How to Break a Terrorist

Read How to Break a Terrorist Online

Authors: Matthew Alexander

The views presented in this book are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. Government agency.

Free Press

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2008 by Matthew Alexander

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Sources for photo insert:

Coalition Forces: Figs. 1, 3, 4, 5 6, 8

Hameed Rasheed/Associated Press: Fig. 2

Department of Defense: Figs. 7, 10

Karim Kadmin/Associated Press: Fig. 9

Matthew Alexander: Figs. 11, 12

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of

Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alexander, Matthew

How to Break a Terrorist: The U.S. interrogators who used brains, not brutality, to take down the deadliest man in Iraq / Matthew Alexander with John R. Bruning.

p. cm.

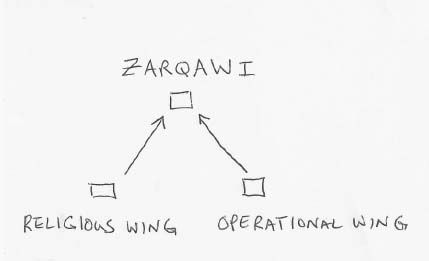

1. Terrorists. 2. Zarqawi, Abu Mus’ab, 1966–2006.

3. Qaida (Organization) 4. Alexander, Matthew.

5. Military interrogation. I. Bruning, John R. II. Title.

HV6433.M52A54 2008 956.7044'3—dc22

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-7340-1

ISBN-10: 1-4165-7340-2

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For the American soldiers and Iraqi civilians

who have died in this war.

IT WOULD BE

impossible to recollect every word of every interrogation that I conducted or monitored in Iraq, but I’ve detailed these conversations as accurately as I could. I am writing under a pseudonym, and I have deliberately changed names and some operational details throughout to protect U.S. troops, ongoing missions, and the families of detainees from Al Qaida reprisals. This material was submitted to the Department of Defense for prepublication review and the blacked out material reflects deletions made by the DoD.

by Mark Bowden

I

GREW INTRIGUED BY

the subject of interrogation in 2001, not long after the September 11 attacks, because to combat small cells of terror-bent fanatics, the essential military tool would be not weaponry but knowledge. How do you obtain information about a secretive enemy? There would, of course, be spying, both electronic and human. America is perhaps the most capable nation in the world at the former and would have to get better fast at the latter. The third tool, potentially the most useful and problematic, would be interrogation.

How do you get a captive to reveal critical, timely intelligence? I wrote about interrogation theory for

The Atlantic

in 2002 in an article called “The Dark Art of Interrogation,” which predated the revelations of abuses at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. In the years since, the subject matter has become predictably politically charged and highly controversial, with liberals viewing harsher tactics as a sign of moral and legal degeneration, and conservatives regarding attitudes toward coercion as a litmus test of one’s seriousness about the war on “terror.”

When I first met Matthew in 2007, it was a chance to learn exactly how our military was conducting high-level interrogations five years on. I was surprised (although I should not have been) to learn that a cadre of professional interrogators, or ’gators, had taken root inside the military: young men and women, some in uniform, others private contractors, who had years of hands-on experience interrogating prisoners in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. It was heartening to learn from Matthew that the army had outgrown some of the earlier cruder methods of questioning. The quickest way to get most (but not all) captives talking is to be nice to them.

But what does it mean to be “nice” to a subject under interrogation? As Matthew’s firsthand story of the intelligence operation that located and ultimately killed Abu Musab al Zarqawi illustrates, it often means one thing to the subject and another to the interrogator. It means, ideally, getting to know the subject better than he knows himself and then manipulating him by role-playing, flattering, misleading, and nudging his or her perception of the truth slightly off center. The goal is to turn the subject around so that he begins to see strong logic and even wisdom in acting against his own comrades and cause.

The greater part of the noise in media and politics over interrogation concerns the use of physical coercion, which is relevant to only a tiny fraction of the cases handled by military intelligence. The real work, as this book illustrates, can be far more challenging, complex, and interesting. The work could not be more important. Long after U.S. troops leave Iraq and even Afghanistan, the work of defeating Islamic fanatics will go on worldwide. We need more talented ’gators

like Matthew, ideally ones with broad knowledge and experience in the parts of the world where they work, with fluency in local languages and dialects, and with a subtle understanding of what makes people tick.

