How to Be Like Mike (21 page)

Read How to Be Like Mike Online

Authors: Pat Williams

There are three lessons to be taken from this. The first is that politeness can be a disarming strategy when competing. The second is that the politeness of others can be a disarming strategy when competing. And the third is that there is a time, in the midst of competition, to let politeness fade for the moment.

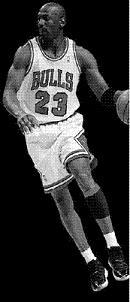

It was difficult not to place Jordan on some higher plane. Rarely, if ever, has sports been blessed with such a pure competitor, a man whose lone goal was victory by whatever means necessary. He was intimidating, he was fearless, he was driven and the legacy of his competitive nature is like none to come along in generations.

It continues to trickle down in the residue of memories like those of veteran pro Larry Robinson, who on the first night of his rookie season in Washington in 1991 was assigned to guard Jordan. Jordan had powdered resin on his hands, and as he touched fists with his opponents, bits of powder burst from his hand. The Bullets won the opening tap, and Jordan backpedaled to play defense. What Robinson didn’t realize was that Jordan kept powder inside his fists as well. Michael raised his arms, opened his hands, and the powder sprinkled down upon him like fairy dust.

JORDAN ON TEAMWORK:

T

here are plenty of teams in every sport that have great players and will never win titles. Most times, these players aren’t willing to sacrifice for the greater good of the team. The funny thing is, in the end, their unwillingness to sacrifice only makes individual goals more difficult to achieve.

A great player can only do so much on his own, no matter how breathtaking his one-on-one moves. If he is out of sync psychologically with everyone else, the team will never achieve the harmony needed to win.

—Phil Jackson

G

rant Hill held up one of his hands. He stretched five rangy fingers at me, spreading them as far apart as they would go.

“These,” he said, “are the five members of a basketball team.”

We were sitting in the locker room in Orlando. It was Hill’s first year with the Magic after six years with the Detroit Pistons, but he was reaching back further, to his years at Duke, to a speech that his coach, Mike Krzyzewski, used to give.

Hill waggled his fingers. “These,” he said, “do not become very effective until they are joined together tightly.” He balled his hand into a fist. “This,” he said, “can cause much more damage than five fingers sticking in different directions.”

Hill relaxed his hand, so that the fist became a jagged creature with a couple of fingers splayed apart.

“If one or two stick out,” he said, “that’s not a very effective fist.”

That, Hill said, became the rallying cry for a Duke team that won NCAA titles in 1991 and 1992. It is a vivid illustration of a principle that interlopes on the worlds of both sports and business: the notion of teamwork.

It was something that Michael Jordan did not accept when he entered the NBA. At first, he tried bullying his way to a championship. He had the idea that he could hoist an entire team on his shoulders and lead it through the play-offs. In retrospect, it’s easy to understand why he felt this way. Those early teams Jordan played on in Chicago were not exactly blessed with grade-A talent. It was his show, and nobody else’s. He had no one to rely on, no one to depend upon besides himself. But when Jordan scored sixty-three against the Celtics in the 1986 play-offs, his team still lost. And the Celtics, with Larry Bird, with Kevin McHale, with Robert Parish and Dennis Johnson and Danny Ainge, did not lose.

In 1983, Michael was kind of full of himself and dogging it at practice. Dean Smith had a rule that if you dogged it, the whole team had to run extra. So Dean stopped practice, put a chair in the middle of the floor, and told Michael to sit and watch while the rest of the team ran. I think that was a defining moment for Michael.

—David Chadwick

PASTOR AND AUTHOR

By the end of his career, Jordan had developed a complex symbiosis with his teammates. Together they earned those six championship rings.

You want your company to run well? Here’s an ironclad rule: Get everyone on the same team. Get everyone working for the same team. Get everyone working for the same goal; get them to win or lose together.

—Gordon Bethune

CEO

OF

C

ONTINENTAL

A

IRLINES

If there is one concept that I have studied more than others in my years as an NBA executive, it’s that of teamwork. I have presided over terrible teams (we won’t get into details) and championship teams (I won’t brag, though I certainly could, if you ask) and I have isolated those elements that make up the difference. Call it chemistry or bonding or mutual acceptance or any of the above. The absolute truth is that sports franchises fail— just as corporations fail— without teamwork.

Without everybody embracing what we want to do, we haven’t got a prayer.

—Jack Welch

CEO

OF

G

ENERAL

E

LECTRIC

No surprise, then, that teamwork has become one of those buzzwords for corporate America. A great many of my public-speaking clients ask me to address this topic, whether to a grand ballroom of

Fortune 500

CEOs or a banquet hall filled with small-business owners. They’re all curious about the same thing: is what happens in sports transferable to the business world?

Business—and this means not just the business of commerce, but the business of education, the business of government, the business of medicine, is a team activity. Always, it takes a team to win.

—Andrew Grove

CEO OF

I

NTEL

The obvious answer is: Yes. Of course. The less obvious question is:

How

is it transferable to the business world?

I spent a few years looking into this. I even wrote a book about it,

The Magic of Teamwork.

What I attempted to discern were the defining characteristics of great teams. What follows are my eight primary findings, dovetailed to the experience of Michael Jordan.

When you don’t take care of the team first, the baseball gods won’t let you get away with it.

