How to Walk a Puma (19 page)

Read How to Walk a Puma Online

Authors: Peter Allison

The trip out would involve a two-day stint in the canoe, but first Otobo needed to take his youngest daughter back to Bameno, four hours downstream and five back. Always keen to see what wildlife might be beside the river, I piled in too. Big mistake. Unlike the shaded smaller tributaries that criss-crossed around us, the Cononaco was broad, and open. A few days earlier, my camera battery had died, and my sunscreen ran out soon after. The first loss was merely sad, but the second was dangerous considering my new penchant for bare-arsed exploration; very soon not an inch of me was spared from being burnt, much to the Huoarani’s amusement. Learning as I was, I had just pointed at my pink bits and laughed back. But while earlier I had been merely pinked, by the end of the day I was traffic-stopping red, and exuding so much heat that Otobo’s wife hung wet clothes near me, saying I would dry them faster than the fire. It would have been merely uncomfortable and led to no more than a restless night in my hammock, but I would have to spend two more days in the canoe before hitting Coca and the chance of some soothing lotion, no doubt needed after another two days of

skin-ravaging

travel to get out.

I waved goodbye to Omagewe and his wife, who would not accompany us, and I wanted to say that my time with them had been fantastic, and to thank them profusely, but was still limited to a mere

‘

Waponi

,’ which for the first time felt woefully inadequate. Omagewe waved from the bank, laughed, shouted ‘

Waponi!

’ back at me and walked away before we were out of sight, off to live the life he has lived since before outsiders even knew of his existence.

It rained, hard and ceaselessly, for our first day’s travel. Even the stoic Otobo took a T-shirt I offered him; although it immediately became soaked it offered some insulation.

My three weeks with the Huaorani had left me bearded, bedraggled and bemoulded, but as we camped in the jungle that night I knew I would miss it painfully. A smoky jungle frog called nearby, one of my favourite sounds. I kept an ear peeled, listening for another sound, one Marcello had taught me—a long rasp of a call that would tell me that there was a jaguar close by—but all that night I lay sleepless, and no such sound came. I wanted the miracle—golden eyes peering from the forest as we broke camp or piled into the canoe, or a flash of fur as we motored along—but this was no fairytale, no fantasy, and a jaguar did not appear.

The next day, we motored upriver for what seemed an

anticlimactically

short time and arrived back at the checkpoint, and soon after that I was on a bus back to Coca, travelling alongside jungle that had been scorched and slashed.

If I had learnt anything from the Huaorani it was that the trick of life is not to be content with what you have, but to be happy with what you do not. The trip was never really about jaguars anyway, or birds, or about finding myself, losing myself, or defying my age, but about seeking something wild and rare, not just in the jungle, but in me. I’d feared that too many years of desk-bound normalcy had killed off this part of me, but chasing the jaguar took me to so many places that I would never have been if I’d owned a fridge. I came to South

America to find a jaguar, but came away with so much more. I found a truly wonderful girlfriend, a country that made adversity into something uplifting, the scariest pet you could ever have; at the same time, I learnt that constant travel is exhausting, and that maybe, just maybe, it is okay to settle down. For a little while, anyway.

Of course, I didn’t find the jaguar, but that just means I have to keep looking.

I often wish life was like a story that you could go back and edit if it didn’t work out, but I can’t think of much that I would change about my eighteen months in South America. Overwhelmingly my memories are happy ones, but some are tinged with sadness.

Hollywood would have us believe that accidents happen in slow motion, and that the greatest challenge to romance is some obstacle and, with that overcome, all will be triumphant. But of course accidents come at full and out-of-control speed like a crazed puma or a raft being sucked into a whirlpool, and the hardest romantic endeavour is not to get together, but stay together. After leaving South America I flew to London to be reunited with Lisa, but I couldn’t stay in London long, and the strain of too much time and distance meant that the Minke and I decided to end our relationship. We remain friends, and I will forever be glad for her company through so much of the trip.

