How to Be Like Mike (13 page)

Read How to Be Like Mike Online

Authors: Pat Williams

These characters became cultural icons because there are pieces of each in all of us, because there is no one who hasn’t failed, who hasn’t felt like everything they tried was colored in futility, that there was nothing to look forward to except continual frustration. But these are also characters born of hope, fueled by the value of persistence.

“He keeps trying, over and over and over,” said Wile E. Coyote creator Chuck Jones. “That trait is possibly the only thing that all creative people have in common. They don’t give up.”

“There is one thing I learned a long time ago,” said

Peanuts

and Charlie Brown creator Charles Schulz. “If you can hang on for a while longer, there is always something bright around the corner. The dark clouds will go away and there will be some sunshine again if you’re able to hold out. I think you just have to wait it out.”

The man who can drive himself further once the effort gets painful, is the man who will win.”

—Roger Bannister

FIRST TO RUN A MILE

IN LESS THAN FOUR MINUTES

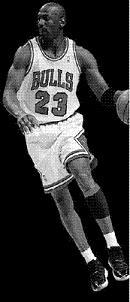

It was no great secret what would happen in the fourth quarter of a taut game in Jordan’s realm. It was as if the rest of the court faded to black and white and Jordan remained, taking the ball, driving to the hoop, getting knocked down hard, drawing a foul, over and over and over again, until it became almost comical. The opposing team could try anything, could knock him down in brutal fashion, and he’d continue to rise and try it again. Eventually, they’d wear down. Jordan wouldn’t. He could be sick. He could be exhausted, clinging to his shorts, tongue draped from his mouth, and he’d keep driving, keep getting battered, keep shooting foul shots into eternity.

Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unre-warded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.

—Calvin Coolidge

“When I was with the Nuggets, we were up on the Bulls in Denver by twenty-six in the fourth quarter,” said former NBA player Danny Schayes. “We hung on to win by three. Michael got fifty-two. He was incredible. We were lucky to hang on. He never quit in the fourth quarter. No lead was safe with Michael in the game.”

“MJwould keep driving to the hole time after time,” said former NBA player Xavier McDaniel. “You hit him and knock him down;most guys would start to pull up and take jump shots. Not MJ. He’d never stop going to the rack, no matter how many times you knocked him down.”

“With Michael Jordan you could never let your guard down,” said former NBA guard Paul Pressey. “He was so relentless you couldn’t rest for a second because he was always on the attack, always dogging you. And he did it on the bench, too. He’d study everything and when he’d get back in the game he’d have picked something up to attack you more.”

Mark Randall, a former Bulls player, recalled:“One year in an exhibition game, we were losing badly late in the game. During a time-out, MJ yelled at all of us ‘Don’t ever think about quitting tonight. If they think you’re weak now, then later in the season they’ll kill you when it counts. ’”

Fight one more round. When your feet are so tired that you have to shuffle back to the center of the ring, fight one more round. When your arms are so tired that you can hardly lift your hands to come on guard, fight one more round. When your nose is bleeding and your eyes are black and you are so tired that you wish your opponent would crack you one on the jaw and put you to sleep, fight one more round—remember that the man who always fights one more round is never whipped.

—James J. Corbett

HEAVYWEIGHT BOXER

My adopted son David spent two weeks in college before deciding it wasn’t for him. The next day, I took him straight to the Marine recruiting station; let’s just say that he enrolled voluntarily, but if he wasn’t going to finish college, he didn’t have a whole lot of choice. He went through twelve weeks of basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, with no contact from the outside world. The next time we saw him was at his graduation ceremony. Afterward, the Marines were released to their parents, who waited out on the tarmac.

When David saw me, he began to cry. He threw his arms around me and buried his head in my shoulder.

“I heard your voice the whole time, Dad,” he said. “I didn’t quit.”

There is obviously a pathway to persistence. It relates heavily to the Jordan we’ve already discussed, to the man who pushed himself harder than anyone in the game, who disciplined himself with almost alarming harshness.

The pathway to persistence lies in self-discipline.

The Soul of an Army

B

eing a professional, is doing all the things you love to do on the days you don’t feel like doing them.

—Julius Erving

I

t was at North Carolina that Jordan first honed his sense of discipline. Here again, it was Dean Smith who influenced him, who led him to the realization that nothing is accomplished without the ability to push through hardships, to deny small yearnings for the sake of the greater goal.

“I believe that the disciplined guy can do anything,” Smith said. “He can choose to stay up late or not. He can choose to smoke ten packs of cigarettes or not. Usually, the people coming into college basketball had to have some discipline, or they wouldn’t be that good. They’ve had to say no a lot of times to other things to go work on their basketball. And players still want to be disciplined. They feel loved when they’re disciplined.”

“One day at practice, Dean Smith read a ‘Thought of the Day’,” said former North Carolina trainer Mark Davis. “The quote was ‘Discipline makes you free. ’ MJ was there. He heard it. I think that quote captures him.”

Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable, procures success to the weak and esteem to all.

—George Washington

One of my all-time favorite movies is

Lean on Me,

a story about principal Joe Clark trying to resurrect an inner-city high school in Newark, New Jersey. Clark, played by Morgan Freeman, utters this classic line:“Discipline is not the enemy of enthusiasm.”

In 1975, Junko Tabei became the first female to climb Mount Everest. After her success she said, “Technique and ability alone do not get you to the top; it is the willpower that is the most important—it rises in your heart.”

