How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare (35 page)

Read How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Online

Authors: Ken Ludwig

Tags: #Education, #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Arts & Humanities, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #General

Speech 2: The Saint Crispin’s Day Speech

Another famous speech from

Henry V

is known as the Saint Crispin’s Day Speech, and it occurs just before the Battle of Agincourt. Henry’s nobles are having a discussion among themselves, worrying that the French outnumber them five to one. One of the nobles, the Earl of Westmoreland, wishes aloud that some of the idle men at home in England were with them now in France to help them fight:

O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work today

.

Henry’s famous speech is in reply to Westmoreland. Again, here is a slightly cut version that is perfect for recitation contests.

| Shakespeare’s Lines | My Paraphrases |

| If we are marked to die, we are enough | If we are destined to die, there are enough of us to be a loss to our country; but if we’re going to live, then the fewer we are, the more glory we’ll earn. So please don’t wish for any more of us. |

| To do our country loss; and if to live , | |

| The fewer men, the greater share of honor . | |

| God’s will, I pray thee wish not one man more . | |

| By Jove, I am not covetous for gold , | By heaven, I don’t covet gold, I don’t care who eats at my expense, and I don’t care if men wear my clothing. Such outward things don’t bother me. But if it’s a sin to covet honor, then I’m the most covetous person alive. No, don’t wish for any more men from England.… |

| Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost; | |

| It yearns me not if men my garments wear; | |

| Such outward things dwell not in my desires . | |

| But if it be a sin to covet honor , | |

| I am the most offending soul alive . | |

| No, ’faith, my coz, wish not a man from England .… | |

| Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host , | Rather, make an announcement to my troops that if anyone doesn’t have the stomach for the fight ahead, let him leave. We’ll give him a passport and some money. We don’t want to die in the company of any man who doesn’t want to die with us. |

| That he which hath no stomach to this fight , | |

| Let him depart. His passport shall be made , | |

| And crowns for convoy put into his purse . | |

| We would not die in that man’s company | |

| That fears his fellowship to die with us . | |

| This day is called the Feast of Crispian . | Today is the Feast of Saint Crispin. Anyone who lives through this day and gets home safely will stand on his tiptoes and raise a cheer whenever, in the future, he hears the word Crispin.… |

| He that outlives this day and comes safe home | |

| Will stand o’tiptoe when this day is named | |

| And rouse him at the name of Crispian.… | |

| Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot , | Old men forget things; indeed, everything will be forgotten, but the men who have fought with us today will remember “with advantages” what they did today.… |

| But he’ll remember with advantages | |

| What feats he did that day.… | |

| This story shall the good man teach his son , | Good men will tell the story of this day to their sons, and the anniversary of this day will never go by without our being remembered for our valor— |

| And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by , | |

| From this day to the ending of the world , | |

| But we in it shall be rememberèd— | |

| We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; | We happy few, we band of brothers. I call you brothers because whoever sheds his blood with me today, no matter how lowly his origins, will be my brother, because by fighting today he becomes more noble. |

| For he today that sheds his blood with me | |

| Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile , | |

| This day shall gentle his condition; | |

| And gentlemen in England now abed | And noblemen who are in bed right now back in England will feel deprived and will think less of themselves because they never got to fight by our side on Saint Crispin’sDay. |

| Shall think themselves accursed they were not here , | |

| And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks | |

| That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day . |

What a speech! What a rallying cry of sheer patriotism!

One of my favorite sections of the speech is this:

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot

,

But he’ll remember, with advantages

,

What feats he did that day

.

Shakespeare starts the line with a fond observation about mankind as it grows older:

Old men forget;

Then he adds the observation that in the sands of time, all that we do will be forgotten:

yet all shall be forgot

Then he adds a joke, a warm, human, touching joke:

But he’ll remember

,

with advantages

,

What feats he did that day

.

The old man won’t just brag about his exploits in the war; he’ll exaggerate the exploits

with advantages

. Only Shakespeare could pack this much wisdom, humor, and humanity into three short lines.

