How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

Read How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself Online

Authors: Robert Paul Smith

BOOK: How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

8.3Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

For Nathalie,

who ate my spinach

who ate my spinach

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

So It Doesn't Whistle

Â

The Journey

Â

Because of My Love

Â

The Time and the Place

Â

“Where Did You Go?” “Out.” “What Did You Do?” “Nothing.”

Â

Translations from the English

Â

The Tender Trap, a play, with Max Shulman

INTRODUCTION

Nothing Doing

I

don't know about you, but I wasted all but about fifteen minutes of my childhood. Those fifteen minutes were spent on a beach in Cornwall busting a nodule of quartz out of a fist-sized chunk of flint; thirty years later, I still have it somewhere in my office, in an old coffee can. Everything else I made during those yearsâthe swords nailed together from pickets, the forest forts that defended nothing from nobody, the poorly assembled Revell model cars with Testors paint smeared lazily on them, the Sherman tanks drawn in near-medieval 2-D perspectiveâthey're all gone now.

don't know about you, but I wasted all but about fifteen minutes of my childhood. Those fifteen minutes were spent on a beach in Cornwall busting a nodule of quartz out of a fist-sized chunk of flint; thirty years later, I still have it somewhere in my office, in an old coffee can. Everything else I made during those yearsâthe swords nailed together from pickets, the forest forts that defended nothing from nobody, the poorly assembled Revell model cars with Testors paint smeared lazily on them, the Sherman tanks drawn in near-medieval 2-D perspectiveâthey're all gone now.

Come to think of it, I haven't used the piece of quartz for much either.

But if I want reminding of where the rest of that time went, I have this book. A step-by-step guide to grinding oyster shells against the front stoop for no reason, to turning buttons and string into buzz saws that won't cut anything, and to making paper boomerangs that don't come back,

How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

is about what you do when you're a kid and have neither money nor anyone paying much attention to you, and where your one guiding principle is that you avoid grown-ups and don't ask for help.

How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

is about what you do when you're a kid and have neither money nor anyone paying much attention to you, and where your one guiding principle is that you avoid grown-ups and don't ask for help.

“Objects made of wood by children,” Smith once estimated, “. . . will assay ten percent wood, ninety percent nails.” And if his book's title also works on the same principle of youthful overengineering, it's because a belief in

efficiency

and

quality construction

is anathema to childhood. Waste rulesâand what Smith knows is that if youth is wasted on the young, it's because an adult would not waste it, and in so doing make it

not

youth.

efficiency

and

quality construction

is anathema to childhood. Waste rulesâand what Smith knows is that if youth is wasted on the young, it's because an adult would not waste it, and in so doing make it

not

youth.

“These days,” he writes, “you see a kid lying on his back and looking blank and you begin to wonder what's wrong with him. There's nothing wrong with him, except he's thinking . . . He is trying to arrive at some conclusion about his thumb.”

So why not carve monkeys out of peach pits? Why not build a tank out of spools and rubber bands, or a paddle-boat out of cigar boxes? Why not make pussy-willow cats up on the fence?

“If things were as they should be, another kid would be telling you how to do this,” Smith admits. But Smith was just about the best guide America had to precious arcana like making a game of “killers” out of the horse chestnuts in your backyard. If Jean Shepherd had written

The Dangerous Book for Boys

instead of

A Christmas Story

, this book would be it. And like Shepherd, Smith had a history in broadcasting, one that began in Manhattan in the late 1930s as a radio writer at CBS. “This paid the rent,” he recalled, “while I wrote four novels which did not.” After penning bohemian novels about Greenwich Village, and cowriting a play that improbably went on to star Frank Sinatra in the movie version, it was marriage and fatherhood that inspired Smith's meditation upon the lore of his childhood. The illustrations by his wife, Elinorâan accomplished author herselfâmakes for a book truly created by the Smith household. It seems fitting that he later wrote a book about “household possessions they don't make anymore”âold cast-offs like carpet beaters, wooden iceboxes, and hat stands. After all, every kid also wonders about the junk in the attic,

and Smith always remembered what it was like to be a kid.

