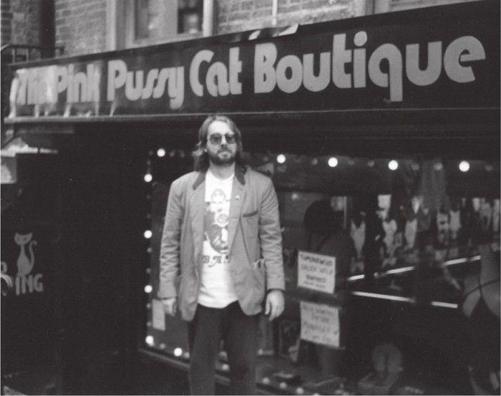

Dave Barker takes a walk on the Lower East Side, New York, 1990 (

David E. Barker archive

)