I, Fatty (34 page)

Authors: Jerry Stahl

But I was talking about slander. After one year. After five years. After 10. The burn of those words had not let up a single degree. I found ways not to visit them, but their heat was there. Like a boiler in the basement, going full-tilt even in summertime.

I can hear you groaning. Fatty Arbuckle, going philosophical? It's like the old Professor Pork Act, where the pig puts on a tux, then stands on two legs and does geometry.

After my little attack in the middle of

In the Dough,

I struggled wobbly to my feet and blinked. Jack Henley, the director, took one look at me and made the decision. "Let's call it a day."

I told Henley, "No dice, we keep going!" And so we kept shooting. The film was due that day, and by God, I'd make sure it was finished. See, this was my chance to get everything back. But—like you always hear people say—by the time I got what I wanted, I realized how little I really wanted it. And anyhow, what was anything a fat man accomplished worth? There seemed little doubt that I would become beloved again. But this time, I'd know it meant nothing. It was a bitter kind of happiness.

That same night, on the 28th—a week late—Addie and I celebrated our one-year anniversary. That very day, word had come down from on high, I'd be back making features next year. Warner was talking talkies. The contract was being drawn up. Maybe, I thought, everything would be returned to me, like the swallows to Capistrano. But what did that matter, once you knew the things were just going to fly away again?

Addie walked down Fifth Avenue and I held her hand and I looked up at the stars and I felt . . . nothing. But not in a bad way.

We went up to our rambling apartment. Gazed at the trees silhouetted by the streetlight. I felt so happy at that moment it was almost crummy. Because everything was so perfect. But I'd had perfect happiness before, more or less, and look what happened . . . The trouble with everything was how suddenly it could turn to nothing. Every Baby Ruth a toothache in a fancy wrapper. So this is what I did: I told Addie I loved her and wanted to hit the hay. She asked if she could undress me, and I said sure. We did that sometimes. Addie took off my clothes and ran me a bath. I called her my geisha girl, since I'd known a few of those in my

Mikado

days.

This is when Addie announced that she had something special she wanted to wear. But she insisted that she wait until after I came out of the bath before showing me. I told her, "Fine, dear." No longer even lamenting my lack of feeling. Life could be just as pleasant without feeling anything. I was going to be a star again. That was enough. Even if I wouldn't feel any differently, at least the world would be right again. And what was that worth?

I lay back in the tub. Closed my eyes. So this is what Job got in the end, I thought, with something like relief. Everything he lost came back—except the delusion that it was really his, and the belief that it mattered.

And then a voice I recognized, but couldn't,

wouldn't

let myself acknowledge, spoke right at me. Daddy again. Why wouldn't the old juicehead stay dead?

Well, bully, for you, Fat Boy. You got just what you wanted. Think that makes you special? Don't kid yourself, potato sack, it don't . . .

And in a flickering, like one frame of a two-reeler, I saw the old man standing there. Ragged as the clothes he was buried in, floating in front of the tub. Out of habit, I checked to see if he was holding a belt.

You know what you got? You got to keep your big rump roast out of the gas oven. That's what you got, Daddy said. And that's all you got.

I made the decision to get up and get the needle right there, and commenced to fix myself an arm cocktail on the spot. Same old heroin the folks at Bayer used to peddle. Okie had a pal in the warehouse. He'd slipped me enough for a weeks' supply.

I fired the whole tube and felt my toes uncurl. I never knew they were curled until I took a shot and I uncurled them. The bubble of dread in my heart whispered

P-O-P!

Red warmth flooded my eyes. The smallest breath of air became a solid thing, nearly too heavy to lift. But that was all right. I didn't need much air. Just enough to hoist my haunches out of the tub.

I toddled out of the bathroom, naked and dripping, and shuffled my last few steps to the window overlooking the park. Let my gaze rest on the dark under the trees.

Now I feel some peace. It's too much, getting everything back. The strain of maybe losing it again and again makes it ashes in my piehole. I would have lived with a crick in my neck from looking over my shoulder, waiting for Calamity Jane to ride up and shoot a message in my fat and mortal ass one more time.

No, sir. It's easier this way. Easier to gaze out the window, into trees and darkness. I ask you again, what was anything a fat man accomplished? A pile of leaves waiting for a wind.

I've been dodging the hook since I was 10. I'm out of somersaults.

Write this down.

St. Francis Hotel, Room 1221

San Francisco

2003

American Silent Film.

William K. Everson. New York: Da Capo Press, 1978 (reprint).

American Silent Film: Discovering Marginalized Voices.

Gregg Bachman and Thomas J. Slater, eds. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University, 2002.

American Weekly.

"Love, Laughter and Tears: The Hollywood Story." Adela Rogers St. Johns. Oct. 22, 1950.

A-Z of Silent Film Comedy: An Illustrated Companion.

Glenn Mitchell. London: B. T. Batsford, 1998.

Behind the Mask of Innocence: Sex, Violence, Prejudice, Crime

—

Films of Social Conscience in the Silent Era.

Kevin Brownlow. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

California Babylon: A Guide to Sites of Scandal, Mayhem, and Celluloid in the Golden State.

Kristan Lawson and Anneli Rufus. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2000.

Cocaine Fiends and Reefer Madness: An Illustrated History of Drugs in Movies.

Michael Starks. New York: Cornwall Books, 1982.

Comedy Is a Man in Trouble: Slapstick in American Movies.

Alan Dale. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

The Comic Mind: Comedy and the Movies.

