I Am Abraham (37 page)

He must have had spies in the President’s House who read my every scratch. I was thinking hard on “a declaration of radical views,” much more

radical

than he might have imagined. I couldn’t crush Mr. Jeff without disinheriting him of his army of slaves.

“Mr. President, I may be on the brink of eternity, with all my warriors, so I can allow myself a little bluntness. You will require a Commander-in-Chief of the Army, one who possesses your confidences.” He paused to cup his chin in his hand. “I don’t ask that position for myself, but I am willing to serve in such position as you may assign me.”

He was a master of finesse, like an aeronaut in his balloon, surveying every corner of the landscape, but he forgot that I was holding the tether cords and could rein him in.

“Mr. McClellan,” I said, “I shan’t be appointing any dictators this season.”

The parlor was poorly lit, and I watched his generals smolder as they moved in and out of the dark like shadow men. Seward had warned me not to tangle with Little Mac on his own territory, that his generals were capable of any kind of revolt. Was I supposed to hide from Little Mac at Harrison’s Landing, not come here at all? I’d wounded his vanity, a little. His mustache was quivering.

“And what if the country should demand it of you?” he asked in a contralto’s nervous pitch.

“Well, there’s one Commander-in-Chief, far as I can tell, and you’re looking at him.”

He was absent from that moment on, his face stark white in the shadows, while we supped on a rabbit stew prepared by his family, absent while we went on a midnight parade in front of his adoring

legions

, boys who would have done anything to touch Dan Webster’s flanks, and that’s why I kept him, even while he ran off the battlefield like some brat, because I didn’t have another general who could hold the heartbeat of entire regiments in his hand. And when we returned to the old red house, it was Lieutenant Colonel Haverstall who accompanied me up the stairs with a candle; I could feel the malice in the tread of his heels—how he would have loved to pitch me over the banister and into the dark ruin of the stairwell. I heard him sniffle as the staircase rocked under our feet like a decrepit cradle. He delivered me to my bedroom in one piece, lit the lantern on the bureau. But his body writhed with emotion, and went stiff, like some gigantic claw.

“You have maligned him, Mr. President. He’s the best darn general in the service.”

He bolted out of there with the candle in his fist, and the clump of his boots haunted my sleep like hammer blows on the head.

35.

Jackson & the Little General

H

E

CARRIED

HIS

Bible with him into battle. Stonewall Jackson suffered from dyspepsia and had to suck on lemons all the time. He rode a gelding, Little Sorrel, but wasn’t much of a sight on his chestnut horse, slumped down in a ragged tunic, like some old-clothes man, with the bill of his cap nearly blinding him—that’s how low it sat. His eyes went bad, and his orderly, whom the general had taught to read, now had to recite passages from the Bible, or that dyspeptic man in his ragged coat couldn’t fall asleep.

Yet he wasn’t dyspeptic on the battlefield. He crept behind our lines in late August and found a treasure at Manassas Junction—all our damn supplies were sittin’ in the sun. That deacon sat on Little Sorrel and watched his boys have a Bacchanal. They gorged themselves on lobster salad and rinsed their throats with Union champagne. They wove around in feather hats and crinolines that must have belonged to some Union general’s war wife. They battled over jars of pickled oysters. They guzzled whiskey until the deacon-general confiscated all the whiskey they had and broke bottle after bottle against the side of a railroad car. He took nothing for himself. But he allowed his boys to escape with

some

of the spoils. He burnt and blew up whatever remained until that railroad junction resembled a vast funeral pyre.

I could smell the smoke from my country cottage—I assumed it was a

signal

that Richmond was on fire. I should have reckoned it was the first sign of our ruination. Jackson decided he would have one more funeral pyre. His men snuck back into the woods—and John Pope, who led our brand-new Army of Virginia, started his attack, confident that reinforcements would arrive from McClellan, but Pope’s boys wouldn’t fight; they loved Little Mac—and McClellan’s relief corps was nowhere to be found. He wouldn’t budge from his new headquarters at Annapolis. His horses were going blind in the sun, he said. And Little Mac telegraphed the War Department: “We have to leave Pope to get out of this scrape & at once use all our means to make the Capital safe.”

