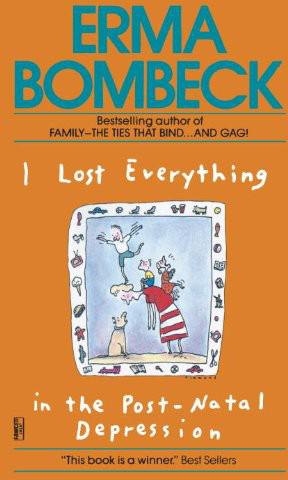

I Lost Everything in the Post-Natal Depression

Read I Lost Everything in the Post-Natal Depression Online

Authors: Erma Bombeck

The other day I went into the Bureau of Motor Vehicles to have my driver’s license renewed.

The man behind the counter mechanically asked me my name, address, phone number and, finally, occupation.

“I am a housewife,” I said.

He paused, his pencil lingering over the blank, looked at me intently, and said, “Is that what you want on your license, lady?”

“Would you believe, Love Goddess?” I asked

dryly.

In my lifetime, I have had many identities.

I have been referred to as the “Tuesday pick-up with the hole in the muffler,” the “10:30

A.M.

standing in the beauty shop who wears Girl Scouts anklets,” and “the woman who used to work in the same building with the sister-in-law of Jonathan Winters.”

Who am I?

I’m the wife of the husband no one wants to swap with.

Also by Erma Bombeck:

AT WIT’S END

*

“JUST WAIT TILL YOU HAVE CHILDREN OF YOUR OWN!” (with Bil Keane)

*

IF LIFE IS A BOWL OF CHERRIES—WHAT AM I DOING IN THE PITS?

*

AUNT ERMA’S COPE BOOK: How to Get From Monday to Friday … in 12 Days

*

MOTHERHOOD: The Second Oldest Profession

FAMILY: The Ties That Bind … and Gag!

*

I WANT TO GROW UP, I WANT TO GROW HAIR, I WANT TO GO TO BOISE

*

Published by Fawcett Books

A Fawcett Crest Book

Published by Ballantine Books

Copyright © 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973 by Field Enterprises, Inc.

Copyright © 1970, 1971, 1972 by The Hearst Corporation

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Alternate Selection of the Doubleday Book Club

eISBN: 978-0-307-77825-3

This edition published by arrangement with Doubleday & Company, Inc.

v3.1

To BILL, who said,

“Whatya been doin’ all day?”

Before you read this book, there are a few things you should know about me.

I consider ironed sheets a health hazard.

Children should be judged on what they are—a punishment for an early marriage.

There is no virtue in waxing your driveway.

Husbands are married for better or worse—but not for lunch.

Renaissance women were beautiful and never heard of Weight Watchers.

Mothers-in-law who wear a black armband to the wedding are expendable.

Missing a nap gives you bad skin.

Men who have a thirty-six-televised-football-games-a-week-habit should be declared legally dead and their estates probated.

For years, I have worked at being a simple, average housewife. I am ready to face the facts. I’m a loser. Excitement

for me is taking a Barbie bra out of the sweeper bag. Fulfillment is realizing I am the only one in the house who can replace the toilet-tissue spindle. Adventure is seeing Tom Jones perform and throwing my hotel key at his feet (only to discover it’s the key to my freezer).

Would it shock you to know that as an average housewife I have never been invited to an aspirin lecture? You know the commercial I’m talking about. There’s this ratio-balanced roomful of people sitting around finding out everything they’ve always wanted to know about aspirin but were afraid to ask.

“Can I drive a car after taking aspirin? Can I take aspirin with other medication? What are the ingredients of aspirin?” I worry about me. I don’t want to know anything about aspirin.

After twenty-three years of marriage, you would have thought that once during that time some stranger would have called and asked me what laxative I use. My kids never tell me what the dentist said. My husband never smells his shirts and smiles. We rarely spend an evening sitting around reading the ingredients on dog-food cans. And I can’t tell you when was the last time my husband offered to shampoo my hair.

I was telling my neighbor, Mayva, how commercials had evaded me and she said, “You ninny, let me see your handbag.”

I opened it to reveal the usual collection of women’s junk.

“That’s your problem,” she said. “You’ll never get into a commercial traveling like that.” She opened her purse. In it was a large bottle of Milk of Magnesia (“You never know when you are going to sit on a park bench with someone who needs a coating on their stomach.”), a package of breath mints, a pound of Mountain Grown coffee, a hair spray, a bottle of dishwashing detergent, a

compound to soak your dentures, a can of floor wax, a room deodorizer, and two rolls of (whisper) toilet paper.

“If you want to be a normal, average housewife,” she said, “you’ve got to be ready for ’em.”

Yesterday, I knocked on Mayva’s door. “Guess what?” I said. “It worked. I almost got in a commercial. I was in the supermarket and I was approached by this man who wanted to know what laundry soap I used. I opened my handbag and showed him this big box. He was pleased as punch. He said, ‘What would you say if I told you I’d give you

two

boxes of an inferior brand for this one?’ I told him I’d say,

‘You’re on, Barney!’

