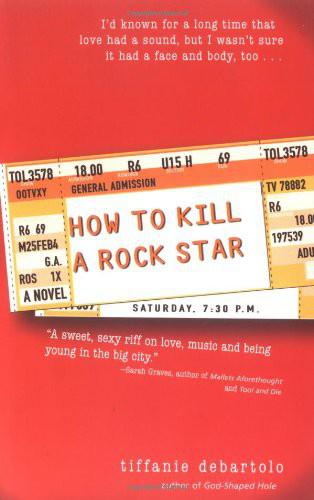

How to Kill a Rock Star

Read How to Kill a Rock Star Online

Authors: Tiffanie Debartolo

Tags: #Romance, #Contemporary, #Contemporary Women, #New York (N.Y.), #Fear of Flying, #Fiction, #Urban Life, #Rock Musicians, #Aircraft Accident Victims' Families, #Humorous Fiction, #Women Journalists, #General, #Roommates, #Love Stories

HOW TO KILL

A ROCK STAR

a novel

HOW TO KILL

A ROCK STAR

tiffanie debartolo

Copyright © 2005 by Tiffanie DeBartolo Cover and internal design © 2005 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

Al rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems–except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews–without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the fol owing material: “The Day I Became a Ghost” by Douglas J. Blackman

© 1977 Soul in the Wal Music

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

“Eliza” by Paul Hudson

© 2001 ScrawnyWhiteGuy Music

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

“Rusted” by Loring Blackman

© 2000 Two Fathoms Music

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

“A Thousand Ways” by Loring Blackman

© 2002 Two Fathoms Music

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

“Save the Savior” by Paul Hudson

© 2002 ScrawnyWhiteGuy Music

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

Excerpt from the novel

Hallelujah

by Jacob Grace.

Al rights reserved. Used by permission.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Napervil e, Il inois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

FAX: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeBartolo, Tiffanie.

How to kil a rock star / Tiffanie DeBartolo.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-4022-0521-X (alk. paper)

1. Women journalists--Fiction. 2. Aircraft accident victims' families--Fiction. 3. New York (N.Y.)--Fiction. 4. Fear of flying--Fiction. 5. Rock musicians--Fiction. 6. Roommates--

Fiction. I. Title.

PS3604.E233H69 2005

813'.6--dc22

2005012501

Printed and bound in the United States of America VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

We are the music-makers,

And we are the dreamers of dreams,

Wandering by lone sea-breakers,

And sitting by desolate streams;

World-losers and world-forsakers,

On whom the pale moon gleams:

Yet we are the movers and shakers

Of the world for ever, it seems.

—Arthur O

’

Shaughnessy

This one is for the music makers

and the dreamers of dreams.

I was only a child

when I learned how to fly

I wanted to touch the colors of the bleeding sun and then I fel from the sky

You never saw me again

not even when I returned

you never noticed my broken heart

or how my wings were burned

But if they tel you they saw me

do a swan dive off that bridge

Remember I’ve always been more afraid to die than I ever was to live

And on the day I disappear

You’l al forget I was ever here

I’l float around from coast to coast And sing about how you made me a ghost.

—Douglas J. Blackman, “The Day I Became a Ghost” How to Kil _internals.rev 2/22/08 4:59

PM Page ix part one

Save the Savior

My oldest memory isn’t one I

see

when I think back on the past, it’s one I

hear

. I’m four years old, on my way home from a camping trip with my family. My eyes are shut tightly and I’m trying to sleep in the backseat of the car. My six-year-old brother, who is already asleep, keeps kicking me in the head, and I am about to kick him back when the song on the radio gets my attention. The smooth voice of a man is singing about a pony that ran away in the snow and died.

Or maybe it was the girl chasing after the pony who died.

Maybe nobody died. The girl and the pony might have just wanted to get off the farm. I was never real y sure. Al I remember is that before I knew it, I was sobbing so hard my dad had to stop the car so my mom could pul me into her lap and calm me down.

The song was senseless and sappy, but it made me feel something. And although I couldn’t articulate it at that age, feeling something—anything— made me conscious that I was alive.

I would spend the rest of my childhood sitting beside radios, continual y being transformed and exalted by a melody, a lyric, or a riff.

I would spend most of my adolescence in pieces on the floor, only to be picked up and put back together by the voice of one of my heroes.

It sounds sil y, I know. But for me, the power of music

rests in its ability to reach inside and touch the places where the deepest cuts lie.

Like a benevolent god, a good song wil never let you down.

And sometimes, when you’re trying to find your way, one of those gods actual y shows up and gives you directions.

Doug Blackman even walked like a god. I was standing near the elevator when I saw him enter the hotel. His arms moved back and forth as if set to a metronome, his torso stood erect and intimidating, and his eyes seemed a step ahead of his body, unblinking, taking in everything his peripheral vision had to offer.

He stopped at the front desk to drop off an envelope, and seconds later he was standing beside me, fishing through his breast pocket. He smel ed like red wine and cigarettes, and his dark hair had wiry gray threads sewn al through it.

I told myself to stay cool. Don’t stare. Act like the adult I was. But I had imagined Doug coming in with an entourage, had thought I’d have to fight just to catch a glimpse. And then he was beside me, our shoulders inches from touching—the radio prophet who had taught me almost everything I knew about life and love, politics and poetry, and was, in my opinion, the greatest singer/songwriter in the history of rock ’n’ rol .

In person, Doug looked every bit his fifty-seven years.

His face was like a mountain range: he had deep fissures in his cheeks chiseled from over three decades of life on the road; dark, sharp eyes that could have been cut from granite; a smal chip in his top front tooth that he’d never bothered to fix; and his rumpled clothes looked like they’d been won from a vagabond during a street game of dice, which added a soft, modest charm to his otherwise unapproachable vibe.

