I Have Landed (37 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Ironically, Tsien's mice disprove these two fallacies of genetic determinism from within. By identifying their gene and charting the biochemical basis of its action, Tsien has demonstrated the value and necessity of environmental enrichment for yielding a beneficial effect. This gene doesn't make a mouse “smart” all by its biochemical self. Rather, the gene's action allows adult mice to retain a neural openness for learning that young mice naturally possess but then lose in aging.

Even if Tsien's gene exists, and maintains the same basic function in humans (a realistic possibility), we will need an extensive regimen of learning to potentiate any benefit from its enhanced action. In fact, we try very hardâoften without success, in part because false beliefs in genetic determinism discourage our effortsâto institute just such a regimen during a human lifetime. We call this regimen “education.” Perhaps Jesus expressed a good biological insight when he stated (Matthew 18:3), “Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.”

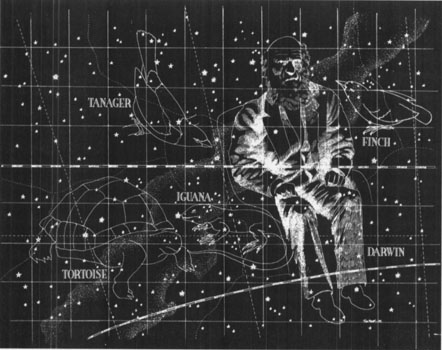

The Meaning and Drawing of Evolution

Â

Â

EFINING

AND

B

EGINNING

18

What Does the Dreaded “E” Word Mean Anyway?

E

VOLUTION

POSED

NO

TERRORS

IN

THE

LIBERAL

CON

stituency of New York City when I studied biology at Jamaica High School in 1956. But our textbooks didn't utter the word eitherâa legacy of the statutes that had brought William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow to legal blows at Tennessee's trial of John Scopes in 1925. The subject remained doubly hidden within my textbookâcovered only in chapter 63 of sixty-six, and described in euphemism as “the hypothesis of racial development.”

The anti-evolution laws of the Scopes era, passed during the early 1920s in several Southern states, remained on the books until 1968, when the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional. The laws were never strictly enforced, but their existence cast a pall over American education, as textbook publishers capitulated to produce “least common denominator” versions acceptable in all statesâso

schoolkids in New York got short shrift because the statutes of some distant states had labeled evolution as dangerous and unteachable.

Ironically, at the very end of the millennium (I wrote this essay in late November 1999), demotions, warnings, and anathemas have again come into vogue in several regions of our nation. The Kansas school board has reduced evolution, the central and unifying concept of the life sciences, to an optional subject within the state's biology curriculum (an educational ruling akin to stating that English will still be taught, but grammar may henceforth be regarded as a peripheral frill, permitted but not mandated as a classroom subject).

13

Two states now require that warning labels be pasted (literally) into all biology textbooks, alerting students that they might wish to consider alternatives to evolution (although no other well-documented scientific concept evokes similar caution). Finally, at least two states have retained their Darwinian material in official pamphlets and curricula, but have replaced the dreaded “E” word with a circumlocution, thus reviving the old strategy of my high school text.

As our fight for good (and politically untrammeled) public education in science must include the forceful defense of a key wordâfor inquisitors have always understood that an idea can be extinguished most effectively by suppressing all memory of a defining word or an inspirational personâwe might consider an interesting historical irony that, properly elucidated, might even aid our battle. We must not compromise

our

showcasing of the “E” word, for we give up the game before we start if we grant our opponents control over defining language. But we should also note that Darwin himself never used the word “evolution” in his epochal book of 1859, the

Origin of Species

, where he calls this fundamental biological process “descent with modification.” Darwin, needless to say, did not shun “evolution” for motives of fear, conciliation, or political savvyâbut rather for an opposite and principled reason that can help us to appreciate the depth of the intellectual revolution that he inspired, and some of the reasons (understandable if indefensible) for persisting public unease.

Pre-Darwinian concepts of evolutionâa widely discussed, if unorthodox, view of life in early-nineteenth-century biologyâgenerally went by such names as “transformation,” “transmutation,” or “the development hypothesis.” In choosing a label for his very different account of genealogical change, Darwin would never have considered “evolution” as a descriptor because this

vernacular English word implied a set of consequences contrary to the most distinctive features of his own revolutionary mechanism of changeâthe hypothesis of natural selection.

“Evolution,” from the Latin

evolvere

, literally means “to unroll”âand clearly implies an unfolding in time of a predictable or prepackaged sequence in an inherently progressive, or at least directional, manner. (The “fiddlehead” of a fern unrolls and expands to bring forth the adult plantâa true “evolution” of preformed parts.) The

Oxford English Dictionary

traces the word to seven-teenth-century English poetry, where the key meaning of sequential exposure of prepackaged potential inspired the first recorded usages in our language. For example, Henry More (1614â1687), the British poet and philosopher responsible for most seventeenth-century citations in the

OED

, stated in 1664: “I have not yet evolved all the intangling superstitions that may be wrapt up.”

The few pre-Darwinian English citations of genealogical change as “evolution” all employ the word as a synonym for predictable progress. For example, in describing Lamarck's theory for British readers (in the second volume of his

Principles of Geology

in 1832), Charles Lyell generally uses the neutral term “transmutation”âexcept in one passage, when he wishes to highlight a claim for progress: “The testacea [shelled invertebrates] of the ocean existed first, until some of them by gradual evolution were improved into those inhabiting the land.”