—Todd Hundley

MAJOR-LEAGUE CATCHER

1. Talent

You can take an old mule and run him, feed him, train him and get him in the best shape of his life, but you ain’t gonna win the Kentucky Derby.

—P

EPPER

M

ARTIN

former major-league baseball star

I owe this one to Jack Ramsay, the longtime NBA coach and broadcaster, who looked at my list of great team characteristics and told me—as B. J. Armstrong had once told me about my Jordan outline—that I’d forgotten the most important thing.

“Can’t have a great team,” he said, “without great talent.”

Pretty simple thought. But one of those things we have a tendency to forget. We think we can piece together our organizations with people of patchwork abilities, that we can stretch them to their absolute capacities and it will be enough.

And sometimes it may be.

But most of the time, it probably won’t be.

You will notice that even the greatest coaches don’t win without talent. When Phil Jackson first became coach of the Bulls, the franchise was just beginning to refine its talent level. When Jackson surrounded Jordan with a higher caliber of player, and with role players who completed their tasks without fail, the Bulls began to form a dynastic core.

“If you have talented players, you can win,” Jackson said. “If you know what to do as a coach, you can bring out the best in talented players. To go off and coach a team that’s going to win fifteen games, I can’t.”

It matters, of course, that you are able to recognize talent (“The ability to discover ability in others,” said author Elbert Hubbard, “is the true test” ), and to choose coachable people, those who are willing to accept the demands of others, who are dedicated to goals larger than themselves.

It also matters that you help talent settle into its proper place. The key to handling talent, says sports executive Mark McCormack, is this: “Employ it properly, then leave it alone.”

“Find some people who are ‘comers, ’” said Dallas businessman John Stemmons. “People who are going to be achievers in their own field and people you can trust. Then grow old together.” NBA player Juwann Howard asks, “You know how good teams win? By staying together.”

Talent alone is not enough. They used to tell me you have to use your five best players, but I’ve found that you win with the five who fit together best.

—Red Auerbach

And this is what Bulls general manager Jerry Krause did. He drafted Horace Grant and Scottie Pippen in the spring of 1987, then hired Jackson as an assistant coach (under Doug Collins) that fall. He recruited the best talent he could find. He set the pieces into place. It was up to Jackson to provide for the development of his young players, like Pippen, a raw talent from Central Arkansas. Jackson taught him to find his shot and to harness his athleticism, to develop his abilities in four crucial dimensions: physical strength and skill, plus emotional and spiritual well-being.

So the talent was acquired, and the talent was harnessed. It was up to Jordan to provide the final element: cohesion.

“Michael had four qualities,” said NBA scout Yvan Kelly. “Number one—superior athletic ability; number two—superior skills; number three—mental toughness; and number four—synthesizing these elements into team play. You will find players with as much talent and skills, but they just can’t pull it together.”

2. Leadership

There are many elements to a campaign. Leadership is number one. Everything else is number two.

—B

ERTOLT

B

RECHT

business leader

Here is another word that has infused itself into nearly every facet of the corporate lexicon—leadership. In fact, barely a day passes that my mailbox is not stuffed with an invitation to a seminar or conference on leadership. One of these took me to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where the Magic leadership group spent two days going through team-building exercises, including an afternoon in the woods doing team adventure drills. Our final activity of the day: climbing a twenty-five-foot wooden wall.

The rules were that two people could help from a platform stationed at the top, but no one else. This meant the first and last people had to get up without help.

There were eighteen of us. It took thirty minutes. When we were finished, we celebrated as if we’d just won an NBA championship.

Of course, it didn’t hurt having our team vice president, Julius Erving, climb up that wall in two giant strides to complete the drill.

Leadership is getting players to believe in you.

—Larry Bird

In the midst of the 1992–93 season, the Bulls were struggling through a long road trip and trailing Utah by seventeen points in the waning seconds of the third quarter when Jordan hit a half-court shot to cut the lead to fourteen. Suddenly, something triggered. “ Michael became so driven, so focused, so committed to his teammates,” said former Bull Trent Tucker.

In the fourth quarter, Jordan scored twenty-two points. Chicago won the game.

One night we were out of sync. Nothing was working for us and I was mad. I said to Isiah Thomas during a time-out, “What’s your greatest asset?” “Leadership,” he replied. “Then lead,” I yelled.

We won the game.

—Chuck Daly

FORMER COACH,

D

ETROIT

P

ISTONS

So important is this concept that I’ve dedicated the entire next chapter (chapter 9) to it. But the obvious relationship between leadership and teamwork is this:

Every team needs its leaders.

There are certainly varied types of leaders, some who lead through action and some who lead more vocally.

Michael Jordan, at times, could be both.

“MJ had an ability to orchestrate a game,” said NBA assistant coach Jim Eyen. “He was a maestro. He couldn’t do it by himself, so he’d delegate, but he was always in control of the baton. He learned how to make other players feel part of what he was doing.”

“During the 1991 finals,” said former Bulls’ assistant John Bach, “MJ got up and told the team, ‘Look, we’re going to the top. You’re either with me or you’re not. ’”

You have achieved excellence as a leader when people will follow you anywhere, if only out of curiosity.

—General Colin Powell

The night before training camp was due to begin, Phil Jackson would ask around the room, soliciting from each player his individual goals. Back came the answers: points, rebounds, assists, an All-Star game appearance. Jordan would always go last. He would always say the same thing.