If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late (20 page)

“Can I see it?” Yo-Yoji took the ball from Cass and turned it around in his hand.

“Careful,” said Max-Ernest. “It’s very old and very valuable.”

“Hey, look —” Yo-Yoji succeeded in loosening the band. It spun around —

“I told you — now you broke it!”

“Dude, first of all, why are you hating on me all the time?”

“Wha-what do you mean?” Max-Ernest sputtered. “I’m not —”

“Yeah, sure you aren’t! Second of all, I’m pretty sure it’s supposed to spin like this.”

“What? Like a combination lock or something? Let me see,” said Max-Ernest, obviously very skeptical. He reached for the Sound Prism.

“No, let

me,

” said Cass, reaching at the same time.

As they collided, the Sound Prism dropped out of Yo-Yoji’s hand. It fell onto a bump in the middle of the tent — and it split evenly in two.

“It hit the rock!” Yo-Yoji picked up a half in each hand, peering inside one after the other. “Well, the good news is we got it open. There wasn’t a trick — it was just stuck.”

“What’s the bad news?” asked Cass.

“Look — there’s no name inside, just a poem.”

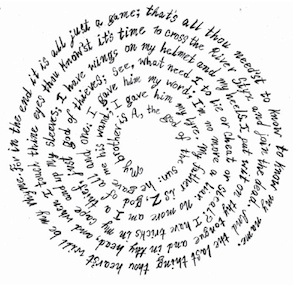

Engraved in the alabaster, the poem spiraled around the inside of one half of the Sound Prism. The tiny letters looked like the inscription on the inside of a ring.

“Here, you read it,” Yo-Yoji said, handing the two halves to Cass. “I’m kind of dyslexic.”

Max-Ernest looked at Yo-Yoji, as if about to say something.

But then Cass started to read aloud:

“Aaargh, it’s so annoying — we don’t have time for this!” said Cass, putting down the two halves of the Sound Prism. “What does it mean? What’s the name?”

Yo-Yoji shook his head. “I’m not really good with this kind of poem — the kind I write don’t rhyme. Plus, it’s, like, in Shakespearean.”

“I think it’s kind of like a riddle — you can tell by the way it ends,” said Max-Ernest. “Can I see it? I mean, if I’m allowed.”

“Ha-ha.” Cass rolled her eyes and handed him the two halves of the Sound Prism.

Max-Ernst looked inside —

“Well, the river Styx is from Greek mythology, right? It’s the river on the way to Hades. . . .”

“Yeah, maybe . . . I mean, OK,” said Cass.

“Think about it — that means if it was a secret code, Greek mythology would be the key. So

A

is Apollo and

Z

is Zeus . . .”

“Nice!” said Yo-Yoji, looking at Max-Ernest with new respect. “You’re pretty good at that stuff, huh, bro?”

“I guess. Hey, Yo-Yoji . . .” Max-Ernest hesitated. “Well, one of my doctors thought I was dyslexic, so I know lots of exercises you’re supposed to do. I could show you. If you want.”

“I don’t usually like exercises very much, but, um, sure, if you think they’re good. . . .” Yo-Yoji wasn’t all that much better at emotions than Max-Ernest, but he had an idea what Max-Ernest was trying to say.

Cass smiled to herself. She knew better than to ruin the moment by saying anything.

Cass’s grandfathers didn’t seem at all surprised by the kids’ sudden interest in fly-fishing, or in their even more sudden interest in Greek mythology. Grandpa Larry loved mythology as much or more than Grandpa Wayne loved fishing, and he considered it perfectly natural that his granddaughter would ask him who the Greek god of thieves was.

“Ah, well, there’s a story that goes along with that,” Larry said as Wayne cast out over the lake with his makeshift fishing rod. “You see, before he was really the god of anything, and he was just a mischievous little boy god, he stole a herd of cows from his big brother, Apollo. Apollo went ballistic and in order to appease Apollo, Zeus made him return the herd. Problem was — two cows were missing. Their hides had been turned into strings and strung over a tortoiseshell, making the first lyre. Luckily, Apollo loved music so much that he forgave his little brother, and even gave him his magic wand in return for the lyre. And that’s how this little boy became not only the god of thieves, but the god of magic as well.”