There are those moments when no one is watching, those times when work becomes laborious, when we feel as if we’re going to sink underneath our desks, when we wish we could go home and sleep for months at a time. We live large portions of life like this, in that period athletes call The Grind. And I have noticed that this is the period of life in which most people tend to throw up their arms and surrender. But this is when the victorious figures of our society have done the opposite. They’ve developed an immunity to The Grind. “The Grind,” said ex-tennis star Jimmy Connors, “is the stew of talent and determination that keeps certain players hammering on, even when the match score favors the opponent. The Grind is the sweat addiction that pulls some players out of bed in spite of aches and muscle strains. It’s the part of all this I enjoy the most.”

Jordan thrived in The Grind, in those times when his natural instincts wouldn’t have led him to a basketball court, when he had to fight his mind and his body, grit through pain and doubt just to make it onto the court. That ability to persevere, to grind even at his weakest, is a product of strength, of will, of preparation, most of it within the walls of his own psyche. It’s the product of Jordan continually pushing himself to untold limits.

Stacey King, one of Michael’s teammates in Chicago, offers a revealing insight:“MJ’s special strength was his ability to play through pain. He just blocked out the pain of a sprained ankle or foot injury and wouldn’t miss a game. Most guys would be out for two weeks, but not MJ. His focus and mental toughness were awesome. (Allen Iverson shows glimpses of that now, but he’s about the only one like Mike that way. )The result was that MJ forced his teammates to play up to his level because he came to every practice and game ready to go all out. People see the glitz and glamour of MJ’s life, but they didn’t see the hard work, preparation and pain he went through.”

He played in Phoenix with an infected foot. The Suns’ team doctor wanted him to go home. Jordan refused. Instead, he played every night on that road trip.

He played once with a broken cheekbone, with blood leaking into his sinus cavity. He never missed a game. He never even missed a practice. He never used a facemask.

“One day, Michael had back spasms in his lower back so bad, we had to carry him off the bus,” said Phil Jackson. “He got forty that night.”

The Bulls’ team doctor, John Hefferon, would often see Jordan’s father, and James Jordan would ask how his son was feeling, and Hefferon would say he wasn’t feeling well, that the flu was coming on, that his stomach was upset. “That mean’s Michael’s going to have a great game tonight,” James Jordan would say.

And most of the time, he was right.

This story comes from a man named Marty Dim. He and his fifteen-year-old son were playing golf at Briarwood Country Club in Chicago one afternoon, and when they reached the fourth tee, they caught up with Michael Jordan, who invited them to play the rest of the course with him. Dim’s son was so nervous he could barely speak.

Do something every day that you don’t want to do. This is the golden rule for acquiring the habit of doing your duty without pain.

—Mark Twain

On the fifth hole, Jordan hit his drive into a bush. He hacked out, emerging with torn clothes and scratches on his arm, and made par.

On the sixth green, Dim’s son was still a wreck. He lagged behind. He saw that the others were finished playing and told them to go ahead.

Jordan was on the far side of the green. He charged across, stopped a few inches from the kid’s face, and said, “Are you quitting on me?” He repeated it, over and over. “Are you quitting on me? Are you quitting on me?”

In the 1989 Chicago-Detroit play-offs, I saw a play that I think was the defining moment of Michael’s career. He drove down the middle and Rick Mahorn and Bill Laimbeer hammered him to the ground. Hard. He got up limping. The next game, he was still banged up. That was Michael tasting the NBA at its most bitter. After that, he realized he had to take over.

—Mike Abdenour

TRAINER, DETROIT PISTONS

“Michael,” Marty Dim said, “just would not let him give up.”

Which leads us back to Game Five of those 1997 NBA Finals, Jordan fighting a vengeful flu virus and taking intravenous fluids, his pallor so gray that one sportswriter said he literally “shook with fear” for him. And when Mike Wise of the

New York Times

surveyed Jordan’s gaunt figure late in the game, he leaned over press row and muttered to Michael Wilbon of the

Washington Post,

“It’s over.” Wise did what many print reporters fighting deadline had done. He wrote his story as if Utah had won the game. And while he was writing, Jordan—as if once again summoned by adversity—began to alter the course of Wise’s story single-handedly, to scrape through the debilitation and win this game virtually by himself. And to demonstrate, Wise said, “what perseverance really is.”

But this perseverance was not merely a lone act of will. It was a build-up, the summation of years of training, of Jordan sharpening his own resolution. And eventually developing an impenetrable wall of discipline.

Once you learn to quit it becomes a habit.

—Vince Lombardi

“His body wouldn’t let him down at the moment of truth because of the way he had trained it,” said

Chicago Tribune

columnist Bernie Lincicome. “It didn’t know how to quit.”

JORDAN ON RESPONSIBILITY:

T

he he game is my wife. It demands loyalty and responsibility, and it gives me back fulfillment and peace.

T

he price of greatness is responsibility.

—Winston Churchill

I

am what some would call an old-fashioned father. To my children, this means I’m mired in a black-and-white pre–

Leave It to

I

Beaver

utopia, in a mentality that is so removed from their own consciousness, they have trouble believing the human race existed back then. Mostly, my children think that I belong in the 1940s. Sometimes, if they are feeling generous, they will inform me that I have advanced to the 1950s, but still they consider me marooned in an Eisenhower-era dream world.

I also know that most of the time, my children are correct. Take the trend of body piercing and permanent tattoos, something that I encounter every day as an NBA executive. Regarding tattoos, this is my rule with my children:As long as they are living under my roof, eating meals and wearing clothes that are paid for with my salary, they will get no tattoos, and they will not pierce anything that could not be exposed in church.