At the time of writing I am employed in a job I love, working with colleagues I consider friends and on occasion even respect, travelling the world and quite enjoying the looks people give me when they see the dirty, frayed piece of string around my waist.

My sincere thanks go to the following people:

Harris and Marguerite Gomez for giving me the softest landing imaginable in South America, and being such wonderful friends.

Pete Oxford and Renee Bish, wildlife photographers

extraordinaire

, for saving my bacon, then putting it in some of the most exciting situations I have experienced. Much of this book would not have come about without their advice and introductions.

The Minke, for more than can be said or written.

Tom Quesenberry (now that’s a funny name, isn’t it?) and Mariela Tenorio, who run the beautiful El Monte Lodge in Mindo, for arranging and assisting with so much of the Huaorani trip, and laughing as heartily as the Huaorani at all my maladies.

Bec Smart, Bondy, Mick Payne, Adrian, Rob Thoren and Nina at Inti Wara Yassi.

Sam Sudar for getting in a car with me.

Julio, the night watchman at Hostel Americana in El Calafate.

Marcello Yndio, for the way he killed a chicken.

Peter Fitzsimmons, for coffee, advice, and constant reminders that he sells more books than me.

Guillerme and Andres at the Sacha office, Tomas the manager, as well as all the staff at Sacha Lodge for making my stay there so pleasurable and monkey-filled.

Aaron Sorkin for answering so many questions, and the Undeletables for laughs and thought-provoking debate.

Marcella Liljesthrom for the swallows.

Friederike ‘Wildchild’ Wildberg for some wise words, but mainly for being German yet funny.

Lloyd Temple Camp, because he wants to be mentioned in a book.

Donald Brown for the same reason (and yes, yes, yes, it is true, he also kept me employed for several years when few people would).

Tarli Young for saving me from a planned life of luxury and comfort in Costa Rica, and inadvertently sending me to Bolivia and Inti Wara Yassi instead.

Ben and Kate Loxton for insisting I waste some time in debauchery and laugh myself silly while doing so. And Yahtzee too.

Diana Balcazar for expert guiding while filming in Colombia.

Matt Mitchell and Jonny Hall at Hostel Revolution, Quito.

John Purcell and Tamsin Steel for putting me up—and putting up with me—when I was recently single and a moping dullard.

Louis, Hoens and Jan Louis Nortje who gave me somewhere to stay during the main editing phase of this book, far from South America in Namibia.

And finally, thanks to the team at Allen & Unwin—Louise Thurtell, Clara Finlay and Angela Handley.

Peter Allison has led safaris in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. It was his love of animals that first led him to Africa at the age of 19, and by the late 1990s he’d graduated from being a safari guide himself to leading the training of guides for the region’s largest safari operator. Peter has led safaris that have featured in such magazines as

Vogue

and

Conde Nast Traveller

. He has also assisted

National Geographic

photographers and appeared on television shows such as

Jack Hanna’s Animal Adventures

. In between globetrotting the world as a marketeer for Africa’s leading safari company, he divides his time between Sydney and Cape Town.

Roy the puma loved his jungle trails, but also had a strange penchant for walking on top of pipes. The Roy Boys would try to emulate him—the first person to slip had to buy that evening’s beers. And would most likely get bitten for their impudence.