“That’s a great story,” said Cass impatiently, “but what was the god’s name?”

Finding

the homunculus’s trail wasn’t very difficult; they identified it by all the bones and scraps and candy wrappers that the homunculus had left in his wake.

Following

the trail was another matter. In order to avoid all the low-hanging branches, they had to crawl most of the way.

“Ouch! These scratches aren’t good for my eczema,” Max-Ernest complained as he pushed branches out of his face. “And I know my allergies are going to get really bad —”

“Forget your allergies,” said Cass. “If we don’t have the name right, we’re going to have a lot worse problems.”

They knew they were getting there when the bones on the ground started appearing closer together: mostly little leg and thigh bones but there was the occasional whole carcass (bird? squirrel?!) and two or three bones from larger animals that the kids preferred not to identify.

Finally, about a quarter mile from their campsite, they reached a clearing in the woods. Here the bones were so dense they created a carpet. It was a gruesome but — with the dappled sunlight and canopy of trees above — a not unbeautiful sight.

On the other side of the clearing, surrounded by a circle of rocks, a campfire blazed. A pillar of smoke curled upward. The smell of grilling meat filled the air.

“Look at that,” said Max-Ernest. “What if the ranger sees?!”

“Forget the ranger — what if there’s a forest fire?” said Cass.

“I dunno, smells pretty excellent to me,” said Yo-Yoji.

Behind the fire stood a tall fir tree with a burned-out base; they all jumped, startled, when the homunculus stepped out of it.

“It better smell good — I’ve been cooking all morning. And don’t worry about the ranger — I know his schedule. He’s on the other side of the mountain right now.”

Cass decided not to lecture him about fire safety.

Instead, she took a brave step toward the homunculus and asked, “So, um, Mr. Cabbage Face, was the Jester’s name

Hermes

?”

“Shhh!”

“But you said . . .”

“Sure, sure, but names have power. In case you didn’t notice, mine made me rise from a grave.”

“Sorry, I didn’t think about that,” said Cass, pale.

“So do you want your three wishes, Cassandra?”

“I get three wishes . . . ?”

“Of course not! Why does everybody always think I’m some kind of genie?” The homunculus made a loud hacking sound that might have been a laugh. His brown, broken teeth made his mouth look like a jack-o’-lantern.

“You know, I would have found you eventually — if you’d just called me a few more times,” said the homunculus, studying Cass. “Pretty resourceful, tracking me here in the mountains.”

“She’s a survivalist,” said Max-Ernest proudly.

Cass looked down, suddenly embarrassed.

“Ah, well, that explains it! Come now, we can talk business later. Let’s eat.”

The homunculus made them all sit around the fire. Nearby, he’d laid out piles and piles of food on a bed of pine needles.

“Hey, that’s our food — you stole it!” said Max-Ernest, recognizing the Camembert.

“Don’t get your knickers in a twist — it’s not all yours. Some of it’s from other campsites. Besides,” continued the homunculus blithely, “that Camembert needs at least a week before it’s going to be ripe. And this Zinfandel has no nose at all. How can you drink such mediocre wine? Now, if you like, I have a wonderful Châteauneuf-du-Pape courtesy of some hikers from Montreal.” He held up a fancy bottle of wine. “Those fellows had taste!”

Yo-Yoji stopped him before he could start pouring. “Um, do you have anything else? We don’t really like wine.”

The homunculus looked appalled. “You don’t drink wine?! Don’t tell me you’re beer drinkers! I didn’t take you for such ruffians.”

They shook their heads.

“We don’t drink beer, either,” said Max-Ernest.

“Ah, so then it’s liquor for you,” said the homunculus, relieved. “I agree, quite right — why monkey around with the soft stuff? So what can I get you — vodka? Gin? I have a very nice single malt scotch.”

They shook their heads.

“Tequila with a squeeze of lime? Not the classiest, true, but what the heck — we’re camping, right?”

They shook their heads.

“A drop of cognac?”

They shook their heads.

“Why are you insulting my hospitality like this?” The homunculus looked at them, distressed.

“We’re

kids.

We drink soda and stuff,” said Max-Ernest.

“You know what’s in soda? Sugar and food coloring. And diet soda? Worse. I refuse to let you destroy your bodies with soda!” The homunculus drew himself up in a huff.