The Dangerous Book for Boys

instead of

A Christmas Story

, this book would be it. And like Shepherd, Smith had a history in broadcasting, one that began in Manhattan in the late 1930s as a radio writer at CBS. “This paid the rent,” he recalled, “while I wrote four novels which did not.” After penning bohemian novels about Greenwich Village, and cowriting a play that improbably went on to star Frank Sinatra in the movie version, it was marriage and fatherhood that inspired Smith's meditation upon the lore of his childhood. The illustrations by his wife, Elinorâan accomplished author herselfâmakes for a book truly created by the Smith household. It seems fitting that he later wrote a book about “household possessions they don't make anymore”âold cast-offs like carpet beaters, wooden iceboxes, and hat stands. After all, every kid also wonders about the junk in the attic,

and Smith always remembered what it was like to be a kid.

That's why

How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

remains timeless. Toys are louder and brighter nowâand a good deal safer than Smith's old games of mumbly-pegâbut kids still do nothing the same way. They pick up the random and discarded object of adult life, or the natural debris that no one with a job or a schedule or

things to do

even notices anyway. Kids will find this stuff, examine it, flip it upside down, throw it, break it, and simply stare at it. Kids will do nothing with nobody all alone by themselves. And you get a sense, after Smith's magisterial symposium on making helicopters out of rubber bands and chicken bones, that there is something more at stake in all this.

How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

remains timeless. Toys are louder and brighter nowâand a good deal safer than Smith's old games of mumbly-pegâbut kids still do nothing the same way. They pick up the random and discarded object of adult life, or the natural debris that no one with a job or a schedule or

things to do

even notices anyway. Kids will find this stuff, examine it, flip it upside down, throw it, break it, and simply stare at it. Kids will do nothing with nobody all alone by themselves. And you get a sense, after Smith's magisterial symposium on making helicopters out of rubber bands and chicken bones, that there is something more at stake in all this.

“I understand some people get worried about kids who spend a lot of time alone,” Smith muses in his closing lines, “. . . but I worry about something else even more; about kids who don't know how to spend any time all alone, by themselves.” Doing nothing with nobody, and doing it well, is a talent at living.

â

Paul Collins

Paul Collins

I

f things were as they should be, another kid would be telling you how to do these things, or you'd be telling another kid. But since I'm the only kid left around who knows how to do these thingsâI'm forty-two years old, but about these things I'm still a kidâI guess it's up to me.

f things were as they should be, another kid would be telling you how to do these things, or you'd be telling another kid. But since I'm the only kid left around who knows how to do these thingsâI'm forty-two years old, but about these things I'm still a kidâI guess it's up to me.

These are things you can do by yourself. There are no kits to build these things. There are no classes to learn these things, no teachers to teach them, you don't need any help from your mother or your father or anybody. The rule about this book is there's no hollering for help. If you follow the instructions, these things will work, if

you don't, they won't. Once you have built them my way, you may find a better way to build them, but first time, do them the way it says.

you don't, they won't. Once you have built them my way, you may find a better way to build them, but first time, do them the way it says.

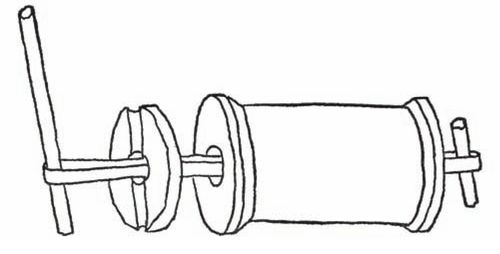

First thing is a spool tank. For this you need an empty spool. Here's one place your mother can be ootzed into the deal. You can ask her for a spool. If she hasn't got an empty one, you'll have to wait until she does. In the meantime, build something else.

