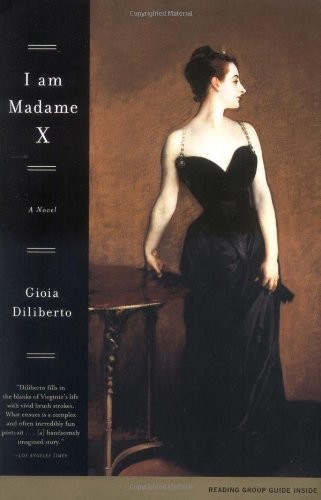

I Am Madame X

A Useful Woman: The Early Life of Jane Addams

Hadley

Debutante: The Story of Brenda Frazier

A LISA DREW BOOK/SCRIBNER

A LISA DREW BOOK/SCRIBNER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Any reference to historical events, real people, or real locales is used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2003 by Gioia Diliberto

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SCRIBNER

and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work.

A LISA DREW BOOK

is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Set in American Garamond

Designed by Colin Joh

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diliberto, Gioia, 1950–

I am Madame X: a novel / Gioia Diliberto

p. cm.

“A Lisa Drew book.”

1. Gautreau, Virginie Avegno, 1859–1915—Fiction. 2. Sargent, John Singer, 1856–1925—Fiction. 3. Americans—France—Fiction. 4. Portrait painting—Fiction. 5. Paris (France)—Fiction. 6. Socialites—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3604.I45 I12 2003

813’.54—dc21 2002026802

ISBN 0-7432-4566-0

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Joe Babcock

New York, 1915

Perhaps you’ve heard her name, Virginie Gautreau. You recall it like an old melody echoing yet from a long-ago party, or as a kind of epithet whispered harshly under the breath. Maybe you’ve even seen her picture—seen

the

picture. God knows, there are a few out there who truly have, though once all Paris claimed to have viewed it and recoiled at the insolence, the vulgarity, the unmuted sex. “Monstrous,” one critic said. “A singular failure,” sniffed another. John Singer Sargent’s career nearly derailed, though he’s famous now, living in England and making a fortune painting bored aristocrats.

He kept the picture in his studio for twenty years, exhibiting it only a handful of times, always in small shows in Europe. Until last year, I thought no one in America would ever see it. Then I heard that Sargent was sending the picture to San Francisco for the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition. I was in Paris on business, so I called Virginie with the news.

We had first met at a party in 1880, when I was a junior curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and traveled frequently to Paris. For several years, we dined together whenever I was in town; then we lost touch. When I reached Virginie on the telephone, she seemed delighted to hear from me, and she invited me to tea the next day at 123, rue la Cour, where she was living alone in a grand eighteenth-century apartment.

I arrived at four, as a soft afternoon light filtered through the tops of the chestnut trees. A young maid answered the bell and showed me into a huge parlor with tall windows facing the street. Several groupings of settees and chairs were arranged on an immense Turkish carpet, and four sparkling crystal chandeliers illuminated the room.

Virginie kept me waiting, as she always used to. She appeared after twenty minutes, wearing a green silk dress that matched her eyes, and her auburn hair—the same exact shade of burnished copper it had always been—was twisted into a long roll at the back of her head, her signature style. Though her figure had become matronly, her finely lined faced was still beautiful.

As she made her entrance, walking gracefully on high heels, whiffs of perfume preceding her, I was studying a picture on the wall—a sketch Sargent had made of her in the gorgeous black gown she had worn for her notorious portrait.

“Richard, my dear,” she said. She embraced me with long white arms and kissed me quickly and chastely on both cheeks. She had noticed me staring at the sketch, and she tilted her head toward it. “I don’t think I’ve seen you since—then.”

I’m sure she was thinking back, as I was, to 1884 and the jeering crowds at the Palais de l’Industrie. It was the opening of the Paris Fine Arts Salon, an annual exhibition that was the premier social event of the era. To have a portrait championed at the Salon usually meant instant success for the artist and overnight fame for the sitter. Sargent, an American who had been raised abroad, had begun to establish a name for himself in Parisian art circles, and he had high hopes that his painting of Virginie would push him to the top.

At the time, she was one of the most famous women in Paris. A favorite ornament of the scandal sheets, Virginie flaunted her sexuality through exotic makeup, hennaed hair, and revealing clothes. She penciled her eyebrows, rouged her ears, and dusted her skin with

blanc de perle

powder. To whiten it further, people murmured, she ingested arsenic.

Sargent’s portrait brilliantly captured her wanton sensuality. But it was too far in advance of its time. Instead of admiring the artist’s achievement, the public was appalled by it. The portrait seemed to confirm French prejudices against Americans, proved that we were pushy, overeager, lacking any limits or refinement.

Like Sargent, Virginie was widely known to be American. She had been born in New Orleans to two of Louisiana’s finest Creole families. During the Civil War, her mother had fled Louisiana, taking Virginie, who was a child, and her baby sister. The family settled in Paris in a Right Bank enclave of expatriate Southerners. Trading on their French ancestry and knowledge of French culture, they hoped to insinuate themselves into French society.

