How to rite Killer Fiction (3 page)

Read How to rite Killer Fiction Online

Authors: Carolyn Wheat

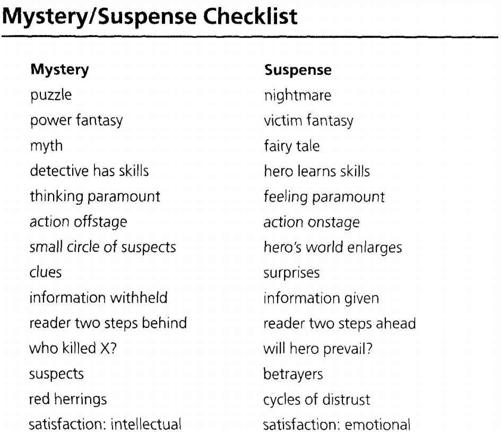

The rest of this book will explore the ways the writer makes the dream happen for the reader; it will follow the distinction between suspense and mystery, detailing the specific techniques that will best create each kind of dream. And it will discuss how to switch gears from mystery to suspense in order to add spice to the mystery, and how to plant mystery elements in the suspense novel that will add to its intellectual enjoyment.

Write What You Read_

Who's your favorite author, the one you turn to after a hard day at work, a day spent with three kids down with chicken pox, a day of dreary drizzle? Is it a classic whodunit in modern dress, a Carolyn G. Hart, a Margaret Maron, a Robert Barnard? Or is it a hard-boiled private eye—a Grafton, a Pronzini, a Paretsky, a Robert B. Parker? It could be that police or forensic procedurals like those of Patricia Cornwell, Ed McBain, or Kathy Reichs are your security-blanket reads.

Or is suspense your favorite escape? Perhaps Mary Higgins Clark, Barbara Michaels, or Dick Francis sweeps you away. Or maybe it's the techno or legal side of the thriller, with Clancy or Grisham, Crichton or Ludlum. Maybe it's the potent mix of suspense and mystery, as delivered by Jonathan Kellerman, T. Jefferson Parker, or Elizabeth George.

The major reason to identify your favorite kind of book is so you can read like a writer. As you read your favorite author, ask yourself what it is about the book that brings you into the story, what keeps you turning the page. Identify the particular pleasures of the book, and try to figure out exactly how the writer created those pleasures on the page. When you come to write your own novel, you'll find that the techniques your favorite writer used are accessible to you as well.

WE ENTER the funhouse of mystery, and the first question many ask themselves is: What the heck is a funhouse?

Ah, youth. Sometimes called the Crazy House, the funhouse was a mainstay of old-fashioned carnivals and midways, the kind of amusement parks people went to before Walt Disney discovered Anaheim. Check out some old newsreel footage of Coney Island if you want the full picture, and this is what you'll see:

Welcome to the Funhouse_

It's dark inside. You enter through a giant clown's head with an open mouth that becomes a door. Once inside, things happen without warning. You turn a corner and a skeleton pops out of the wall, stopping inches from your face. Maniacal laughter comes out of nowhere, and blasts of cold air meet you when you enter another corridor.

Nothing is what it seems. You're in a maze, where a wrong turn leads you to a blind alley, a dead end. You encounter floors that move unexpectedly, shift and tilt and have you sliding backwards, grabbing at the walls. Skulls on springs jump at you and taunting Joker-like voices dare you to take the next pathway.

You walk into the hall of mirrors and become part of the entertainment. Distorting mirrors make you look like a plump dwarf one minute, a skinny giant the next. Rows of mirrors one after another create an

infinity effect that makes it seem as if you'll never get out of the funhouse, that you might be trapped in a place of dangerous illusion forever. When you want to leave, you're led down corridors that go nowhere, diverted back to where you've already been, guided through a maze that ends (at least this is how it ended at my childhood amusement park, Sandusky's Cedar Point) with a huge polished wooden slide. Attendants give you a tiny rug to sit on and then push you down, down, down the slick surface to the ground floor and out into the sunlight where you blink as if you've been inside for a week.

What does this have to do with murder mysteries?

It's been forty years or more since I experienced the Cedar Point funhouse (for some reason, they just don't exist anymore, not the way they used to), and it still remains in my mind the most powerful metaphor I can think of for the well-plotted detective story. Things come out of the blue; the detective walks down dead-end pathways and finds the truth obscured by distractions and distortions. Even the detective herself seems distorted, changed, by the act of investigating the crime.

Just when the detective thinks she has it all figured out, someone puts her on a slick slide to nowheresville, and she's back on the street with nothing.

