HTML The Definitive Guide (11 page)

Read HTML The Definitive Guide Online

Authors: Chuck Musciano Bill Kennedy

2.2 A First HTML Document

It seems every programming language book ever written starts off with a simple example on how to display the message, "Hello, World!" Well, you won't see a "Hello, World!" example in this book.

After all, this is a style guide for the next millennium. Instead, ours sends greetings to the World Wide Web:

My first HTML document Hello, World Wide Web!

Greetings from

Composed with care by:

(insert your name here)

©2000 and beyond

Go ahead: Type in the example HTML source on a fresh word-processing page and save it on your local disk as

myfirst.html

. Make sure you select to save it in ASCII format; word processor-specific file formats like Microsoft Word's

.doc

files save hidden characters that can confuse the browser software and disrupt your HTML document's display.

After saving

myfirst.html

(or

myfirst.htm

if you are using a DOS-or Windows 3.11-based computer) onto disk, start up your browser, locate, and then open the document from the program's File menu.

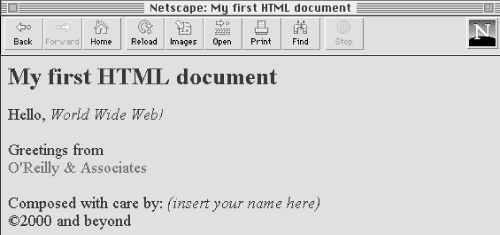

Your screen should look like

Figure 2.1

.

Figure 2.1: A very simple HTML document

2.1 Writing Tools

2.3 HTML Embedded Tags

2.3 HTML Embedded Tags

You probably have noticed right away, perhaps in surprise, that the browser displays less than half of the example source text. Closer inspection of the source reveals that what's missing is everything that's bracketed inside a pair of less-than (<) and greater-than (>) characters.

[The Syntax of a Tag,

HTML is an embedded language: you insert the language's directions or

tags

into the same document that you and your readers load into a browser to view. The browser uses the information inside the HTML tags to decide how to display or otherwise treat the subsequent contents of your HTML

document.

For instance, the tag that follows the word "Hello" in the simple example tells the browser to

display the following text in italic.[1]

[Physical Style Tags, 4.5]

[1] Italicized text is a very simple example and one that most browsers, except the text-only variety like Lynx, can handle. In general, the browser tries to do as it is told, but as we demonstrate in upcoming chapters, browsers vary from computer to computer and from user to user, as do the fonts that are available and selected by the user for viewing HTML documents. Assume that not all are capable or willing to display your HTML

document exactly as it appears on your screen.

The first word in a tag is its formal name, which usually is fairly descriptive of its function, too. Any additional words in a tag are special

attributes

, sometimes with an associated value after an equal sign (=), which further define or modify the tag's actions.

2.3.1 Start and End Tags

Most tags define and affect a discrete region of your HTML document. The region begins where the tag and its attributes first appear in the source document (also called the

start tag

) and continues until a corresponding

end tag

. An end tag is the start tag's name preceded by a forward slash (/ ). For example, the end tag that matches the "start italicizing" tag is .

End tags never include attributes. Most tags, but not all, have an end tag. And, to make life a bit easier for HTML authors, the browser software often infers an end tag from surrounding and obvious context, so you needn't explicitly include some end tags in your source HTML document. (We tell you which are optional and which are never omitted when we describe each tag in later chapters.) Our simple example is missing an end tag that is so commonly inferred and hence not included in the source that many veteran HTML authors don't even know that it exists. Which one?