Because if you know that, you also know what makes them talk.

PROLOGUE

By God, your dreams will be defeated by our blood and by our bodies. What is coming is even worse.

—A

BU

M

USAB AL

Z

ARQAWI

MARCH,

2006

T

HERE’S A JOKE

interrogators like to tell: “What’s the difference between a ’gator and a used car salesman?” Answer: “A ’gator has to abide by the Geneva Conventions.”

We ’gators don’t hawk Chevys; we sell hope to prisoners and find targets for shooters. Today, my group of ’gators arrives in Iraq at a time when our country is searching for a better way to conduct sales.

After 9/11, military interrogators focused on two techniques: fear and control. The Army trained their ’gators to confront and dominate prisoners. This led down the disastrous path to the Abu Ghraib scandal. At Guantánamo Bay, the early interrogators not only abused the detainees, they tried to belittle their religious beliefs. I’d heard stories from a friend who had been there that some of the ’gators even tried to convert prisoners to Christianity.

These approaches rarely yielded results. When the media

got wind of what those ’gators were doing, our disgrace was detailed on every news broadcast and front page from New York to Islamabad.

Things are about to change. Traveling inside the bowels of an air force C-130 transport, my group is among the first to bring a new approach to interrogating detainees. Respect, rapport, hope, cunning, and deception are our tools. The old ones—fear and control—are as obsolete as the buggy whip. Unfortunately, not everyone embraces change.

The C-130 sweeps low over mile after mile of nothingness. Sand dunes, flats, red-orange to the horizon are all I can see through my porthole window in the rear of our four-engine ride. It is as desolate as it was in biblical times. Two millenia later, little has changed but the methods with which we kill.

“Never thought I’d be back here again,” I remark to my seatmate, Ann. She’s a noncommissioned officer (NCO) in her early thirties, a tough competitor and an athlete on the air force volleyball team.

She passes me a handful of M&M’s. We’ve been swapping snacks all through the flight. “When were you here?” she asks, peering out at the desertscape below. Her long blonde hair peeks out from under her Kevlar helmet.

“Three years ago. April of o-three,” I reply.

That was a wild ride. I’d been stationed in Saudi Arabia as a counterintelligence agent. A one-day assignment had sent me north to Baghdad, shivering in the back of another C-130 Hercules.

Below us today the southern Iraqi desert looks calm. Nothing moves; the small towns we pass over appear empty. In 2003 it was a different story. We flew in at night, and I

watched the remnants of the war go by from 200 feet, a set of night-vision goggles strapped to my head. Tracer bullets and triple A (antiaircraft artillery) arced out of the dark ground past our aircraft, our pilot banking the Herc hard to avoid the barrages. Most of the way north, the night was laced with fire. Yet when we landed at Baghdad International, we found the place eerie and quiet. Burned-out tanks and armored vehicles lay broken around the perimeter. I later found out they’d been destroyed by marauding A-10 Warthogs.

On this return flight, we face no opposition. The pilots fly low and smooth. The cargo section of these C-130’s is always cold. I pop the M&M’s into my mouth and fold my arms across my chest. The engines beat a steady cadence as the C-130 shivers and bucks. Ann puts her iPod’s buds in her ears and closes her eyes. Next to her, I start to doze.

An hour later, I wake up. A quick check out of the porthole reveals the sprawl of Baghdad below. We cross the Tigris River, and I see one of Saddam’s former palaces that I’d seen in ’03.

“We’re getting close,” I say to Ann.

She removes her earbuds.

“What?” she asks.

Mike, another agent in my group, leans in from across the aisle to join our conversation. He offers me beef jerky, and I take a piece.

“We’re getting close,” I repeat myself.

We reach our destination, a base north of Baghdad. The C-130 swings into the pattern and within minutes, the pilots paint the big transport onto the runway. We taxi for a little while, then swing into a parking space. The pilots cut the engines. The ramp behind us drops, and I see several en

listed men step inside the bird to grab our bags. Each of us brought five duffels plus our gun cases. When we walk, we look like two-legged baggage carts.

“Welcome to the war,” somebody says behind me.

After hours of those big turboprops churning away, all is quiet. We descend from the side door just aft of the cockpit. As we hit the tarmac, a bus drives up. A female civilian contractor jumps out and says, “Okay, load up!”