A Little Mystery History_

The idea of the detective all but preceded the reality. Mystery's founding father, Edgar Allan Poe, set his 1841 short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" in Paris because Paris, unlike most major cities of the day, actually had a police force with a detective division. Poe called his story "a tale of ratiocination" and introduced the amateur detective who reasoned rings around the official police investigator, bringing logic and science to bear on the problem of crime.

In Poe's stories and in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes adventures, the amateur detectives use scientific methods, while the police prefer using street informers and beating confessions out of the usual suspects. The detectives, C. Auguste Dupin and Sherlock Holmes, are the ones on their knees picking up threads and hairs, and they see beyond the obvious in ways the stolid, less-educated police detectives can't.

Poe bequeathed the mystery writer two very important principles: "the impossible made possible"—the Locked Room Mystery (as exemplified by "The Murders in the Rue Morgue"), and "the obvious made obscure" ("The Purloined Letter.")

These principles embody the funhouse experience: What you see is most emphatically not what you get. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," we're introduced to the first of many fictional murders that seem inexplicable. The room is locked; the windows are high and too small for a person to have entered. Yet there are dead bodies inside; the thing happened even though it couldn't possibly have happened.

The police are baffled—and baffled police are always good for the amateur detective—because they can't, in that most nineties of cliches, think outside the box. A person couldn't have scaled the walls and entered the room—but what if the murderer

isn't

a person? (No, we're not talking supernatural agencies here; if you don't know who committed the murders in the Rue Morgue, find a collection of Poe stories, because some things you have to experience for yourself.)

Locked Room Mysteries aren't the only venue for the "impossible made possible" strain of mystery plot construction. Any murderer who fakes an alibi is creating an "impossible" situation—nobody can be in two places at once—and making it "possible." In the same vein, a killer who creates the illusion that his victim is alive after the murder has been committed also makes the impossible possible.

The second principle, "the obvious made obscure," is another linchpin of the detective story. In "The Purloined Letter," Dupin is called in when the French police fail to find an important letter they know is hidden in an apartment. They've lifted floorboards and axed into walls, they've taken apart the stove and looked inside every book in the library, but they haven't looked in the one place that seems too obvious, too stupid, too mindless to constitute a successful hiding place.

"Hide in plain sight" will be one of the main methods of clue concealment we'll discuss later in this book. It's your job as the mystery writer to create clues leading to the identity of the murderer and then to conceal those clues in a way that fools the reader without making a fool of him.

That Was Then, This Is Now_

"Okay, so Edgar Allan Poe invented the detective story and got an award named after him. What docs that have to do with my writing a mystery novel in the twenty-first century?"

Plenty, if only because that original template for the tale of detection is imprinted on the brains of everyone who ever reached for a library book because it had a little red skull stamped on the spine. The mystery reader opens a book with certain expectations, and the writer who knows what those expectations are can give the reader what she wants in a way that delights and surprises her.

What's happened to the mystery since Holmes hung up his deerstalker and started keeping bees? For one thing, it split into three distinct strands, all of which are still very much in evidence on the bookstore shelves.

The Classic Whodunit

Poet and mystery reader W.H. Auden called it "the dialectic of innocence and guilt." Today's fans call it the "cozy," meaning no disrespect but expressing perfectly that feeling readers of the traditional mystery get

when

they pick up a new whodunit, go home and make tea, and wrap themselves in a physical quilt as well as the metaphoric quilt of a story they know will have a happy ending.

The happy ending—okay, "happy" may be going too far—the

positive

ending, the ending that brings justice to bear on a violent situation, the ending where reason triumphs over evil; that's the ending classic readers are looking for.

Why? Because ever since Poe, the classic tale of

detection

has

meant

restoring order to a world that was once well ordered but lost that serenity through violent death.

Auden calls the scene of the crime before the murder is committed "the great good place." It is the English village, the manor house, the theater, the university, the monastery, any place that thrives upon stability and hierarchy. Into this idyllic world step not one, but

two

undesirables: the killer and her victim. The killer rids the great good place of the victim; it's up to the detective to flush out and remove the murderer and restore goodness.

Subgenres of the traditional mystery include:

The Regional Mystery

The old-time traditional whodunit placed little emphasis on setting except insofar as it furthered the puzzle itself. The grand country house could be in any part of England, the sinister university or the bedeviled

theater could be anywhere in Britain, the U.S., or New Zealand—we weren't reading for a travelogue or for insight into local culture.

Tony Hillerman helped to change all that. His mysteries took place on Navajo lands, and the land itself was a major factor in creating the circumstances and the means for murder. The people and their culture were important to the solution of the mystery, which could not have been solved by an outsider without knowledge of Navajo myth and mindset. Even though Hillerman's detectives were police officers, the experience of reading about an exotic place and seeing it through the eyes of someone with deep understanding of the place and its people whetted mystery readers' appetites for more of the same, only different.