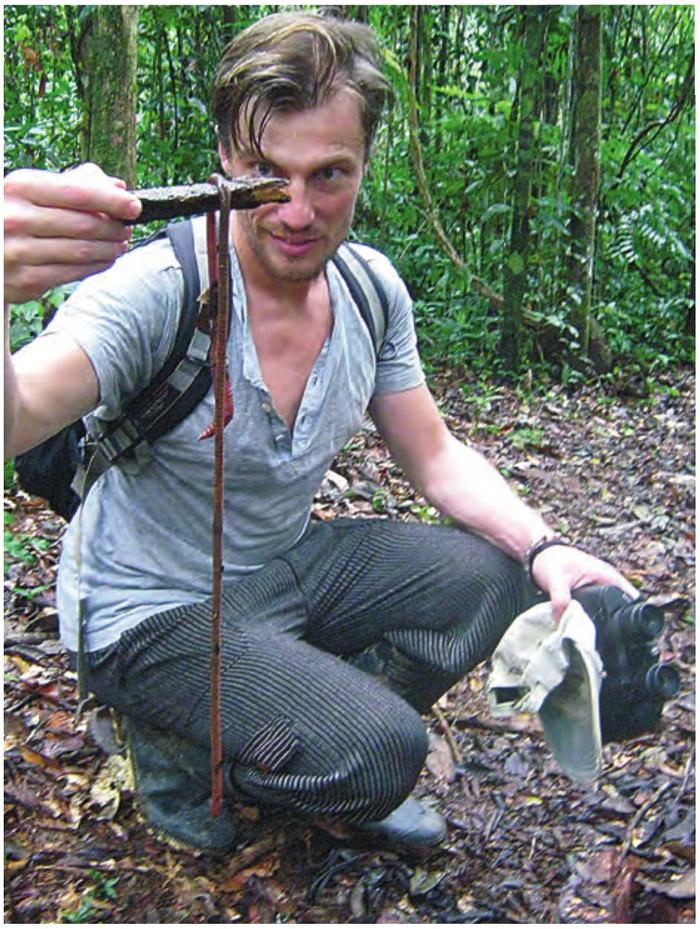

Pumas and jaguars may seem fierce, but South America’s deadliest animals are frogs with skin so poisonous just touching them can be fatal. I probably shouldn’t have picked this little fellow up then.

This squirrel monkey made himself an inverted hammock outside my room at Sacha Lodge.

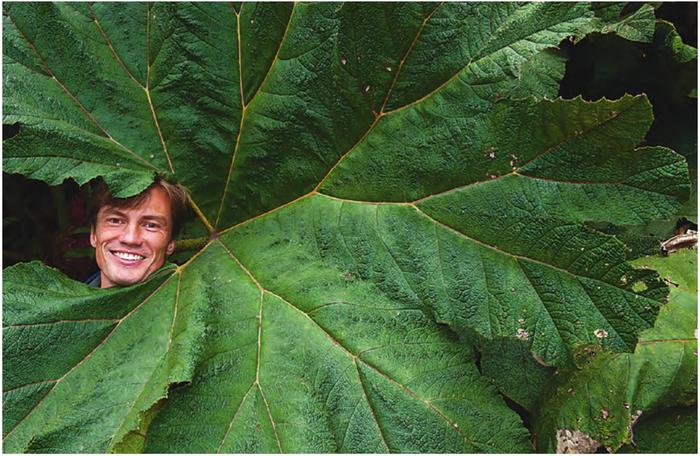

Cabbage Patch Kids grow up eventually. Maybe one day I will too.

Detail of a Bird of Paradise flower, an example of the extravagant flora in the Amazon basin.

… almost as extravagant as the insect life (right)—this fellow is a Lantern or Peanut Bug. The Kichwa believe that if one bites you you must have sex within 24 hours or die. I’m pretty sure a man came up with that.

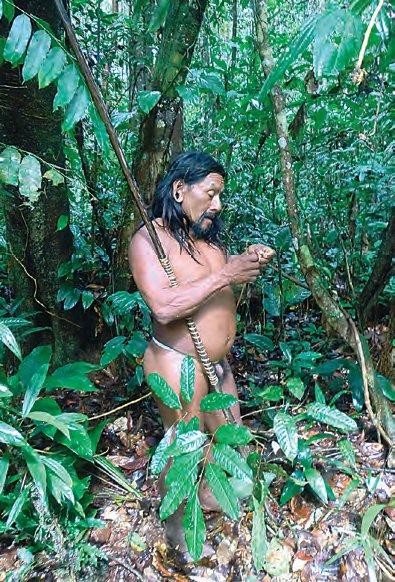

The amazing Omagewe, born before his tribe (the Huaorani) had any contact with the outside world and still living a mostly traditional lifestyle. He showed me the jungle in a way few living people could.

