I Have Landed (31 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Bauhin's taxonomy places a fossil snail shell next to an inorganic mass of crystals because both have roughly the same shape

.

2.

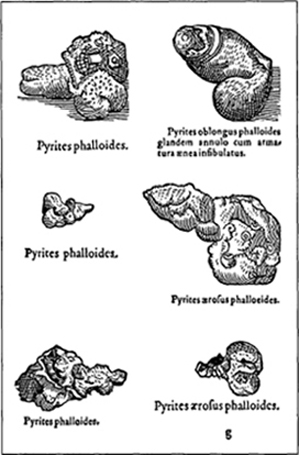

Failure to distinguish accidental resemblance from genuine embodiment

. Contrary to a common impression, Jean Bauhin and his contemporaries did not claim that all fossils must be inorganic in origin and that none could represent the petrified remains of former plants and animals. Rather, they failed to make a sharp taxonomic distinction between specimens that they did regard as organic remains and other rocks that struck them as curious or meaningful for their resemblance to organisms or human artifacts, even though they had presumably formed as inorganic products of the mineral kingdom. Thus, Bauhin includes an entire page of six rocks that resemble male genitalia, while another page features an aggregate of crystals with striking similarity in form to the helmet and head covering in a suit of armor. He does not regard the rocks as actual fossilized penises and testicles, and he certainly doesn't interpret the “helmet” as a shrunken trophy from the Battle of Agincourt. But his taxonomic juxtaposition of recognized mineral accidents with suspected organic remains does lump apples and oranges together (or, should I say, apples and pears, without a stem-up-or-down convention to permit a fruitful separation), thereby strongly impeding our ability to identify distinct causes and modes of origin for genuine fossil plants and animals.

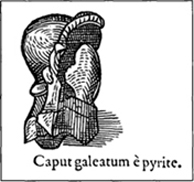

Bauhin's caption reads: “a helmeted head made of pyrite”

â

an accidental resemblance that he regarded as meaningful, at least in a symbolic sense

.

Bauhin's 1598 illustration of six rocks that resemble penises. He did not regard them as actual fossils of human parts, but he did interpret, as causally meaningful, a likeness that we now regard as accidental

.

3.

Drawing organic fossils with errors that preclude insight into their origins

. Bauhin claimed that he drew only what he saw with his eyes, unencumbered by theories about the nature of objects. We may applaud this ideal, but we must also recognize the practical impossibility of full realization. What can be more intricate and complex than a variegated rock filled with fossils (most in fragmentary condition), mineral grains, and sedimentary features of bedding followed by later cracking and fracturing? Accurate drawing requires that an artist embrace some kind of theory about the nature of these objects, if only to organize such a jumble of observations into something coherent enough to draw.

Since Bauhin did not properly interpret many of his objects as shells of ancient organisms that had grown bigger during their lifetimes, he drew several specimens with errors that, if accepted as literal representations, would have precluded their organic status. For example, he tried to represent the growth lines of a fossil clam, but he drew them as a series of concentric circlesâ

implying impossible growth from a point on the surface of one of the valvesârather than as a set of expanding shell margins radiating from a starting point at the edge of the shell where the two valves hinge together.

Bauhin also drew many ammonite shells fairly accurately, but these extinct relatives of the chambered nautilus grew with continually enlarging whorls (as the animal inside increased in size). Bauhin presents several of his ammonites, however, with a final whorl distinctly smaller than preceding volutions from a younger stage of growth. Reading this error literally, an observer would conclude that these shells could not have belonged to living and growing organisms. Finally, in the most telling example of all, Bauhin drew three belemnites (cylindrical internal shells of squidlike animals) in vertical orientation, covered with a layer of inorganic crystals on topâclearly implying that these objects grew inorganically, like stalactites hanging from the roof of a cave.

The final whorl of this fossil ammonite becomes smaller, showing that Bauhin did not recognize the object as a fossil organism whose shell would have increased in width during growth

.