Just as I find a seat on the bus I hear a dull thump, like somebody’s just slammed a door in a nearby building—except there aren’t any nearby buildings.

A siren starts to wail.

“Oh my God!” screams our driver. “Mortars!”

She stands up from behind the wheel and dives for the nearly closed door, where she promptly gets stuck. Half-in, half-out of the bus she screams, “Mortars! Mortars!”

We look on with wry smiles.

Another dull thud echoes in the distance. The driver flies into a panic. “Get to the bunkers now! Bunkers! Move!” She finally extricates herself from the door and I see her running at high speed down the tarmac.

“Shall we?” I ask Ann.

“Better than waiting for her to come back.”

We get off the bus and lope after our driver. We watch her head into a long concrete shelter and we follow and duck inside behind her. It is pitch black.

Another thump. This one seems closer. The ground shakes a little.

It is very dark in here. The bunker is more like a long, U-shaped tunnel. I can’t help but think about bugs and spiders. This would be their Graceland.

“Watch out for camel spiders,” I say to Ann. She’s still next to me.

“What’s a camel spider?” she asks.

“A big, aggressive desert spider,” says a nearby voice. I can’t see who said that, but I recognize the voice. It is Mike, our Cajun. Back home he’s a lawyer and a former police sniper. He’s a fit thirty-year-old civilian agent obsessed with tactical gear.

“How big?” Ann asks dubiously. She’s not sure if we’re pulling her leg. We’re not.

“About as big as your hand,” I say.

“I hear they can jump three feet high,” says Steve. He’s a thirty-year-old NCO and another agent in our group of air force investigators-turned-interrogators. This tall, buzz-cut adrenaline junkie from the Midwest likes racing funny cars in his spare time. In the States, his cockiness was suspect. Out here, I wonder if it won’t be exactly what we need.

“Seriously?” Ann asks.

Thump!

The bunker shivers. Another mortar has landed. This one even closer.

“I’m still more worried about the spiders,” Mike says.

I have visions of a camel spider scuttling across my boot. I look down, but it’s so dark that I can’t even see my feet.

The all-clear signal sounds. We file out of the bunker and make our way back to the bus. The driver tails us, looking haggard and embarrassed. Her panic attack cost her whatever respect we could have for her. We climb aboard her bus and she takes us to our next stop.

We “inprocess,” waiting in line for the admin types to stamp our paperwork. We have no idea what’s taking them

so long. Hurry up. Wait. Hurry up. Wait. It’s the rhythm of the military.

Steve finishes first and walks over to us. “Hey, one of the admin guys just told me a mortar round landed right around the corner and killed a soldier.”

The news is like cold water. Any thought of complaining about the wait dies on our tongues. We’d been cavalier about the attack. Now it seems real.

A half hour passes before we are processed. Our driver shows up with the first sergeant and shuttles us across the base to the Special Forces compound where we’ll stay until we accomplish our mission (whatever that is).

When I went home in June, 2003, I thought the war was over—mission accomplished—but it had just changed form. We’ve arrived in Iraq near the war’s third anniversary. The army, severely stretched between two wars and short of personnel, has reached out to the other services for help. Our small group was handpicked by the air force to go to Iraq as interrogators to assist our brothers in green. We volunteered not knowing what we’d be doing or where. Some of us thought we’d go to Afghanistan, perhaps joining the hunt for Osama bin Laden. Only at the last minute before we left the States did we find out where we were going. We still don’t know our mission, but we’ve been told it has the highest priority.

We’re all special agents and experienced criminal investigators for the air force. One of us is a civilian agent and the rest of us are military. I’m the only officer. Ever since the Abu Ghraib fiasco, the army has struggled in searching for new ways to extract information from detainees. We offer an alternative approach. In the weeks to come, we’ll try to prove

our new techniques work, but if we cross the wrong people, we’ll be sent home. They told us that much before we left for the sandbox.

Later that night, after stashing our bags in our trailer homes, we sit in the interrogation unit’s briefing room down the hall from the commander’s office.

My agents are called one by one into the commander’s office for an evaluation. All of them pass. Finally, a tall, blackhaired Asian-American man with a bushy black beard steps into the briefing room. “Matthew?” he says to me.

