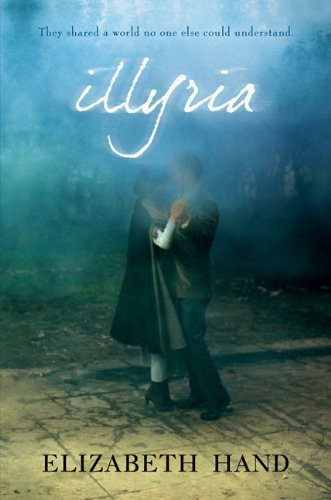

Illyria

Authors: Elizabeth Hand

Tags: #Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 10-12), #Children's Books - Young Adult Fiction, #Love & Romance, #Social Issues, #Social Issues - Adolescence, #Adolescence, #Cousins, #Performing Arts, #Interpersonal Relations, #Theater, #Incest, #Performing Arts - Theater

Illyria

Elizabeth Hand

For Russell Dunn, who made it real, then and now

ROGAN AND I WERE COUSINS; OUR FATHERS

were identical twins. Rogan was the youngest of six boys, I the youngest of six girls. Growing up, there were always jokes about this symmetry, even though everyone in the Tierney clan bred prolifically--there were twenty-six first cousins, divided among five families.

Still, only Rogan and I were ever called kissing cousins, despite the fact that our older brothers and sisters were also paired off, age-wise, as neatly as if our parents had timed their conjugal relations so that their children would all be born within a few days of each other, and Rogan and I actually on the same day. I arrived in the early morning, Rogan moments before midnight. Later, when we were adolescents, the facts of our birth (we always thought of it as

our

birth) conveniently fulfilled our need to find meaning in everything about ourselves.

So Rogan was darkness, I was light, and over the years the metaphor was extended to include just about every doomy literary reference you can imagine--Caliban and Ariel, Peter Pan and Wendy, Heathcliff and Cathy, Abelard and Heloise, Tristan and Iseult, Evnissyen and Nissyen ...

You get the idea.

2

Ours had been a noted theatrical clan, a line of performers stretching back to Shakespeare's day. Our great-grandmother was the once-famous actress Madeline Armin Tierney. I was her namesake. Yeats was rumored to have written his poem "The Last Stone of Carrowkeel" for Madeline, and our aunt Kate claimed that the character of Caitilin Ni Murrachu in James Stephens's

The Crock of Gold

was inspired by her, as well.

But the family forsook the stage. Madeline gave up acting when she married. Her children and grandchildren regarded the theater with a mixture of bemusement and condescension, fear and guilt, the same emotions stirred by the even rarer mention of sex.

Only Aunt Kate dwelled on this abandonment with grim persistence.

"Like cutting down a tree in its prime," she'd tell Rogan and me, the only two who ever listened. "Nothing good ever comes of that. Never ever ever."

There were remnants of family history scattered throughout our homes at Arden Terrace. Framed billets advertising performances by Edwin Booth or Otis Skinner or Charlotte Cushman, with various Tierneys in supporting roles. Peter Pangloss in

The Heir at Law,

Madame Trentoni in

Captain Jinks;

the Fool, Hermione, Dogberry. A lurid painting of a nameless ancestor as one of the witches in

Macbeth.

Mother-of-pearl opera glasses, silver spoons engraved with obscure jokes: "To His Highness from a Rogue."

We retained theatrical superstitions, as well, unmoored from their element and thus meaningless. Peacock feathers were banned from all our homes. It was considered lucky for a cat to sleep on one

3

of our parochial school uniforms. In the carriage house where Madeline once stored her tattered scripts, and where Aunt Kate now lived, a ghost light burned in an upper window, a forty-watt bulb in a floor lamp without a shade. Our attics were full of ruined costumes, tattered moth's-wings of burned velvet and lace that had been court gowns; crinolines reduced to hoops of whalebone; black satin disks that, when smacked upon a cousin's unsuspecting head, burgeoned into top hats; lady's gloves that still smelled like the ladies who had last worn them; sinister puppets and jointed dolls used as models for the wardrobe mistress; old photos of Fairhaven, the island in Maine where Madeline had kept a summer home.

But most of the photographs of Madeline had ended up in Aunt Kate's house. Faded silver-print and sepia images, water damaged or foxed with mold. Still, you could see how striking she'd been, with large, very pale eyes that looked ghostly in black-and-white, a high forehead and thick dark hair, melancholy mouth, and the faintest constellation of freckles across her apple cheeks. She was piquant rather than pretty; yet there was also something unsettling in her looks, though maybe that was just the old-fashioned photography. All the pictures seemed slightly out of focus.