Bauhin's most telling example of iconographic conventions that he established and that show his misunderstanding of the organic nature of fossils. He draws these three belemnites (internal shells of extinct squidlike animals) as if they were inorganic stalactites hanging down from the ceiling of a cave

.

Bauhin draws this fossil clam shell incorrectly, with growth lines as concentric circles. He did not recognize the object as the remains of an organism that could not grow in such a manner

.

So long as later scientists followed these three iconographic conventions that Bauhin developed in 1598, paleontology could not establish the key principle for a scientific understanding of life's history: a clear taxonomic separation of genuine organic remains from all the confusing inorganic objects that had once been lumped together with them into the heterogeneous category of “figured stones”âan overextended set of specimens far too diffuse in form, and far too disparate in origin, to yield any useful common explanations. These early conventions of drawing and classification persisted until the late eighteenth century, thus impeding our understanding about the age of the Earth and the history of life's changes. Even the word

fossil

did not achieve its modern restriction to organic remains until the early years of the nineteenth century.

I do not exhume this forgotten story to blame Jean Bauhin for establishing a tradition of drawing that made sense when naturalists did not understand the meaning of fossils and had not yet separated organic remains from mineral productionsâa tradition that soon ceased to provide an adequate framework and then acted as an impediment to more-productive taxonomies. The dead bear no responsibility for the failures of the living to correct their inevitable errors.

I would rather praise the Bauhin brothers for their greatest accomplishment in the subject of their primary joint expertiseâbotanical taxonomy. Brother Caspar of the bezoar stone published his greatest work,

Pinax

, in 1623âa taxonomic system for the names of some six thousand plants, representing forty years of his concentrated labor. Brother Jean of the fossils of Boll had been dead for thirty-seven years before his greatest work,

Historia plantarum universalis

, achieved posthumous publication in 1650, with even more elaborate descriptions and synonyms of 5,226 distinct kinds of plants.

Botanical taxonomy before the Bauhin brothers had generally followed capricious conventions of human convenience rather than attempting to determine any natural basis for resemblances among various forms of plants (several previous naturalists had simply listed the names of plants in alphabetical order). The Bauhin brothers dedicated themselves to the first truly systematic search

for a “natural” taxonomy based on principles of order intrinsic to plants themselves. (They would have interpreted this natural order as a record of God's creative intentions; we would offer a different explanation in terms of genealogical affinity produced by evolutionary change. But the value of simply deciding to search for a “natural” classification precedes and transcends the virtue of any subsequent attempt to unravel the causes of order.)

Caspar Bauhin may have slightly impeded the progress of bibliography by retaining an outmoded system in his bezoar book. Jean Bauhin may have stymied the development of paleontology in a more serious manner by establishing iconographic conventions that soon ceased to make sense but that later scientists retained for lack of courage or imagination. But the Bauhin brothers vastly superseded these less successful efforts with their brilliant work on the fruitful basis of botanical taxonomy. Their system, in fact, featured a close approach to the practice of binomial nomenclature, as later codified by Linnaeus in mid-eighteenth-century works that still serve as the basis for modern taxonomy of both plants and animals.

Science honored the Bauhin brothers when an early Linnaean botanist established

Bauhinia

as the name for a genus of tropical trees. Linnaeus himself then provided an ultimate accolade when he named a species of this genus

Bauhinia bijuga

, meaning “Bauhins linked together,” to honor the joint work of these two remarkable men. We might also recall Abraham Lincoln's famous words (from the same inaugural address that opened this essay) about filial linkage of a larger kindâbetween brethren now at war, who must somehow remember the “mystic chords of memory” and reestablish, someday, their former union on a higher plane of understanding.

The impediments of outmoded systems may sow frustration and discord, but if we force our minds to search for more fruitful arrangements and to challenge our propensity for passive acceptance of traditional thinking, then we may expand the realms of conceptual space by the most apparently humble, yet most markedly effective, intellectual device: the development of a new taxonomic scheme to break a mental logjam. “Rise up . . . and come away. For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth” (Song of Solomon 2:10â12)âfruits of nature for the Bauhin brothers, and all their followers, to classify and relish.