I Have Landed (15 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

I have thus grown to appreciate Sullivan more and more over the years, but I still lean to the view, probably held by a majority of Savoyards, that Gilbert's text must be counted as more essential to their joint survival. (Gilbert might have found another collaborator of passable talent, though no one could match Sullivan, but Sir Arthur would surely have gone the way of Victor Herbert, despite his maximal musical quality, without Gilbert's texts.) My Swiss moments with Gilbert therefore bring me even greater pleasure, make me wonder how much we have all missed, and lead me to honor, even more, the talent of a man who could so love his vernacular art, while not debasing or demeaning these accomplishments one whit by festooning the texts with so many gestures and complexities that few may grasp, but that never interfere with the vernacular flow. Gilbert thus surpasses Jack Point, his own jester in

Yeomen of the Guard

, by simultaneous expression of his two levels:

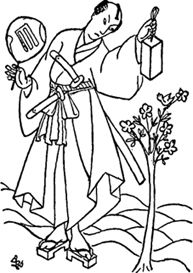

Jack Point, Gilbert's jester, showing “a grain or two of truth among the chaff” of his humor

.

I've jibe and joke

And quip and crank

For lowly folk

And men of rank. . .

I can teach you with a quip, if I've a mind

I can trick you into learning with a laugh;

Oh, winnow all my folly, and you'll find

A grain or two of truth among the chaff!

As a small example of Gilbert's structural care, I don't know how many hundred times I have heard the duet between Captain Corcoran and Little Buttercup at the beginning

of Pinafore's

Act II. Buttercup hints at a secret that, when revealed, will fundamentally change the Captain's status. (We later learn, in the classic example of Gilbertian topsy-turvy, that Buttercup, as the captain's nursemaid “a many years ago,” accidentally switched him with another baby in her chargeâwho just happens to be none other than Ralph Rackstraw, now

revealed as nobly born, and therefore fit to marry the Captain's [now demoted] daughter after all.) The song, as I knew even from day one at age ten, presents a list of rhyming proverbs shrouded in mystery. But I never discerned the textual structure until my Swiss moment just a few months ago. (I do not, by the way, claim that this text displays any great profundity. I merely point out that Gilbert consistently applies such keen and careful intelligence to his efforts, even when most consumers may not be listening. One must work, after all, primarily for one's own self-respect.)

I suppose I always recognized that Buttercup's proverbs all refer to masquerades and changes of status, as she hints to the Captain:

Black sheep dwell in every fold;

All that glitters is not gold;

Storks turn out to be but logs;

Bulls are but inflated frogs.

But I never grasped the structure of Captain Corcoran's response. He admits right up front that Buttercup's warnings confuse him: “I don't see at what you're driving, mystic lady.” He then parries her proverbizing, supposedly in kind, at least according to his understanding:

Though I'm anything but clever,

I could talk like that forever.

Gilbert's simple device expresses the consummate craftsmanship, and the unvarying intelligence, that pervades the details of all his texts. The captain also pairs his proverbs in rhymed couplets. But each of his pairs includes two proverbs of opposite import, thus intensifying, by the song's structure, the character of the captain's befuddlement:

Once a cat was killed by care;

Only brave deserve the fair.

Wink is often good as nod;

Spoils the child who spares the rod.

(Just to be sure that I had not experienced unique opacity during all these years of incomprehension, I asked three other friends of high intelligence and good Gilbertian knowledgeâand not a one had ever recognized the structure behind the Captain's puzzlement.)

The Captain of the Pinafore hears Little Buttercup's rhymed warnings with puzzlement

.

To cite one more example of Gilbert's structural care and complexity, the finale to Act I of

Ruddigore

begins with three verses, each sung by a different group of characters with varied feelings about unfolding events. (In this Gilbertian parody of theatrical melodrama, Robin Oakapple has just been exposed as the infamous Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet of Ruddigore, condemned by a witch's curse to commit at least one crime each day. This exposure frees his younger brother, Despard, who had borne the title and curse while his big brother lived on the lam, but who may now reform to a desired life of calm virtue. Meanwhile, Richard Dauntless, Ruthven's foster brother and betrayer, wins the object of his dastardly deed, the jointly beloved Rose Maybud.)

Each of the three groups proclaims happiness surpassing a set of metaphorical comparisons. But I had never dissected the structure of Gilbert's imagery, and one verse had left me entirely confusedâuntil another Swiss moment at a recent performance. The eager young lovers, Richard and Rose, just united by Richard's betrayal, begin by proclaiming that their own joy surpasses several organic images of immediate fulfillment:

Oh happy the lily when kissed by the bee. . .

And happy the filly that neighs in her pride.

Despard and his lover, Margaret, now free to pursue their future virtue, then confess to happiness surpassing several natural examples of delayed gratification:

Oh, happy the flowers that blossom in June,

And happy the bowers that gain by the boon.