You should also point out to your children that the whole notion of centering the speech on Saint Crispin’s Day is a bit of happenstance. The text of the speech can be confusing otherwise. Why Saint Crispin? Was he a famous fighter or hero? Not at all. The Battle of Agincourt happened to fall on a saint’s day in the calendar (October 25) honoring Saint Crispin, the patron saint of cobblers and leather workers. Shakespeare seized on this fact as a way of identifying the day for rhetorical purposes.

Many a middle-schooler has won a recitation contest with this speech and for all the right reasons. It is long enough to show effort; it is complex enough to show intellectual accomplishment; and if recited well, there is no more stirring speech in the English language.

Hooray for Heminges and Condell

I

n addition to William Shakespeare, there are two other heroes in this book, and their names are John Heminges and Henry Condell. It’s a scandal that there aren’t statues of these two men in front of every library in the world, and I hope that you and your children will help me rectify this situation.

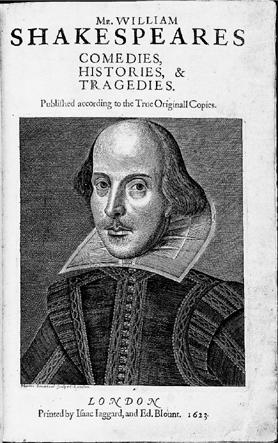

Heminges and Condell were close friends, fellow theater owners, and acting colleagues of Shakespeare, but their greatest achievement was that they published the first edition of Shakespeare’s complete plays in 1623, seven years after his death. The book was formally titled

Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies

, and it is known as the First Folio. The remarkable thing is that without the First Folio, we would not have

eighteen

of Shakespeare’s plays. Since none of Shakespeare’s manuscripts survive, and none of these plays appeared first in surviving “quarto” editions, these eighteen plays would have been lost forever had it not been for these two men. We wouldn’t have

Twelfth Night, As You Like It, The Tempest, Julius Caesar, The Taming of the Shrew, Antony and Cleopatra

, and twelve others.

And it is not just these eighteen plays that were saved. Some of Shakespeare’s plays that

were

published in his lifetime were printed in such corrupt versions that they are almost unrecognizable as Shakespeare plays. The First Folio was published to set the record straight and make certain

that authorized, quality texts of all of Shakespeare’s plays were available to the public. Thanks to Heminges and Condell, the course of literary history was changed forever.

To appreciate the full accomplishment of Heminges and Condell, your children should understand a little about the publishing history of Shakespeare’s plays. When Shakespeare wrote a play, it was purchased outright by the acting company for which it was written. Thus most of Shakespeare’s plays were eventually owned by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, which then became the King’s Men. Shakespeare himself no longer owned his plays; and moreover, he had no right to protect the integrity of his words because at this time there were no copyright laws as we know them today.

When Shakespeare’s plays were performed, some of them were so popular that Shakespeare’s company decided to make additional money by

selling them to publishers, who printed them in editions called quartos. A quarto is the equivalent of a modern paperback. It is called a quarto because the pages are made by folding a large sheet of paper twice (into a quarter of its original size), then binding the book on one side and cutting the pages open. A folio is twice as big because the sheets were folded only once. A folio was often bound with a leather cover and was equivalent to a modern coffee-table book.

The title page of the First Folio

(photo credit 31.1)

Scholars have divided the quartos into two kinds. The “bad quartos” were apparently patched together from various sources, such as partial scripts, actors’ memories, or the scribblings of plagiarists who were planted in the audience; the “good quartos” were usually printed directly from the author’s or a scribe’s manuscripts, or from the manuscripts used as promptbooks. Prior to the printing of the First Folio, some of Shakespeare’s plays were available only as bad quartos, and some of them are pretty bad indeed. Take, for example, Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, which appears like this in the good quarto:

To be, or not to be—that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And, by opposing, end them. To die, to sleep—

No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished

.

The bad quarto of

Hamlet

reads like this:

To be, or not to be, I there’s the point

,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all:

No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes

,

For in that dreame of death, when wee awake

,

And borne before an everlasting Judge

,