The caecilian looks like an overgrown earthworm the size of a snake, but is neither. It is one of the bizarre animals that attracted me to South America—an amphibian that lives underground.

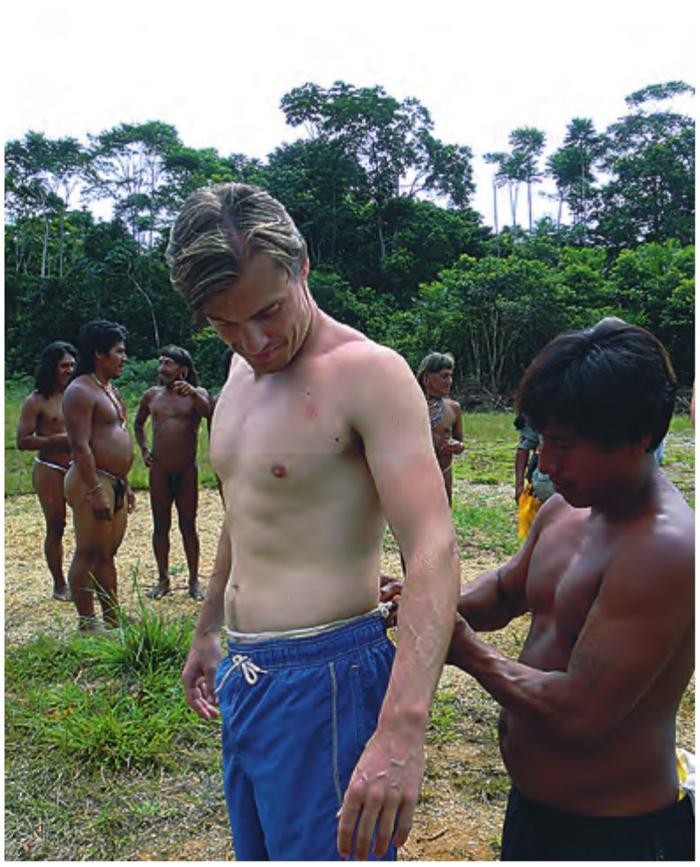

Getting fitted for my string (made from the fibres of a local palm tree)—the string would be all I wore for much of my time with the Huaorani.

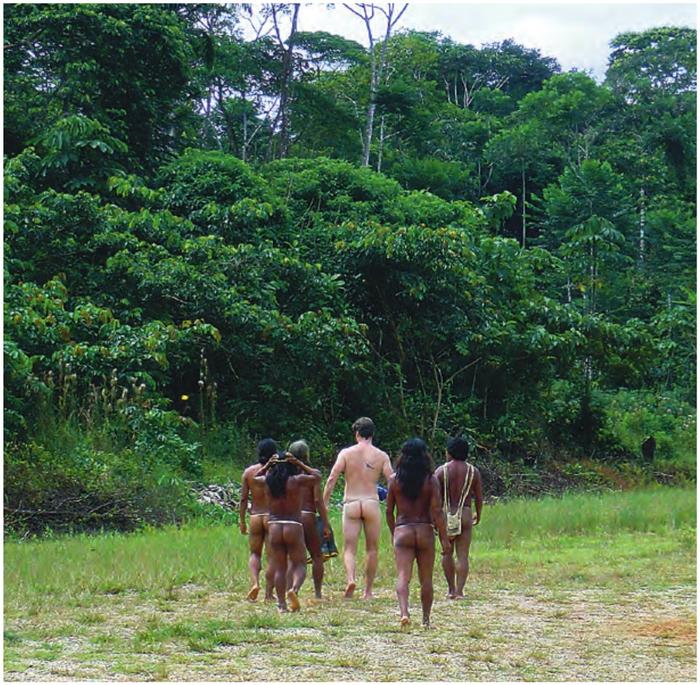

… all I wore apart from sunscreen, which I was sorely in need of, and merely sore without.