Cass was about to point out that it was little hypo-critical for him to forbid soda when, judging by all the wrappers they’d seen, he ate plenty of candy, but then she thought better of it.

They compromised with lake water (purified with tablets Cass had in her backpack). And then they proceeded to feast on all the stolen goods. Or rather, the homunculus did. The others didn’t have much of an appetite.

All they could do was stare at the long gray hairs that sprouted from his nose and his ears — and try to avoid smelling his breath.

“I’m sorry there’s so little,” said the homunculus, his mouth full of cheese.

He held a charred sausage in one hand and a barbecued drumstick in the other. He might have looked like a munchkin, but he ate like a T. rex. “I have to make do with what’s around. My life isn’t what it used to be. Gone are the days of dining with King Henry the Eighth. . . .”

“You ate with Henry the Eighth?” asked Max- Ernest.

“In a manner of speaking. I ate with his hogs.”

“So that story we read was true? About you escaping from the hogs with the Jester?” Cass asked eagerly.

“Well, I don’t know what you read — I’m sure people write all kinds of things about me. That happens when you’re a celebrity. But yes —”

The kids watched in fascination as he sucked the marrow out of a chicken bone with lightning speed, then tossed the bone onto a pile behind him.

“And the Jester — was he really a jester?” asked Cass.

“Of course — why wouldn’t he be? Not the funniest maybe — although he thought he was. You know what they say about not laughing at your own jokes? Well, he never learned it.”

“I knew it,” said Cass. “And what about Lord Pharaoh?”

The homunculus scowled. “What about him?”

“Well, the story said that you . . . met each other years after you ran away. What happened?”

“I ate him,” said the homunculus, biting into his sausage.

The kids couldn’t hide their looks of horror.

He smiled, sausage juice running down his chin. “Oh, don’t worry — I cooked him first. I’m not a barbarian. Sadly for me, he was not a young man anymore, so he wasn’t very tender. But even old flesh isn’t bad, if you know how to prepare it properly. The key is to brown the meat first to seal in the juices.”

The kids all shifted nervously on their pine-needle seats.

“What’s the big deal? Meat is meat! You know what they say — tastes like chicken, right? Although, honestly, more like pork . . .”

“I don’t care how it tastes, I couldn’t ever eat a person.” Cass shoved her pile of food away as if it were the person in question.

“I thought you were a survivalist! You’ll never last in the wild if you’re so squeamish,” said the homunculus. “Personally, I would consider it an honor to be eaten — assuming I was already dead, of course.”

“

Can

you die?” asked Yo-Yoji.

The homunculus eyed him suspiciously. “Why do you want to know?”

“Uh, no reason,” said Yo-Yoji quickly. “Except these guys said you were five hundred years old —”

“You forgot to say, and looking pretty good on it!”

Cass pulled the Sound Prism out of her sweatshirt pocket. “So, Mr. Cabbage Face, am I supposed to give this to you? It’s sort of yours, I guess.”

“No, it’s yours. But please — would you play the song? It’s been a while since I heard it up close. Matter of fact, no one’s called me on the Sound Prism for a couple hundred years. Last one was a boy named Gilbert. Excuse me,

Sir

Gilbert. What a spoiled brat!”

Cass obligingly tossed the ball into the air. It played the same song it always played — but it was different with Cabbage Face himself there.

Listening, the homunculus looked at the ground, lost in time.

Was that a tear in his eye? It was hard to be sure.

She had to ask: “So, then, am I the . . . rightful heir?”

“Of course you are,” said the homunculus. “I could tell the Sound Prism was yours the second I laid eyes on you.”

“You could? How?” asked Cass in amazement.

“Those pointy ears of yours. Just like the Jester’s. Anybody could see from a mile away . . .”

Cass felt her ears reddening at the homunculus’s words. “The Jester? I’m descended from the Jester?”

She couldn’t believe it: somebody else had walked the earth with her big, pointy, target-of-joke-y ears.

She tried to remember everything she’d read about the Jester and the way he’d saved the homunculus from his horrible master. He may have been named after the god of thieves, but the Jester — Hermes — was a hero, and somehow, in some way, he was hers.