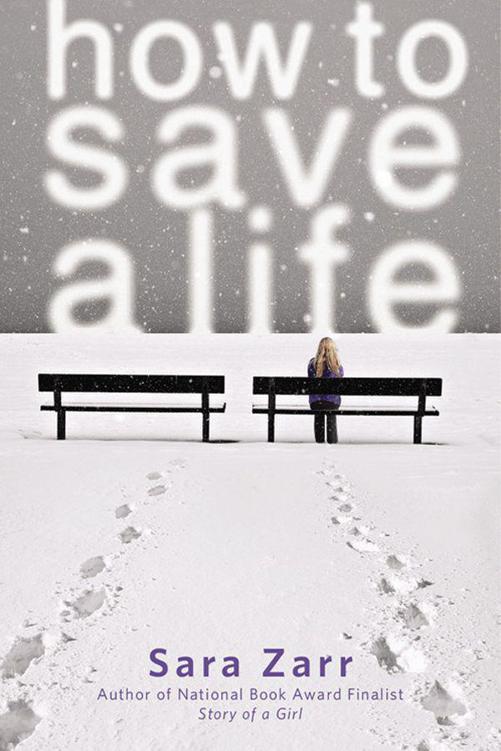

How to Save a Life

Read How to Save a Life Online

Authors: Sara Zarr

Little, Brown and Company

New York Boston

Jen, this one is for you, with love.

“

The life you save may be your own

.”

—Flannery O’Connor

From:

MMK333

To:

heart_homeDen

Subject:

Re: [lovegrows] Christmas wish

Date:

Jan 1 03:09:47 AM UTC-6

I am writing in response to your Love Grows post from Christmas Day.

I think I might have what you’re looking for.

It should be available on March 1. Or around March 1.

Right now I am living in Omaha, but this is not where I want to be. So if you pay my way, I will bring it to you in Denver. If that is where you really live. No offense but a lot of people on this site lie. I know they all say don’t send money and don’t send tickets and don’t do this and don’t do that. Rules don’t always apply, though, and you never know what another person has gone through to end up here. After reading your post, I knew you would understand this.

No lawyers. No agencies. That’s why I am on this site. If either gets involved, I will disappear with the item in question. I don’t mean to sound threatening. That’s just the situation.

I would like to come a little bit early and have the matter taken care of there. This way we can get to know each other. I’m not asking for money. Just expenses. It’s getting hard for me to stay here much longer.

This offer is good until one week from today. After that I will seek other solutions. I’m sorry if I’m rushing you, but you have to understand—I’m trying to do what’s best. I have attached a picture of myself and as you can see I am white and in good health and not bad-looking.

A lot of people in my situation might have a problem with some of the facts you mentioned in your post about you. Not me, because I think I understand.

If you accept me, I accept you.

Please write soon.

Mandy

Dad would want me to be here.

There’s no other explanation for my presence. Sometimes it’s like I exist—keep going to school, keep coming home, keep showing up in my life—only to prove that his confidence in me, his affection for me, weren’t mistakes. That I’m the person he always said I was. Am. That I know the right things to do and will always do them in the end, even if it takes me a while to get there and even if I fight the whole way.

We were the same that way. Are. Were. He was, I am. When he was here, I knew who I was. If I forgot, he’d remind me. In theory, I should be the same person now I was then. He died, not me. So I’m trying to be that person, still, even though he hasn’t been here for ten months now.

But let me tell you: It’s epically, stupidly, monumentally

hard

.

Hard to deal with people who are only trying to be nice, comforting. Hard to not hate all my friends who still have their dads. Hard to smile and say “thank you” to all the random strangers I deal with in a day who don’t know any better than to act as if the world is a good place.

The hardest thing of all is loving my mom without him to show me how. Loving, maybe, isn’t the best way to put it. Obviously, I love my mom. Understanding, appreciating, showing kindness and compassion and basic friendliness toward—which, you know, are the things that express love, because otherwise it’s just a word, right?—those are the challenges.

Especially understanding. Especially when she’s making lunatic decisions, like the one that’s led us here to the train station at seven o’clock on a Monday morning. Instead of celebrating Presidents’ Day the way it’s meant to be celebrated—with sleep—we’re waiting for the human time bomb that’s about to wreck our lives. Wreck it more, I mean. That’s my opinion, and it’s no big secret. Mom knows how I feel about this; she just doesn’t seem to care.