Virginie’s looks and charm were her tickets into the haut monde. She was trained from the cradle to make a brilliant marriage. She preferred to make a brilliant show, and she never lost her ardor for dangerous liaisons. The day I had tea with her, she was expecting a new lover, a married lawyer named Henri Beauquesne, whom she had recently met on a train. He was handsome and rich, she told me, and nearly twenty years her junior.

I still think Sargent’s portrait of Virginie was his best painting, and I told her so that day. “You know, I’d love to have it for the Metropolitan, Mimi,” I said, using her nickname.

“Make Sargent a generous offer, and maybe you can,” she said brightly as a maid wheeled in a cart holding a silver tea service and a plate of small fruit tarts. Virginie poured our tea into two gold-rimmed Limoges cups.

“Darling,” I told her, “Edward Robinson, the head of the Met, has been after it for years, ever since he worked at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. But so far, Sargent has refused to sell. He’s hardly let it out of his house. When he does exhibit it, he never identifies you. He still calls it

Portrait of Madame ***,

just as it was titled at the Salon, or simply,

Portrait.

And he always requests that your name not be communicated to the newspapers. Isn’t that amusing?”

Virginie wasn’t amused at all. In fact, she was furious. “Don’t I have a name?” she cried, rising out of her chair. She strode across the room to a wall of windows and pivoted to face me. “If Sargent had any honor, he would call my picture

Portrait of Virginie Avegno Gautreau.

After all, it is

my

picture as much as his.”

She stared fiercely at me. “This was

not

a commissioned work,” she continued, more composed. “Sargent begged me to sit for him. He stalked me like a hunter does a deer, staring at me at parties and getting his friends to pester me—‘Please, Madame Gautreau, let John pay this homage to your great beauty.’ And so on. That so-called artist Ralph Curtis came to see me, then bombarded me with letters. I saved one.”

She marched to an antique secretary, rummaged through a drawer, and pulled out a blue envelope. “My dear Madame Gautreau,” she read from the letter inside. “We both know John is a genius. But the work he’s done so far is somehow lacking in completeness and depth. He needs a great subject to unleash the full power of his brilliance. He needs you.”

She folded the letter and returned it to the envelope. “I was the one who sat for hours on end, giving up an entire summer. I was the one who provided the magnificent profile, the willowy body, the white marble skin that ‘unleashed his brilliance.’ I was the inspiration for Sargent’s masterpiece—the only one he’s got.” She tossed her head dismissively, provocatively, the way I had seen her do so many years ago. “Just compare my portrait with his stuffy pictures of horsey Englishwomen. Or that midget Mrs. Carl Meyer or that washed-out blonde, Mrs. George Swinton. I’ve seen their portraits and plenty of others over the years. I’ve kept my eye on Sargent’s exhibits, and I want to ask you: Where are the bold lines in those pictures? Where is the mystery, the tension, the allure?” She dropped into a chair covered with cream damask and folded her arms across her chest. “Of course, I know exactly why Sargent won’t attach my name to the portrait. He’s a cowardly fussbudget, and he’s still livid about the ruckus my mother made.”

Obviously, the trauma of the Salon debacle still pained her. Seeing her now, her beauty turning brittle, her natural hauteur hardened into a lonely defensiveness, I could see how she had mourned the loss of her renown, and I felt shamed that I had stopped calling on her so many years before.

We chatted for several more hours, and the golden light outside the tall French windows fell to darkness. At eight, I rose to leave, but Virginie urged me to stay. “Please have dinner with Henri and me,” she said, her eyes shining. I was curious to meet Beauquesne, her new young lover, but I had already made plans with friends.

“Mimi, it’s been wonderful to see you again; now I must run,” I said. She showed me to the door and kissed me again on both cheeks. “Good-bye, Richard, my dear. You’ve brought back so many memories.”

I heard nothing from her for months. Then one day she sent me a package containing several hundred typed pages. Inspired by my visit, she had dictated a memoir to one of her maids. She wanted history to remember who Madame X was.

Two weeks later, before I had done more than glance at the manuscript, I got a transatlantic cable from Beauquesne. Virginie had died in her sleep. He hoped that I still had her memoir, as it was the only copy, and he wondered if I would help him find a publisher for it.

Thus, I make her story available here, in my own translation from the original French. As you read it, you will be lifted back to a time before this terrible war, a time when painting was a powerful indice of reality, and Virginie Gautreau was, as

Le Figaro

once put it, “a living work of art.”

I can still see her as she looked then, on the night I first met her. She was tall and slim, her green eyes glittering in that porcelain face, and her silvery laughter floating across the table as she reached for a champagne flute with a long, shapely arm.

How could anyone forget?

Richard Merriweather

Curator of American Painting

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York, 1915