And I could never imagine her eyes having a color. Were they blue? Gray? Green?

They looked like ice. I couldn't imagine her ever crying.

Fey,

said Aunt Kate whenever she mentioned her. A word I didn't understand, especially when she added, "You look like her, Maddy."

Because I was ugly. Really ugly; everyone thought so. Crooked buckteeth and glasses, upturned nose, bad skin. The grown-ups called

4

me Skinny Wretch--fondly, but still. Only Aunt Kate would look at me and shake her head, sitting at her dressing table surrounded by her beautiful clothes, Pucci dresses, Betsey Johnson shifts, Yves Saint Laurent blouses transparent as a screen door. On her right hand she wore a ring that had belonged to my great-grandmother, with an emerald roughly the shape and size of a cat's eye.

"You're beautiful, Maddy. Those legs? Just you wait. And when your braces come off? And the glasses?

Glamorous.

You're going to be so

glamorous--"

And she'd give me a special bar of soap from France, or astringent ointment from London that smelled like coal smoke. "Just you wait."

At my age, my great-grandmother was already beautiful. By the time she was sixteen, she was famous. As a girl, Madeline created unforgettable portrayals of Rosalind, Juliet, Titania, Perdita, and especially Viola, as well as less memorable turns in works like

Storming Castle Dora

and

The Blue-Footed Boy.

"Unforgettable." That was the word attached to Madeline throughout her career, in every torn clipping I ever read, every review of every performance, every stagy publicity photo that appeared as ancient and remote to me as a stone tablet. Madeline's Unforgettable Cleopatra. Her Unforgettable Viola. Her Unforgettable Series of Unforgettable Triumphs, Never to Be Forgotten.

Only, of course, it's all forgotten now. It was all forgotten then, since none of our parents had ever known Madeline as anything but a fractious old woman holed up in Fairview, her decaying Yonkers mansion. Even in her dotage she was too self-absorbed to pay much attention to her own five children, let alone her grandchildren.

5

But she'd made a good marriage to a wealthy developer named Rosco O'Meara, a man who anticipated the late-twentieth-century vogue for gated communities by nearly a century. They had five children, all of whom retained Madeline's maiden name. Almost unheard-of at the time, but Madeline belonged to a dynasty, and she was determined it would live on. Her twin brothers, also noted thespians, died of misadventure and left no children. She was the last of her line.

In the early 1900s, Rosco built Arden Terrace, a speculative venture consisting of a score of expansive Shingle-style and Tudor and Gothic homes, along with carriage houses, guesthouses, and various outbuildings, in a huge cul-de-sac overlooking the Hudson River. Artists flocked there from the city--North Yonkers was an exurb in those days, with fields and woodlands and bald eagles nesting along the river--and Arden Terrace became an enclave of successful writers and actors and editors, doctors and lawyers and a stockbroker.

Lovely and otherworldly as Arden Terrace was, it was also vulnerable. When the stock market crashed in 1929, no fewer than seven residents killed themselves, including Madeline's husband. Not, however, Madeline, who seemed to have absorbed the cumulative resilience and resourcefulness of all those plucky heroines she'd once played (her sole substantial flop was as Juliet) and who during the Depression bought up, one by one, all the houses surrounding her own. Her children ended up living in those homes, like hermit crabs scuttling into empty shells; and then

their

children, Madeline's grandchildren; and finally my own generation of kids.

By which time Arden Terrace resembled some mad architectural

6

folly spread out across one of the more desirable pieces of real estate in the city. Year after year, the Hudson River moved slowly, far below the turrets and balconies of our ersatz fortress; the tulip trees shed their yellow leaves; and snow covered the slate roofs of the carriage houses and guest cottages where the oldest Tierneys now lived. When summer came, the cul-de-sac was taken over by an occupying army of children in Keds and dungarees and striped shirts from John Wanamaker. Rock and roll blared from upstairs bedrooms, while a legion of mothers and aunts and grandmothers sat on Fairview's immense porch, talking and smoking and drinking whiskey sours as they watched the sun set over the Palisades.

Rogan's father and mine grew up in Fairview, along with their sisters. Later, Rogan's father inherited the mansion--he was the older twin by twelve minutes--and Rogan grew up there. My father moved into the house across the street, a less grand Queen Anne home that still had five bathrooms, exorbitant for the time, and six bedrooms.