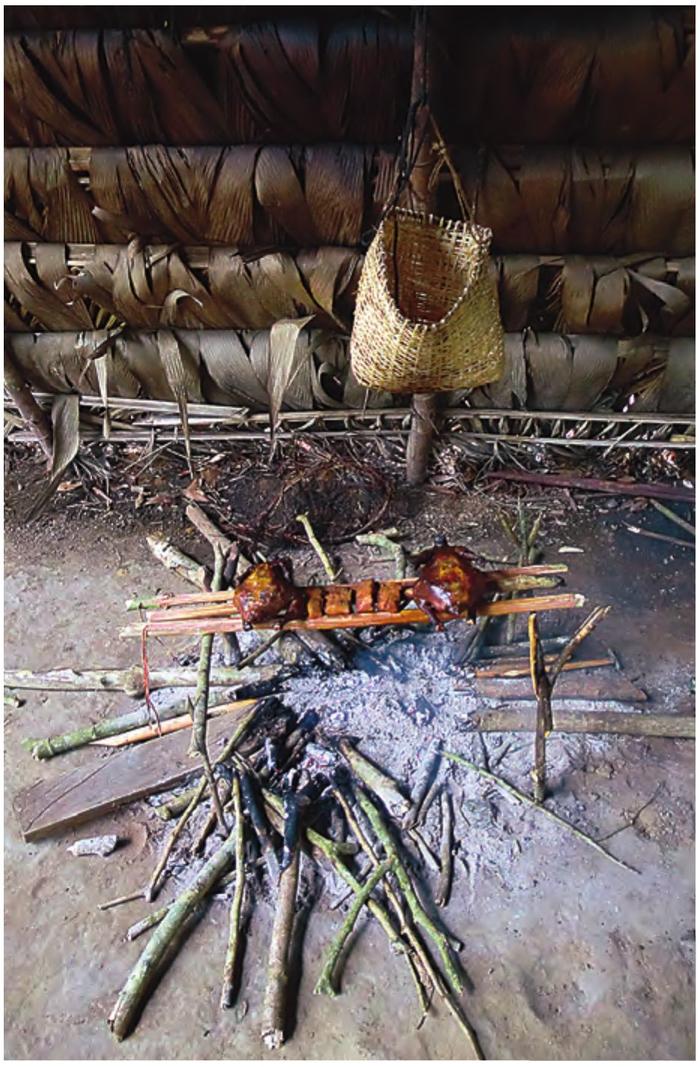

As my time with the Huaorani wore on, stocks from the outside world dwindled. This smoked chicken would be my last familiar meat and soon I was sampling paca (a long-legged forest relative of the guinea pig) among other new treats.

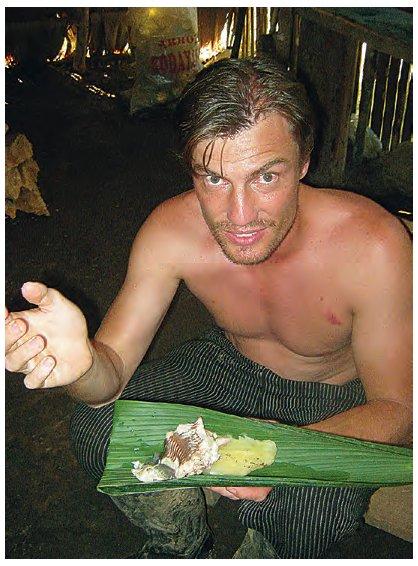

This fish and cassava would have been delicious on any other day, but a mystery lurgy laid me low and I almost offended my hosts by refusing it.

Omagewe’s wife (whose name I could never pronounce) made this loom in less than a minute, then wove me armbands, which included strands of Omagewe’s hair that he hacked from his head with a machete.