But the lines of the final group had simply puzzled me:

Oh, happy the blossom that blooms on the lea,

Likewise the opossum that sits on a tree.

Why cite a peculiar marsupial living far away in the Americas, except to cadge a rhyme? And what relevance to Ruddigore can a flower on a meadow represent? I resolved Gilbert's intent only when I looked up the technical definition of a leaâwhat do we city boys know?âand learned its application to an arable field temporarily sown with grass for grazing. Thus the verse cites two natural images of items far and uncomfortably out of placeâan irrelevant opossum in distant America, and a lone flower in a sea of grass. The three singers of this verse have all been cast adrift, or made superfluous, by actions beyond their controlâfor Hannah, Rose's aunt and caretaker, must now live alone; Zorah, who also fancied Richard, has lost her love; and Adam, Robin's good and faithful manservant, must now become the scheming accomplice of the criminalized and rechristened Ruthven.

Finally I recognized the structure of the entire finale as a progressive descent from immediate and sensual joy into miseryâfrom Rose and Richard's current raptures; to Despard and Margaret's future pleasures; to the revised status of Hannah, Zorah, and Adam as mere onlookers; to the final verse, sung by Ruthven alone, and proclaiming the wretchedness of his new criminal roleânot better than the stated images (as in all other verses), but worse:

Oh, wretched the debtor who's signing a deed!

And wretched the letter that no one can read!

For Ruthven only cites images of impotence, but he must become an

active

criminal:

But very much better their lot it must be

Than that of the person

I'm making this verse on

Whose head there's a curse onâ

Alluding to me!

Again, I claim no great profundity for Gilbert, but only the constant intelligence of his craftsmanship, and his consequent ability to surprise us with deft touches, previously unappreciated. In this case, moreover, we must compare Gilbert with the medieval cathedral builders who placed statues in rooftop positions visible only to God, and therefore not subject to any human discernment or approbation. For these verses rush by with such speed, within so dense an orchestral accompaniment, and surrounded by so much verbiage for the full chorus, that no one can hear all the words in any case. Hadn't Gilbert, after all, ended the patter trio in

Ruddigore's

second act by recognizing that all artists must, on occasion, puncture their own bubbles or perish in a bloat of pride?

This particularly rapid, unintelligible patter

Isn't generally heard, and if it is it doesn't matter.

Mr. Justice Stewart famously claimed, in true (if unintended) Gilbertian fashion, that he might not be able to define pornography, but that he surely knew the elusive product when he saw it. I don't know that we can reach any better consensus about the orthogonal, if not opposite, phenomenon of excellence, but my vernacular plane knows, while my limited insight into Plato's plane can only glimpse from afar (and through a dark glass), that Gilbert and Sullivan have passed through this particular gate of our mental construction, and that their current enthusiasts need never apologize for loving such apparent trifles, truly constructed as pearls beyond price.

Ko-Ko, reciting the tale of Titwillow to win Katisha and (literally) save his neck

.

Ko-Ko, to win Katisha's hand and save his own neck, weaved a tragically affecting tale about a little bird who drowned himself because blighted love has broken his heart. But Ko-Ko spun his entire storyâthe point of Gilbert's humor in Sullivan's wonderfully sentimental songâon the slightest of evidentiary webs, for the bird spoke but a single mysterious word, reiterated in each verse: “tit willow.” Even the most trifling materials in our panoply of forms can, in the right hands, be clothed in the magic of excellence.

Art Meets Science in

The Heart of the Andes:

Church Paints, Humboldt Dies, Darwin Writes, and Nature Blinks in the Fateful Year of 1859

T

HE

INTENSE EXCITEMENT AND FASCINATION THAT

Frederic Edwin Church's

Heart of the Andes

solicited when first exhibited in New York in 1859 may be attributed to the odd mixture of apparent opposites so characteristic of our distinctive American style of showmanshipâcommercialism and excellence, hoopla and incisive analysis. The large canvas, more than ten by five feet, and set in a massive frame, stood alone in a darkened room, with carefully controlled lighting and the walls draped in black.

Dried plants and other souvenirs that Church had collected in South America probably graced the room as well. Visitors marveled at the magisterial composition, with a background of the high Andes, blanketed in snow, and a foreground of detail so intricate and microscopically correct that Church might well be regarded as the Van Eyck of botany.

But public interest also veered from the sublime to the merely quantitative, as rumors circulated that an unprecedented sum of twenty thousand dollars had been paid for the painting (the actual figure of ten thousand dollars was impressive enough for the time). This tension of reasons for interest in Church's great canvases has never ceased. A catalog written to accompany a museum show of his great Arctic landscape,

The Icebergs

, contains, in order, as its first three pictures, a reproduction of the painting, a portrait of Church, and a photo of the auctioneer at Sotheby's gaveling the sale at $2.5 million as “the audience cheered at what is [or was in 1980, at the time of this sale] the highest figure ever registered at an art auction in the United States.”