If Britain Had Fallen (37 page)

36

Anti-invasion defences under construction at Anne Port, Jersey. (In the background is a Martello tower, built during the Napoleonic wars)

37

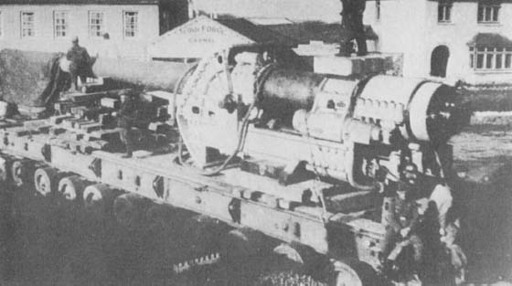

A captured French gun being towed into position on Guernsey for use against British shipping

38 and 39

A gas-driven van and a horse-drawn van on Jersey

40

Residents of Jersey collecting Red Cross food parcels

41

The Germans burying the washed-up bodies of British servicemen with full military honours

42

The New Jetty, Guernsey, awaiting demolition in case of an allied invasion. (The bombs were never in fact detonated)

43

Parliament Square, July 1940

Most people reacted remarkably calmly to the news of impending deportation, partly because rumours about it had been circulating for some time. One Jerseyman, then aged twenty, who had fallen foul of the occupying forces a few weeks earlier, was not surprised, he remembers, when ‘I went home one particular day for my lunch and my mother handed me an envelope and it was my sealed orders as to what to do to prepare myself for the Fatherland’. As a single man he was philosophical about the coming ordeal. ‘I thought, “Well, if I do go to Germany I couldn’t be any worse off than under German rule on the island. They could do what they liked with me” in either place.’ Another man and his wife endured a week of waiting after reading the notice of the impending deportations in the local newspaper, and were then ordered one afternoon to report the following morning. She still vividly remembers the moment when the blow actually fell:

My husband was out, and a parish official came with a German, and he handed me a bit of blue paper. He said ‘This is your instructions, will you please read it? And sign it?’ And then my husband came in and … he was very cross and he read this notice and said, ‘I’m not going to sign this. I don’t wish to take my wife and family to Germany. So our official, poor old man, he was rather old, he said, ‘Come, come, Mr Stevens, do be reasonable, don’t upset things.’ So my husband got even crosser, he said, ‘No, I will not sign this. I’m not going to Germany. I don’t intend to go to Germany’, and looked at the German and said, ‘I’m not going to sign your paper. You can shoot me, if you like.’ There was a tense moment, then this German said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m not allowed to shoot you.’ So I thought ‘To hell with all this’, and I signed the form to get rid of them.

The instructions the Stevens had been given were to take all the clothes and bedding they could carry for themselves and their two children, then aged two and six, with food and drink sufficient for forty-eight hours. Of their actual departure Mrs Stevens remembers, ‘It was quite an incredible feeling. You’ve got a whole house, you’ve got your belongings and you’re walking out of your house, on a hot September day, with literally all the clothes you can get on your back and round your neck, and that’s all—as far as you know, that you’ve got in the world.’ Her fears for her children, she remembers, were tempered with ‘regret they weren’t older because, not only did we have to carry ourselves and our clothes and our blankets, but we had

to

carry the children and the children’s belongings, which made it a really terrific load’. Light relief, of a kind, came a few minutes later when they reached the bus provided to carry them to the assembly point and found on it a family from ‘down the road, with a small boy, and he was really being extremely fractious and his mother turned round to him and said, “Gerald, if you don’t be quiet, I won’t take you to Germany with me.” ‘

One Jersey man, then a boy of seven, remembers that his first reaction ‘was a sense of excitement’. A woman of the same age also does not ‘remember feeling scared or worried or anything’, though a friend later reminded her how she had ‘stood outside the sweet shop’, stamped her feet and said ‘I’m not going’. Her chief memories of a day that must have been one of appalling anxiety for her parents were not disagreeable, but of sleeping on the deck of a boat with a life-jacket on, and carrying her doll wrapped up in a blanket.

All told, about four per cent of the wartime population of the Channel Islands were deported, representing a cross-section of both sexes and all ages, compared with the twenty-five per cent of the population, drawn exclusively from the younger adult males, whom the Germans talked of removing from the British Isles. How did the vast majority, who were not personally affected, react to this blow to their neighbours? Most, despite the obvious temptation to look the other way for fear of offending the Germans, behaved, at least before the boats left, with a humanity that did them credit. In the weekend before the first ships left Guernsey—they were supposed to go on Monday 21 September, but did not in fact sail until Thursday 24—the other residents, despite their own shortages and the prevailing rationing, provided gifts of clothes, shoes—who knew how far the deportees might have to walk?—and food while a young local caterer, on the list himself, organised the collection of food and provided a supply of soup, sandwiches and hot drinks. On Jersey the departure of the deportees, some of them wearing small Union Jacks in their hatbands, was made the occasion of a mass demonstration of sympathy from the other islanders, who lined the streets leading to the harbour, setting up shouts of ‘Churchill!’ and ‘England!’, and eventually fourteen youths, who were playing football with a German helmet, were arrested.

Curiously enough, however, no sooner had the boats left or, in some cases, even before they had left, than the looters moved in. The couple who had climbed on the bus with the fractious small boy, for example, were sent home late that night to await another boat, and, the husband remembers, ‘We came back and found the house fairly well emptied of anything valuable like spare food, spare clothing, quite a lot of wine I had and the obvious valuables. It wasn’t wanton looting but people who had perhaps no luxuries heard or saw that we were going and came in and said to the girl we’d left in charge to clear up the house, “Mr Stevens has some wines, Mr Stevens has some tea, he said if he ever went away we could have it.” And it went.’ Others who returned home in similar circumstances had equal shocks. One family was forced to borrow coal to keep warm for the few days of liberty left to them. Another, arriving home in

the dark, found that even the electric light bulbs had vanished since that morning. One child, whose father had, from humble beginnings, built up his own garage business, was moved to tears at his father’s distress at finding ‘everything missing, windows broken and stuff [gone] that my father treasured for years’. ‘If it had been the Germans who had taken it’, one woman feels, ‘well, you could have accepted it, but to know that it was your own friends that had stripped the place, it was terrible.’ Often bombed-out families in England, finding possessions which had survived the blitz looted, suffered a similar sense of outrage, though they were spared the experience many families deported to Germany suffered three years later when they came back to discover their furniture gone and sometimes even the roofs stripped from their houses and the floor-boards taken up, a silent monument to the shortage of fuel.