That was where I grew up. Though the truth was, I spent as much time at Rogan's home as my own, and nearly as much time where our other cousins lived. During the day we all attended St. Brendan's School, several blocks away, up a winding hill shaded by old apartment buildings and elm trees, all now long gone. Every afternoon we raced home and changed from our uniforms into what were then called play clothes--a misnomer, since our after-school activities were more like the extended rehearsal for a street-theater production of

Lord of the Flies.

We moved from house to house to house like invading army ants. We devoured everything we could find, terrorized the

7

youngest children, raided toy chests and attics, crowded into basement recrooms to watch

Star Trek

and

Superman,

stole each other's record albums and baseball cards and Barbie clothes, gave too much food to goldfish and dogs that were not our own--all until we were driven back outside by irate adults.

Whereupon we'd move next door, or across the road, or down to the woods overlooking the river, and the whole cycle would begin again.

And Rogan?

There was never a time when I did not know Rogan.

We were the youngest in our generation of cousins. As the youngest girl, I wasn't coddled; mostly tolerated by my sisters and ignored by our parents.

But as the youngest boy, Rogan was bullied and beaten and tormented, relentlessly, cruelly; almost absently.

"Why?" I once demanded of Rogan's brother Michael. I'd jumped onto him from a first-floor balcony at my house when I saw him pounding Rogan on the lawn below. Michael grabbed me and tossed me onto the early-spring grass as though I were a burr that had stuck to him, and not a gangly fourteen-year-old girl with glasses. Rogan ran off, his face crimson with tears. I stumbled to my feet and shouted at Michael, "Why can't you just leave him alone?"

"What?" Michael looked at me, his blue eyes grave with astonishment. I might have asked him why we had to eat or drink or attend Mass on Sundays. "Because he'd be

spoiled."

Spoiled. It was the worst thing you could be. Only children were spoiled, not that we knew any. Aunt Kate, who'd never married and

8

who had kept her looks, along with a pied-à-terre in Greenwich Village--she was spoiled. Younger siblings by definition were spoiled, since in some obscure way they'd spoiled the paradise occupied by their older brothers and sisters, simply by being born.

So it went without saying that Rogan and I were in danger of being the most spoiled of all. What made it worse was that Rogan had trouble at school. We were in the same class. He was smart but fidgety, the nuns would yell at him for daydreaming, he couldn't focus on homework.

I helped him, reading books out loud, the two of us taking turns; not just schoolbooks but the books we read for fun. In eighth grade that year we'd read

Macbeth,

and at home Rogan and I did all the different parts, Rogan the men, me the women.

And this, too, was considered some obscure betrayal by our brothers and sisters. Since our parents couldn't be trusted to do anything, it was up to our siblings and cousins to make sure we didn't end up flouncing along North Broadway in our underwear, disgracing the rest of the clan. I had my share of black eyes and bruises, but most of these came from defending Rogan. I can see now that much of what he endured was probably the result of rampant, if unspoken, homophobia in a large family of boys and the larger tribe of male cousins. Gays weren't invented yet, not in North Yonkers anyway. You were a guy, or you were a faggot.

The irony, of course, was that Rogan wasn't gay. He was in love with me, as I was with him.

And that was maybe the only thing worse than being gay.

No one had ever heard of DNA back then, not in my family

9

anyway, and our grasp of genetics was practically nonexistent. But, because our fathers were identical twins, their children had all been told--warned--that we were closer than the other cousins.

"More like stepchildren," said Aunt Dita.

"Half-brothers and -sisters," my mother corrected her.

"Kissing cousins," said Aunt Roz. That would be the cue for everyone to cast a cold eye upon Rogan and me.

Now I waited till Michael turned to look for his brother, then I darted up behind him and kicked him squarely in the back of the knee. Michael shouted in pain and crumpled to the grass, his arm lashing out to grab me.

But I was already gone.

I knew where Rogan was--beneath Fairview. A labyrinth of storerooms, root cellars, garden rooms, and disused workshops tunneled under my great-grandmother's house. Once, they'd been tended by a small army of servants and gardeners. For the last fifty years, they'd pretty much fallen into decay. All the doors and stairways that led to the upper house had been boarded up.

Now, the only entrance was behind a thick curtain of wisteria that hung from the great porch above. You had to know where it was--a gap in the wooden trellis that peeled from the house like a scab from a wound. The wisteria looked beautiful, blade-shaped leaves and clusters of blossoms like grapes made of blue tissue. But the flowers smelled horrible, like rotting meat, and they drew clouds of greenflies and bluebottles.

Rogan wasn't afraid of the flies and wisteria. He wasn't afraid of anything.