Although the word

evolution

does not appear in the first edition of the

Origin of Species

, Darwin does use the verbal form “evolved”âclearly in the vernacular sense and in an especially prominent spot: as the very last word of the book! Most students have failed to appreciate the incisive and intended “gotcha” of these closing lines, which have generally been read as a poetic reverie, a harmless linguistic flourish essentially devoid of content, however rich in imagery. In fact, the canny Darwin used this maximally effective location to make a telling point about the absolute glory and comparative importance of natural history as a calling.

We usually regard planetary physics as the paragon of rigorous science, while dismissing natural history as a lightweight exercise in dull, descriptive cataloging that any person with sufficient patience might accomplish. But Darwin, in his closing passage, identified the primary phenomenon of planetary physics as a dull and simple cycling to nowhere, in sharp contrast with life's history, depicted as a dynamic and upwardly growing tree. The earth revolves in uninteresting sameness, but life

evolves

by unfolding its potential for ever-expanding diversity along admittedly unpredictable, but wonderfully various, branchings. Thus Darwin ends his great book:

Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

But Darwin could not have described the

process

regulated by his mechanism of natural selection as “evolution” in the vernacular meaning then conveyed by this word. For the mechanism of natural selection only yields increasing adaptation to changing local environments, not predictable “progress” in the usual sense of cosmic or general “betterment” expressed in favored Western themes of growing complexity or augmented mentality. In Darwin's causal world, an anatomically degenerate parasite, reduced to a formless clump of feeding and reproductive cells within the body of a host, may be just as well adapted to its surroundings, and just as well endowed with prospects for evolutionary persistence, as the most intricate creature, exquisitely adapted in all parts to a complex and dangerous external environment. Moreover, since natural selection can only adapt organisms to

local

circumstances, and since local circumstances change in an effectively random manner through geological time, the pathways of adaptive evolution cannot be predicted.

Thus, on these two fundamental groundsâabsence of inherent directionality and lack of predictabilityâthe process regulated by natural selection could scarcely have suggested, to Darwin, the label of “evolution,” an ordinary English word for sequences of predictable and directional unfolding. We must then, and obviously, ask how “evolution” achieved its coup in becoming the name for Darwin's processâa takeover so complete that the word has now almost (but not quite, as we shall soon see) lost its original English meaning of unfolding, and has transmuted (or should we say “evolved”) into an effective synonym for biological change through time?

This interesting shift, despite Darwin's own reticence, occurred primarily because a great majority of his contemporaries, while granting the overwhelming evidence for evolution's factuality, could not accept Darwin's radical views about the causes and patterns of biological change. Most important, they could not bear to surrender the comforting and traditional view that human consciousness must represent a predictable (if not a divinely intended) summit of biological existence. If scientific discoveries enjoined an evolutionary reading of human superiority, then one must bow to the evidence. But Darwin's contemporaries (and many people today as well) would not surrender their traditional view of human domination, and therefore could only conceptualize genealogical transmutation as a process defined by predictable progress toward a human acmeâin short, as a process well described by the term “evolution” in its vernacular meaning of unfolding an inherent potential.

Herbert Spencer's progressivist view of natural change probably exerted most influence in establishing “evolution” as the general name for Darwin's processâfor Spencer held a dominating status as Victorian pundit and grand panjandrum of nearly everything conceptual. In any case, Darwin had too many other fish to fry, and didn't choose to fight a battle about words rather than things. He felt confident that his views would eventually prevail, even over the contrary etymology of word imposed upon his process by popular will. (He knew, after all, that meanings of words can transmute within new climates of immediate utility, just as species transform under new local environments of life and ecology!) Darwin never used the “E” word extensively in his writings, but he did capitulate to a developing consensus by referring to his process as “evolution” for the first time in

The Descent of Man

, published in 1871. (Still, Darwin never cited “evolution” in the title of any bookâand he chose, in labeling his major work on our species, to emphasize our genealogical “descent,” not our “ascent” to higher levels of consciousness.)

When I was a young boy, growing up on the streets of New York City, the Museum of Natural History became my second home and inspiration. I loved

two exhibits most of allâthe

Tyrannosaurus

skeleton on the fourth floor and the star show at the adjacent Hayden Planetarium. I juggled these two passions for many years, and eventually became a paleontologist. (Carl Sagan, my near contemporary from the neighboring neverland of BrooklynâI grew up in Queensâweighed the same two interests in the same building, but opted for astronomy as a calling. I have always suspected a basic biological determinism behind our opposite choices. Carl was tall and looked up toward the heavens; I am shorter than average and tend to look down at the ground.)

My essays generally follow the strategy of selecting odd little tidbits as illustrations of general themes. I wrote this piece to celebrate the reopening of the Hayden Planetarium in 2000, and I followed my passion for apparent trivia with large tentacles of implication by marking this great occasion with a disquisition on something so arcane and seemingly irrelevant as the odyssey of the term “evolution” in my two old loves of biology and astronomy. In fact, I chose to write about “evolution” in the biological domain that I know in order to explicate a strikingly different meaning of “evolution” in the profession that I put aside, but still love avocationally. I believe that such a discussion of the contrast between biological and cosmological “evolution” might highlight an important general point about alternative worldviews, and also serve as a reminder that many supposed debates in science arise from confusion engendered by differing uses of words, and not from deep conceptual muddles about the nature of things.