”

“You blew it,” said Mayva softly.

“I’m afraid you’re right,” I said.

I suppose I should be depressed, but I have a theory there are some things in this life you cannot control. It’s psychological defeat. No matter what you do you cannot win.

Take my son. The other day I dropped him off at the tennis court and as his opponent walked over to introduce himself, my son froze. After the boy left, he slumped to the bench, holding his head between his knees. “Did you see him, Mom?” he asked miserably.

“He was wearing a sweat band.”

I could have cried for him. Any fool knows sweat bands always finish first. I wanted to comfort him, but in my heart, I knew the outcome. He was psychologically defeated.

I know. I was defeated for the title of Miss Eighth Grade Perfect Posture when I saw Angie Sensuous was a finalist. Angie was never carried in a fetal position. She was born sitting upright.

I knew I had blown the presidency of the Forensic League when I walked out on the stage dragging a piece of toilet tissue on my left shoe. I knew I could never shape

up when I walked into the YWCA exercise class dressed in faded pedal pushers and knee-length Supp-hose when the rest of the class had leotards.

Don’t ask me how you know. You just do. Your dog will never get well when you take him to the vet and all the other dogs have rhinestone collars and leashes and yours has a fifty-foot pink plastic clothesline around his neck.

You know your day is lost when you go into town and the elevator operator takes you straight to the basement budget store without asking.

You know instinctively that you will never get a hundred-dollar check cashed when the button falls off your coat. I always loved Fannie Flagg’s remark that she could have won the Miss America pageant, but she got the wicker chair in the bathing suit competition. She knew.

I try, but somehow I am always the woman in the wrong line. Lines are like a foreign language. You have to know how to read and to translate them. What looks to me like a thirty-second transaction invariably ends up as a tenor thirty-minute wait.

I am always behind the shopper at the grocery store who has stitched her coupons in the lining of her coat and wants to talk about a “strong” chicken she bought two weeks ago. The register tape also runs out just before her sub-total.

In the public rest-room, I always stand behind the teen-ager who is changing into her band uniform for a parade and doesn’t emerge until she has combed the tassels on her boots, shaved her legs, and recovered her contact lens from the commode.

In the confessional, there is only one person ahead of me. A priest. Now who could be safer following a priest into the confessional? Anyone but me. My priest has just witnessed a murder, has not made his Easter duty since 1967, and wants to talk about his mixed marriage.

At my bank the other day I cruised up and down a full five minutes trying to assess the customers. There was the harried secretary with a handful of deposit slips. I’d be a fool to get behind her. At the other window was a small businessman with a canvas bag of change. I figured he had probably drained a wishing well somewhere and brought three years of pennies in to be wrapped. In the next line was an elderly gent who seemed familiar with everyone. He was obviously going to visit his money and his safety deposit box.

I slipped in behind a little tyke with no socks, dirty gym shoes, and a Smile sweatshirt. He had to be a thirty-second transaction.

The kid had not made a deposit since the first grade. He had lost his passbook. His records were not in the bank’s regular accounts but were in the school section. He did not know his passbook number or his homeroom teacher’s name, as she had been married near the beginning of the school year. Each of 2,017 cards of the school’s enrollment had to be flipped. He deposited twenty-five cents.

He hesitated as he looked at his book, noting he had made fifteen cents in interest. He wished to withdraw it. As he was only old enough to print, he needed his mother’s permission. His mother was called on the phone, which took some time, as she was drinking coffee at a neighbor’s home. She said no.

He then wanted to know if he could see where they kept his money and if he could have one of the free rain bonnets they advertised. He asked directions to a drinking fountain and left—twenty-three minutes later.

I am psychologically defeated when I try to take one of those tests in a magazine to find out if I am a fit housewife and mother and I can’t find a pencil in a six-room house. And when I do finally tally up my score, I discover I am not suited for marriage and motherhood,

but have the aptitude and attitude for being a nun who drops out of the convent to sing and tap dance and make hit records.

Sometimes I don’t know what’s the matter with me. I find myself sitting around admiring weak kings. I don’t seem to have the confidence that working women do. For example, the idea of taking a simple test to renew my driver’s license was enough to make me drink my breakfast out of an Old Fashioned glass for a week.

I was standing in this long line at the Department of Motor Vehicles recently when I noticed the woman in front of me. She seemed just as frightened as I was. Her face was ashen, her eyes fixed, there was no pulse, and she dragged her feet like bowling balls.

I turned to the woman behind me. Either she was (a) wearing petite pantyhose that were crushing her kidneys or (b) she had just got word that her visiting mother-in-law had broken her hip and couldn’t be moved for three months.

Me? I was terrified and suspicious of the whole outfit. In fact, I regard the test as a concentrated effort on the part of the Department of Motor Vehicles to get me off the road. I have taken enough tests in my time to look for the hidden words like “always” and “everybody” and “never.”