I had a whole speech prepared, in case I got close enough

to talk. I was going to tel Doug that in my twenty-six years on the planet, nothing had inspired me or moved me like his music. I was going to tel him that for the past decade he had been both father and mother to me, and that “The Day I Became a Ghost” wasn’t just a song, it was a friend who took my hand and kept me company whenever I felt alone.

Nothing he hadn’t heard a thousand times, no doubt.

Before I could get a word out, Doug pul ed a deck of cards from his pocket and said, “Pick one.” I turned and said, “

Huh

?”

It would go down in history as the worst opening line anyone had ever said to their god and hero. I wanted to take it back and say something profound. The man had given me the truth and al I could give back to him was a dimwitted interjection.

“Pick a card,” Doug said again, holding the deck with both hands, the cards splayed out like a fan.

I was staring at him, wide-eyed, trying to wil myself to speak. It should be noted here that I make my living talking to people. I’m a reporter. Evidently gods and heroes tongue-tie me.

“Go on,” Doug said.

I chose a card out of the middle of the deck, quickly checked Doug’s eyes for some kind of explanation he clearly didn’t think he needed to offer, and then looked at the card—the three of clubs.

“This elevator takes forever,” Doug grumbled. “Four hundred bucks a night and it takes the elevator ten minutes to get to the lobby. Now, here’s what I want you to do. Write your name on the face of the card. It’s okay if I see it. You got a pen? Write your name on it and then put it back in the deck.”

I’m dreaming

, I thought. It was the only explanation I could come up with to balance out the surreal experience of participating in a card trick with Doug Blackman.

“Do–you–have–a–pen?” Doug said again, as if he were speaking to a foreigner.

The only pen in my purse had purple ink. Purple seemed frivolous and gay and not nearly rock ’n’ rol enough; I cursed myself for not buying black.

I put down my bag and began printing my name on the card. Doug was looking over my shoulder and I wondered if he could see my hand shaking.

“Eliza Caelum,” he said. “You from around here, Eliza?” I nodded.

“Put the card back in the deck.”

I did.

“You know who I am,” Doug said, not a question but a fact. He was shuffling the cards like a pro. “You were at the show?”

I nodded again. I was acting like an imbecile, and I knew I was never going to get anywhere if I didn’t snap out of it.

“Okay, now pick the top card.”

The top card was the ten of hearts, which devastated me.

I thought Doug had messed up and I didn’t want to have to tel him. Luckily he said, “Not yours, I know. Just hold it in your palm. Face down.”

I held the card, and Doug made like he was sprinkling some kind of invisible dust over it. “My grandsons love this shit,” he said. His hands were weathered and rugged and powdery-white. They looked like they’d feel cold to touch.

“Okay. Take a look.”

I flipped the card. It was the three of clubs with my name written in that gay purple ink. I could feel myself grinning, and for a second I forgot who the man beside me was. “Holy crap. How did you do that?”

Doug shrugged. “Magician, musician. Same thing. A little hocus-pocus and a whole lot of faith, right?” My insides were swirling. I was spel bound.

As the elevator opened, Doug looked at me and said,

“You wanna fuck? Is that what you’re waiting for?” He’d asked the question as if he were offering me a piece of gum or tel ing me to pick another card. And maybe it should have disappointed me a little. Okay, it did disappoint me a little. Doug is married, and barring the Greeks and Romans, gods and heroes aren’t supposed to be philander-ers. But I’m not that naïve. I’ve read

Hammer of the Gods

and

No One Here Gets Out Alive

. I know about life on the road.

I also know that people like to pretend it’s al about sex, when what it’s real y about is loneliness.

“Wel ?” Doug asked, stepping into the elevator.

I shook my head. I hadn’t gone there for sex. What I wanted and needed was guidance. Besides, Doug was a father figure to me, and I couldn’t have sex with any man who reminded me of my father.

I contemplated tel ing Doug I was a reporter, but I knew he didn’t talk to reporters. And I guess you could say that what came out of my mouth next was the figurative, not literal explanation of why I had been waiting for him.

“My soul is withering,” I said.

Doug’s eyebrows rose and he actual y chuckled. “Your

soul

is

withering

?”

Then I don’t know what came over me, but I burst into tears.

Doug kept his finger on the button to hold the elevator open, and I laid it al out for him in rambling, weepy discourse. I either had to flee the suburbs of Cleveland or suffer the death of my soul. Those were the choices as I saw them. My parents had died when I was fourteen; I’d feebly tried to slit my wrist at sixteen; my brother had moved to Manhattan with his wife a few years back; Adam, my boyfriend of six years, had run off to Portland with his drum set and Kel y from Starbucks; writing for the entertainment

section of the

Plain Dealer

wasn’t exactly a dream job for an aspiring music journalist; and, to top it al off, I only had four hundred dol ars in my bank account.

I was alone. In ways people aren’t supposed to be alone.

And sure, I could’ve stayed where I was, continued working my nowhere job, living in my nowhere apartment, eventual y marry some nowhere man, have a few kids and anesthetize myself with provincial monotony like most of my peers had done, and before I knew it I’d be six feet under.

I wanted more.

And I had hope.

“

I’m more afraid to die than I am to live

,” I told Doug, thinking that if I made my case using his prodigious lyrics, he’d be more apt to identify with my predicament.

The warning bel in the elevator was ringing but Doug didn’t seem to care. He contemplated me for a long moment and then said, “How the hel am I supposed to say no to those eyes, huh?”

I lowered my gaze and tried to smile.

“Al right,” he sighed. “Get in, Eliza Caelum.” I took a deep breath, stepped inside the elevator, and focused on the numbers above the doors while Doug pushed the button for the eleventh floor.