Jackson was like some apocalypse in a ragged coat who could mow down all the men and matériel between Manassas Junction and the District while sitting on the back of Little Sorrel. Our citizens waited for his gelding to appear on Pennsylvania Avenue with all those marching madmen in crinolines and feather hats. Willard’s wouldn’t let in any

unfamiliar

guests. The hotel’s habitués had steak and onions for breakfast, pigs’ feet and gingerbread for lunch, and sat around the Willard’s curved bar with hatchets under their coats, waiting for the barbarians. Families carted their possessions around in wheelbarrows, not knowing where to run; I could see them move in narrowing circles near the canal—their barrows looked like beetles. Some fancy girls from Marble Alley stood on the Long Bridge with

Secesh

flags until marines from the Navy Yard carried them off to Old Capitol Prison. The B&O station on Jersey Avenue was packed with people who would have given a month’s wages for a railroad pass out of the District—they clambered aboard military trains and left their baggage at the depot, while wounded soldiers wandered the streets.

My Cabinet screamed for McClellan’s scalp, but I couldn’t pull commanders out of my hat. The Rebels had Stonewall Jackson and Little Sorrel. All we had was Little Mac, who built encampments like a pharaoh, entombed himself, and never sought the muck of battle, but his men didn’t have much morale without him.

In early September, in a torrent of rain, as the last of Pope’s troops trudged back to the District, some of them without shirts or shoes, others limping in paper boots, Tad and I walked out the White House to greet them with a basket of little cakes. The soldiers moved in some kind of reveille, as if they couldn’t rouse themselves from the dream of battle. Their mouths twitched; their eyes fluttered to some private tune where pomp and circumstance failed to matter. They clutched the soggy cake and saluted Tad. He wasn’t a 3

rd

Lieutenant now, the pampered son of a President. The rain had lent him the illusion of a real officer, who just happened to look like a child.

“Greetings, sir. God protect ye.”

These soldiers saw something else in that torrent—

their

general, Little Mac, riding his black stallion through the blinding rain. These men couldn’t have mistaken him for Stonewall Jackson and his sorrel. He didn’t have tattered sleeves or a cap over one eye. He wore his full dress uniform, with a commander’s yellow sash. But the sash seemed much darker in the rain. He wasn’t some cockerel preening for his generals. His pain was much too raw; the horror seemed imbedded in his brow. His hand shook for a moment; and then this cautious, calculating general rode along that ragged line on Dan Webster and saluted every soldier with his cap. I watched him lean over the bridle and converse with a particular man, ask about his wife and children—it was hard to talk with rain in his mouth, but he swallowed the rain and didn’t cough once.

He removed his cape like some cavalier and put it around a shivering soldier. The soldier started to cry.

“I can’t take that, sir. It’s much too precious.”

“Son, it won’t get lost. You’ll know where to find me. Keep it as long as you like.”

Little Mac remained there until that line thinned out to nothing. Then he cantered over to me and Tad. He saluted my boy with that same wet cap.

“Lieutenant Lincoln,” he said, “I might need a bugler one of these days.”

“But I can’t bugle, sir.”

“Your

Paw

will learn ye,” he said in my Kentucky accent. He wasn’t mocking me. He was trying to play with my boy.

The pity was now gone from his eyes. McClellan was furious with me and my Cabinet. We had interfered with his notions of war. He didn’t believe much in willful ruin. He would have sat outside Richmond forever with his siege guns until the Rebels swallowed their own hides. War had little to do with chaos—it was, according to him, a contest between Christian generals, a dance as particular and patterned as the quadrille. But there were no ladies involved, just generals and their Christian soldiers. And he didn’t leave much room for Presidents and other civilians in this scrape. I was supposed to provide him with men and matériel and hold my tongue, while the Christian generals danced their quadrille in some far corner of the map. But he knew I would never buy that ticket. So he bent in his saddle, bowed to me, and rode off without another word, his stallion taking perfect steps as the rain lashed and lashed.

