Imagined London (5 page)

Authors: Anna Quindlen

“What, you here?” he exclaimed; “I'll bring down my work.” It was his monthly portion of “Oliver Twist” for Bentley's. In a few minutes he returned, manuscript in hand, and while he was pleasantly discoursing he employed himself in carrying to the corner of the room a little table, at which he seated himself and recommenced his writing. We, at his bidding, went on talking our “little nothings”âhe, every now and then (the feather of his pen still moving rapidly from side to side), put in a cheerful interlude.

Can this be true, writing and entertaining simultaneously? If so, the absence of effort was deceptive. Seeing Dickens's original manuscripts on view in his first house is oddly cheering; they are heavily edited by the author himself, more obscuring loop-the-loops and censorious black cross outs than acceptable prose. I remember the first time I saw the manuscript of

A Christmas Carol,

which is in the Morgan Library in New York City, and realized how hard the man was on himself and how unsatisfactory he found his first drafts. There was that thrill of fellowship; even the greatest of writers can make terrible mistakes.

T

urn off Oxford Street, that most generic of London thoroughfares, chockablock with the kind of dime-a-dozen tourist shops you can find in any American and most European cities: cheap luggage emporiums,

bureaus de change,

narrow stores that sell tee shirts and backpacks and the occasional hash pipe. Turn off Oxford Street, since there is really no reason to stay on it, and you will eventually find yourself on Baker Street. The simple utilitarian name produces a faint frisson of excitement, and your step quickens as you read the house numbers. Eventually there it is: 221.

Oh, my. A large office block called Abbey House stands on the spot, with a sign that reads: “Flexible lease available on first floor.” Next to it is a small metal plaque, much less handsome or compelling than the literary plaques on other buildings around town, with the bas-relief of a well-known profile. Note to those who have never read the books that detail the exploits of Sherlock Holmes: He didn't actually wear a deerstalker hat. Although his image on the sign does.

Every once in a while a literary location in London is so deeply disappointing that it is scarcely tenable. Dickens's house may be a little overwrought, and unless I read addresses very badly, the rooms in which Lord Peter Wimsey set up housekeeping before he married Harriet Vane are in fact precisely on the site of the Park Lane Hotel, which I suppose is as fitting a fictional bait and switch as you could imagine.

But the Baker Street location is probably the most disappointing in the city. It is not only that the apartments the legendary detective kept at 221b Baker Street, the most famous address in the mystery genre, no longer stand, those rooms presided over by the landlady Mrs. Hudson where, according to Watson, the great man kept “his cigars in the coal scuttle, his tobacco in the toe end of a Persian slipper, and his unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jack knife into the very

center of his wooden mantelpiece.” (And where the great man also “in one of his queer humors, would sit in an armchair with his hair-trigger and a hundred Boxer cartridges, and proceed to adorn the opposite wall with a patriotic V. R. done in bullet-pocks.”)

It is that, tragically, they have been phonied up farther down the street. Somehow, between numbers 237 and 241, in a gerrymander worthy of an old Chicago politician, a 221b has sprung up, complete with a young man in an ill-fitting bobby's uniform outside. (No Lestrade, this, even on his worst days!) The Sherlock Holmes food and beverage and a Sherlock Holmes memorabilia shop stand between the Beatles Store and Elvisly Yours. Across the street is another Holmes store, this one with a variety of mugs, pitchers, and a chess set with, among its pieces, a black dog that is clearly meant to be the menacing Hound of the Baskervilles but looks more like a fat lab, begging.

It's not simply that I find all of this dispiriting, but that Holmes himself, who is as vivid a character as we will find in fiction and who loathed sentiment, much less pretense, would have found it an outrage.

Luckily there are also times and places in which London is vividly, completely that place that you've encountered dozens of times in books. And it's not at the palaces, or staring at diadems in the Tower jewelry

exhibition, or even listening to some cabbie do a little mock cockney act because he's come to believe that's the sure way to get stupid Americans to ante up a big tip.

But when you've cut through one of the narrow alleys that leads from Green Park to Pall Mall, skirting the majestically restored Spencer House, wandering out onto St. James's Street, it's rather clear that you're not in Kansas, or even Manhattan, anymore. The shopwindow of Williams Evans, “gun and rifle makers,” is filled with hunting paraphernalia of the most tasteful and arcane sort, shooting coats and moleskin plus 2s and the House Tweed laird's jacket. Just up the street, a store with a beautiful assortment of top hats and bonnets trimmed with feathers and ribbons has a sign displayed near the front door: “Now Taking Orders For Ascot.”