HTDN_10

Okay, now you've got the spool. You will also need a candle or a piece of hard soap, a rubber band, and three or four large wooden kitchen matches. If you want to be real fancy and you've got a thumbtack, that's okay, but you don't really need it, and it's really not the right way to build a spool tank. The first thing to do is make the washer. Take

a kitchen knife or your jackknife. We used, sometimes, to hold the blade under the hot water until it got fairly warm, thinking it would make it easier to slice the candle, but I've just tried it, and I honestly don't think it makes any difference. You can try it both ways and see. Either way, what you do is cut a slice of candle, from the bottom of the candle. Cut it fairly thick, at least a quarter of an inch. The finished washer doesn't have to be that thick, but it's easier to cut a thick slice of the candle than a thin slice without its breaking. If the candle, when you cut it, looks as if it's made in thin layers, like an onion, forget it. You'll never get a decent washer out of it. Either find the kind of candle that's made solid, or use soap. If you find the right kind of candle, keep cutting slices until you get a good solid one. You may find it easier to pull the slice off the candle without cutting through the wick, leaving a hole. If you cut right through the wick, with one of your matches push out the little piece of wick in the center if it's still there. Now go outside and find a very smooth stone, like a sidewalk, and rub, gently, until the washer is nice and flat on both sides. You don't really need a stone, you can do it on a wooden floor, if your mother is somewhere else.

1

a kitchen knife or your jackknife. We used, sometimes, to hold the blade under the hot water until it got fairly warm, thinking it would make it easier to slice the candle, but I've just tried it, and I honestly don't think it makes any difference. You can try it both ways and see. Either way, what you do is cut a slice of candle, from the bottom of the candle. Cut it fairly thick, at least a quarter of an inch. The finished washer doesn't have to be that thick, but it's easier to cut a thick slice of the candle than a thin slice without its breaking. If the candle, when you cut it, looks as if it's made in thin layers, like an onion, forget it. You'll never get a decent washer out of it. Either find the kind of candle that's made solid, or use soap. If you find the right kind of candle, keep cutting slices until you get a good solid one. You may find it easier to pull the slice off the candle without cutting through the wick, leaving a hole. If you cut right through the wick, with one of your matches push out the little piece of wick in the center if it's still there. Now go outside and find a very smooth stone, like a sidewalk, and rub, gently, until the washer is nice and flat on both sides. You don't really need a stone, you can do it on a wooden floor, if your mother is somewhere else.

1

If you use soap, cut a slice with your knifeâyou don't have to heat the blade for soapâand then trim it round, and then poke a hole in the center, with the punch on your knife, or you can even do this with the matchstick too. With the matchstick, rub a little groove in the washer, or cut the groove carefully with your knife.

HTDN_12a

Then thread a rubber band through the hole, and put the matchstick through the loop it makes. Now work the rubber band through the spool. It's too short? Get a longer one. It's too long? Double it. Now break off a piece of another matchstick and put it through the rubber-band loop at the other end of the spool.

HTDN_12b

Wind it up, and then put it down. It will run across the floor, it will climb a considerable slope, and if it runs ahead of itself so the stick is in front instead of in back, just wait. The stick will come slowly up and over and when it touches the ground, you're in business again.

If you've wound it and it doesn't go because the washer won't turn, without taking the tank apart rub the washer against the spool just where it is. If the little matchstick at the other end skitters around, jam pieces of matchstick in the hole like this or use a thumbtack.

Other books

Hang In There Bozo by Lauren Child

Running Scared by Gloria Skurzynski

Happiness Key by Emilie Richards

A Tiger's Treasure (Tiger Protectors Book 2) by Terry Bolryder

Vicky Peterwald: Target by Mike Shepherd

The Suit and His Switch Claim Their Sub by Jenika Snow

A Southern Exposure by Alice Adams

The Gospel According to the Son by Norman Mailer

Neeri's Need: How to Crash a Party by Andromeda Bliss

Stranger to History by Aatish Taseer