A

BITTER

WIND

SWIRLED

around the Soldiers’ Home. Mary caught a chill; Tad shivered in his nightshirt. And one afternoon, in mid-November of ’62, we abandoned our summer cottage, and with our cavalry escort right behind us, we moved back into the President’s House. It felt like an army of our own, all that crashing around in the dust.

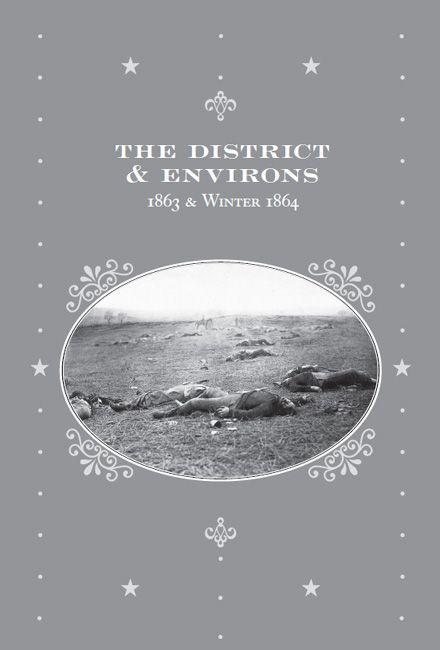

That same army crept inside my skull, as it strove in the corn. I’d landed in some Inferno where a great battle was fought over and over again. Cavalry from both sides charged about, beheading stalks. At first I thought it was a kind of brilliant exercise, that this cornfield was a training ground for cavalrymen. Then they whirled about and attacked their own horses. And the horses neighed with a horrible melody that carried across the field like the cries of children.

Bodies rose up from the crushed corn. It wasn’t much of a resurrection. They wandered about amid the blades of corn. And it didn’t seem to matter how hard I wept. I couldn’t save these wanderers. Then someone else rose out of the corn, a bugler with Willie’s light hair. He had blood all over his face, but I could recognize my own dead boy. I must have been right there with him, in that field of carnage, since he said, “

Paw

, do you miss me,

Paw

?”

I was confused and filled with every sort of wonder. I had no philosophy to deal with this, nothing I could ask my Maker about—if we had a Maker and hadn’t come out of a broth of little devils. Had heaven and hell swirled into one during the rebellion, and was war itself a spiritualist’s dream? Summerland had become a battleground of corn, with ambulances and bloated horses, and with my dead boy as a bugler—without his bugle.

And that’s when I saw him, the far rider with a Bible in his saddlebags. But he didn’t have his sorrel with him. He was struggling in the corn, his bony knees rising up and disappearing again. He could have had some piston in his back—that’s how regular was the rise and fall of his knees. He plucked his Bible out of a pocket, and he read from Revelation, as his knees rose and plunged.

And I saw heaven opened, and behold a white horse; and he that sat upon him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he doth judge and make war.

He was a horseless rider, a prophet in a rumpled coat, who sang about the white horse of war. All the wanderers were gone—and my Willie. The prophet was alone with his Bible and straggly black beard. He didn’t have his army of fanatics in their crinolines and feather hats, boys who went to war with their frying pans lodged inside their muskets, so they would have more room for gunpowder in their haversacks. He must have been a lunatic, because he danced and sang in the corn without the least bit of shame.

I heard the voice of harpers harping with their harps . . .

The bloated horses were gone, the cadavers with clamped fists and startled eyes, the ambulances with missing wheels, the haversacks, the muskets, the frying pans, as if that white horse had swept through the cornfield and wiped out the carnage in its wake. The prophet kept pumping with his knees, and it wasn’t madness at all. He was communing with the dead. And I realized what that rising and plunging meant. He was his own sorrel, horse and rider in the crushed corn.