It’s a grief thing. Anyone from the outside looking in can analyze what’s going on and see it, except she claims this isn’t about that, not directly. Eventually I had to stop arguing with her; my rants only make her more stubborn about seeing this through. Not that I’m unfamiliar with stubbornness, and not that I’ve done such a fantastic job handling my own grief. But at least I’ve tried to limit the stupid shit I’ve done so that I’m the only one who gets hurt.

This? This affects three lives. Soon to be four.

“Sun,” Mom says now, stretching to see out the high, narrow panes of the station windows. There’s a glimpse of winter sky growing blue. When we got here, we found out that because of security rules, we couldn’t actually wait out on the platform, which somewhat shattered Mom’s romantic vision of how this whole thing would go down. Threat level Orange tends to do that.

I know I shouldn’t say this—I know it as surely as I know the earth is round and beets are evil—and yet here it comes: “It’s not too late to change your mind.”

Mom, still staring up at the windows, lets her bag slide off her shoulder and dangle from her elbow. “Thanks, Jill. That’s tremendously helpful.”

If I had any sense, the edge in her voice would shut me up. Alas. “You’re not obligated, like, legally. You didn’t sign any papers.”

“I’m aware.”

“You could put her up for a night in a hotel, then pay her way back home tomorrow. You could say, sorry, you made a mistake and didn’t realize it until you actually saw her and it hit you.”

Mom hoists her bag back up and walks closer to the doors under the

TO TRAINS

sign. Once there, she strokes her left jawline, where I know there’s a small mole, almost the same color as the rest of her skin, so you don’t really notice it, but it’s raised enough to feel. When she’s nervous, agitated, pissed off, or deep in thought, she runs her fingers over it nonstop.

I sink my hands into the pockets of my peacoat, trying to warm them up and also feeling for my phone.

Don’t check it

, I think.

Don’t check for a message from Dylan because there won’t be one

.

Mom looks so lonely over there. No Dad beside her to rest his hand on her shoulder, the way he would. I could do that. How hard can it be? I move closer. Tentatively lift my arm. She turns to me and says, “You’re the sister, Jill.”

My arm drops.

The sister. It’s so hard to get there mentally. Yes, when I was a kid, I desperately wanted a baby brother or sister, but at seventeen it’s a different scenario.

Mom looks at her cell and fluffs her cropped hair. It’s a new look for her, one I’m not used to yet. “Why don’t you go ask if there’s a delay.”

I leave her there to her mole and her thoughts.

The station, with its soaring ceilings and old marble floor, is echoey with pieces of conversations and suitcases being rolled and the

thwonking

of a child’s feet running up and down the seat of one of the high-backed wooden benches. “No, no, Jaden, we don’t run indoors,” the mother says.

Thwonk thwonk thwonk

. “What did I just say, Jaden? Do you want to have a time-out?” Pause.

Thwonk thwonk thwonk thwonk

. I can see the top of Jaden’s head bobbing along as his mother counts down to time-out. “One… two…”

Thwonk

. “Three.”

Thwonk thwonk

. “Okay, but remember you made the choice.”

Jaden screams.

This is what we have to look forward to.

Why my mother would want to put herself through all this again is a mystery to me, no matter how she’s tried to explain it. When she announced over tuna casserole six weeks ago that she was going to participate in an open adoption, I laughed.

She frowned, fiddled with her napkin. “It’s not funny, Jill.”

“This is just an idea, right? Something I could potentially talk you out of?”

“No.” Her hand went to her left jaw.

If I didn’t know my mom so well, I wouldn’t have believed her. But this was completely consistent,

so

something she would do. She’s never been one to solicit opinions before making major decisions. It drove Dad crazy. She’d go trade in her perfectly fine car for a brand-new one, or book a nonrefundable vacation on a total whim. Then there was the time she decided she wanted to paint every room in the house a different color and started one Saturday while Dad and I were at the self-defense class he made me take. We came home and the living room had gone from white to Alpine Lake Azure. Surprise! I didn’t really care, but Dad was so aggravated.

This, though, I cared about, and when I realized she was serious, I said, “It’s insane.”

“War is insane. The fact that there’s still no cure for AIDS is insane. This is not insane.”

“You’re old, Mom!”

“Thanks, honey. Early fifties is

not

old.”

“When the kid is my age, you’ll be—”

“Seventy. I can do math, Jill.”

“Seventy is

old

.”

Everything was in its normal place: the old wooden farm table in front of me, the iron pot rack over the stove, the cigar box full of stamps at the end of the counter near the phone. Our quiet street outside. Yet this conversation? Not normal. She remained so perfectly calm through it all that I had to say several times, “You do realize you’re talking about

adopting a baby

?” to make sure we were living in the same reality.