Gerald Mast. Indianapolis: Bobbs- Merrill, 1973.

The Day the Laughter Stopped.

David A. Yallop. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1976.

An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915-1928.

History of American Cinema, Vol. 3. Richard Koszarski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Frame-Up! The Untold Story of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle.

Andy Edmonds. New York: William Morrow, 1991.

The Grove Book of Hollywood.

Christopher Silvester, ed. New York: Grove Press, 1998.

Hearst over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propaganda in the Movies.

Louis Pizzitola. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams: A History of America's Romance with Illegal Drugs.

Jill Jonnes. New York: Scribner's, 1996.

Hollywood Babylon.

Kenneth Anger. New York: Dell, 1975.

Hollywood Death and Scandal Sites.

E. J. Fleming. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000.

Hollywood Remembered: An Oral History of Its Golden Age.

Paul Zollo. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002.

Hollywood Studio.

"The Early Years of Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle." Frank Taylor. June 1971.

Inventing the Dream: California Through the Progressive Era.

Kevin Starr. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

The Keystone Kid: Tales of Early Hollywood.

Coy Watson Jr. Santa Monica: Santa Monica Press, 2001.

Letter to Adolph Zukor and Joseph Lasky. Arthur Hammerstein. Dec. 26, 1922. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

Letter to Adolph Zukor. William Hays. Dec. 1921. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

Letter to Adolph Zukor. William Hays. Dec. 25,1921. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

Letter to Adolph Zukor. William Hays. Sept. 5, 1922. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

Letter to Joseph Lasky. Roscoe C. Arbuckle. Oct. 1, 1921. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

Mabel.

Betty Harper Fussell. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1982.

Motion Picture World.

"'Fatty' Arbuckle Allied with Paramount." Jan. 27, 1917.

Moving Picture World.

"Hays Suspends 'Fatty' Arbuckle Films." April 29, 1922.

National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. "The Return of Arbuckle to the Screen." Dec. 23, 1922. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Beverly Hills.

The New Biographical Dictionary of Film.

David Thomson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

New York Sun.

"Fatty Arbuckle Dies in Sleep." June 29, 1933.

New York Times.

"Testifies Arbuckle Admitted Attack." Sept. 22, 1921.

New York Times.

"Testify to Bruises on Virginia Rappe." Sept. 23, 1921.

New York Times.

"Semnacher Tells of Arbuckle Party." Sept. 24, 1921.

New York Times.

"Women Testify Today in Arbuckle Case." Sept. 26, 1921.

New York Times.

"Charges Blackmail at Arbuckle Trial." Sept. 27, 1921.

New York Times.

"Prosecution Rests in Arbuckle Case." Sept. 28, 1921.

New York Times.

"Arbuckle on Bail for Manslaughter." Sept. 29, 1921.

New York Times.

"Fatty Arbuckle Comes Back with Pardon from Hays." Dec. 20, 1922.

New York Times.

"Fatty Gets Big Ovation at Pantages Debut." June 7, 1924.

"Nobody Loves a Fat Man." Minta Durfee Arbuckle. Unpublished, 1953.

The Parade's Gone By . . .

Kevin Brownlow. 1968. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996 (reprint).

"Personal Impressions of the Famous Trial." Rev. James L. Gordon. 1922.

Photoplay Magazine.

"Heavyweight Athletics." K. Owen. April 1915.

Photoplay Magazine.

"Love Confessions of a Fat Man." Roscoe Arbuckle, as told to Adela Rogers St. John.

Photoplay Magazine.

"Speaking of Pictures." James R. Quirk. August 1925.

Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle: A Biography of the Silent Film Comedian, 1887-1933.

Stuart Oderman. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1994.

The Silent Clowns.

Walter Kerr. New York: Da Capo Press, 1990 (reprint).

Silent Stars.

Jeanine Basinger. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

This Is Hollywood: An Unusual Movieland Guide.

Ken Schessler. Redlands, California: Ken Schessler Publishing, 1978.

The Timetables of History.

Laurence Urdang, ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981.

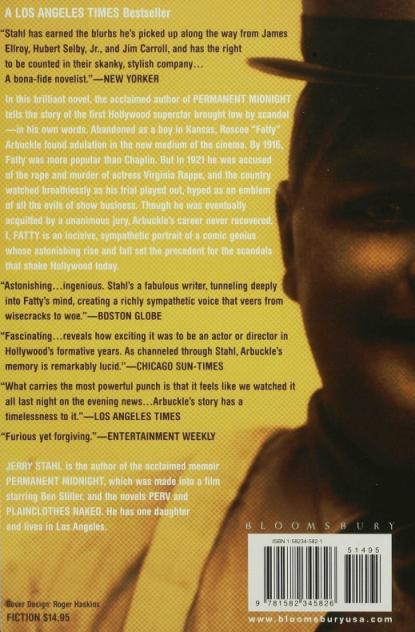

Jerry Stahl is the author of the bestselling memoir

Permanent Midnight

and the novels

Perv

—

A Love Story

and

Plainclothes Naked.

He has one daughter and lives in Los Angeles.

The text of this book is set in Linotype Sabon, named after the type founder, Jacques Sabon. It was designed by Jan Tschichold and jointly developed by Linotype, Monotype, and Stempel in response to a need for a typeface to be available in identical form for mechanical hot metal composition and hand composition using foundry type.

Tschichold based his design for Sabon roman on a font engraved by Garamond, and Sabon italic on a font by Granjon. It was first used in 1966 and has proved an enduring modern classic.