I step forward. He regards me and says, “I’m David, the senior interrogator.” He leads me to the commander’s office and follows me inside.

“Have a seat,” David says.

I look around. There’s only one free chair, a plush, overstuffed leather number next to one of the desks, so I settle into it.

The office is cramped, made even more claustrophobic by two large desks squatting in opposite corners. Behind one is a gruff-looking sergeant major. David sits next to the door. A third man watches me intently from the far corner, and the interrogation unit commander, Roger, sits behind a desk to my right.

Everyone else sitting in the room is in ergonomic hell. I feel uneasy as I take the best seat in the house. Roger explains to me that this is an informal board designed to make sure we’d be a good fit for the interrogation unit. “We’re going to ask you some questions.”

I struggle to sit up. The chair has me in a comfy grip. If

I’m about to be grilled, this is the last chair I want to be in. I finally have to sit forward, back rigid, to find a position that doesn’t make me look like an overrelaxed flake.

“Look,” Roger says, “We’re happy to have you here.”

“Glad to be here.”

“Okay, let’s get started. David, do you want to go first?”

“Sure,” he says. He has dark rings under both eyes.

“Tell me, what countries border Iraq?” David asks.

“Turkey to the north. Iran to the east, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait to the south, Jordan and Syria to the west.” I answer. My mind races. Did I miss anything between Syria and Turkey?

“Okay. What’s the difference between Shia and Sunni?”

That’s an easy one. “It goes back to the schism in Islam caused by the death of Muhammad. Sunnis believe that the legitimate successor was Muhammad’s closest disciple, Abu Bakr. Shia believe the succession should have been passed through his cousin Ali, who was also his daughter Fatima’s husband. The Shia lost, and Abu Bakr retained leadership until he died.”

David, thinking I’m finished, starts to ask something else. Before he can, I continue, “When Abu Bakr died, the Shia tried to recapture the leadership of Islam, but Ali’s son Hussein was murdered outside Karbala, and the Sunnis have held the balance of power ever since.”

“What the fuck makes you think you can do this job?” It is the sergeant major.

“I’m a criminal investigator and I interrogated on the criminal side. Plus I’ve worked with Saudis so I understand the culture.”

He doesn’t look mollified. “You’re a major, right?” he almost sneers when he says my rank.

“Yes.”

“Around here, there is no rank. We are on a first-name basis. If some young sergeant ends up giving you orders, are you going to have a hard fucking time with that?”

“I never confuse competence with rank,” I reply.

“Fuckin’ A,” the sergeant major says.

The man in the far corner steps up to the plate. “I’m Doctor Brady. I want to know if you consider yourself bright enough for this job. You’re going to be interrogating Al Qaida leaders and men much older than you. What makes you think you can outsmart them?”

“I don’t have to outsmart them,” I say. “

We’ll

have to outsmart them. I know there’ll be a team of analysts supporting me.”

We’ve come full circle. Roger takes the stage and asks, “If you saw somebody, say an interpreter, threatening a detainee, what would you do?”

“I’d make him stop.”

“What if you only suspect he’s threatening the detainee in Arabic and it’s helping your interrogation?”

“I’d pull him aside and ask him what’s going on. If he didn’t stop, I’d bring it up with you.”

“How do you feel about waterboarding, or other enhanced interrogation techniques?”

Ah, the heart of the matter. Ever since Abu Ghraib everyone in the interrogation business has been on edge. Careers are at stake. Jail time is at stake.

“I’m opposed to enhanced techniques. They’re against

Geneva Conventions and, ultimately, they do more harm than good. Besides we don’t need them.”

“What do you mean?”

“A good interrogator can get the information he needs in more subtle ways,” I reply.

“Okay,” Roger says dismissively, “Wait outside. We need to talk.”

Ten minutes later, I’m called back in. Roger smiles and shakes my hand. “Welcome aboard. Get ready because everything will come at you fast. Rule number one: we have a no-tolerance policy for violations of Geneva Conventions. You’ll sit in on three interrogations to see how we do things, then you’ll be on your own.”

David adds, “By the way, do you have any leadership experience?”

“That’s pretty much what I do,” I reply.

“Good,” Roger says. “In three weeks, we’re going to need a new senior interrogator. You’re it.”

Laughter erupts around the room. Apparently, this is a job nobody wants. Looking at David, I think I can understand why.