Up on Piccadilly, the shopping arcades are as Victorian as anyone could want, with their ivory-handled shaving brushes and handmade boots. The one between Albemarle and Bond Streets is particularly atmospheric, with its enormous bay windows and gilded signs. Queen Victoria bought her riding habits in one of the shops, and it looks and feels as if the servant sent on the task had only lately left.

But perhaps it is in Simpson's-in-the-Strand that I felt most definitely ensconced in the London I'd learned to love through books, a stage-set London that

is only a highly colored, largely antiquated facsimile of the real thing. That feeling may have been inevitable, since English food plays such a central part in how Americans see England, and also how they see it in a way that is painfully out-of-date. It exists, as does so much else in English novels, in a completely foreign argot: even such a thing as tea, which we assume to be a simple beverage, turns out upon further reading to be something more, and more mysterious, perhaps with cakes, perhaps with cucumber sandwiches, perhaps with some mysterious element called clotted cream or mysterious side dish called digestive biscuits. And that is quite apart from completely foreign dishes like toad-in-the-hole or bangers and mash.

An acquaintance of mine once wrote a cookbook entitled

Great English Food,

and she said that not a single person to whom she had given it or spoken of it in the United States could keep a straight face, and some actually believed that the entire book was a joke. But it was in fact filled with the sort of food that is served at Simpson's-in-the-Strand, and was served there before any current Londoner was actually alive. (Although by London standards it is considered quite a baby; Simpson's was founded in the early nineteenth century.) You know what you're going to get when you enter its

dining room, called the Grand Divan, which features paneling as dark and glossy and plaster ceilings as richly ornamented as those in a Victorian novel of the upper classes. And if you didn't apprehend the menu from your surroundings, you can intuit it from the 1910 novel

Howards End,

in which the heroine has “humourously lamented” that she has never been thereâeven then, it was a bit of an old fogy spotâand is taken to lunch by the older man she will later marry. “What'll you have?” he asks.

“Fish pie,” said she, with a glance at the menu.

“Fish pie! Fancy coming for fish pie to Simpson's. It's not a bit the thing to go for here.”

And finally he concludes, “Saddle of mutton, and cider to drink. That's the type of thing. I like this place, for a joke, once in a way. It is so thoroughly Old English.”

And it still is. Most of the wait staff spends the lunch hours pushing around silver-domed trolleys under which are enormous joints of meat and side portions of Yorkshire pudding. It is also possible to order potted shrimps, steak-and-kidney pudding, treacle sponge, and a savoury of Welsh rarebitâin short, an English meal impervious to the passage of time or culinary fashion. Very little on the menu would be available, or even desirable, in any New York City restaurant I know. “It's a pity, really,” said one of my London book editors.

“At lunch in New York no one eats, no one smokes, and no one drinks.”

That about covers it.

Most of my London acquaintances were quick to remind me that Simpson's, although it has long had a reputation for literary lunches, was now serving them mostly to editors preparing to retire to a cottage in the Cotswolds, and that there were plenty of restaurants in Notting Hill or even around the Inns of Court that served rare tuna and mesclun salads to the younger, hipper set. But I reminded them right back that it is often at the flagrant margins that we learn to first attach ourselves to a place. That's why many of us who become Anglophiles in absentia, as it were, did so originally not through great literature, Defoe or Dr. Johnson, but through mystery stories and romantic novels, through manservants like Bunter and Lugg and heroes who gambled at Boodles and bought their boots in Bond Street.

For many Americans of a certain age, that Technicolor London first presented itself in the form of a big book about the glories of the city written by a woman who had never actually been there.

Forever Amber

was published in 1944, when the war had made satins and velvets an impossible luxury and the real world a sad, gray, and tattered place. It sold 100,000

copies in its first week and was the bestselling book in the United States during the decade after its publication. This despiteâor perhaps because ofâthe widespread denunciations of the novel by religious and civic leaders as obscene and immoral, a denunciation that seems quaint in light of today's standards for sex scenes and language.

Nominally,

Forever Amber

is a story set during the Restoration about a courtesan with the overwrought name of Amber St. Clare. Charles II is an important character, and so are a number of actual nobleman from his court. Amber is not only impregnated by the king and imprisoned in Newgate (like her more moral, more realistic fictional sister Moll Flanders); she also survives both the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London.

Like most bodice rippers,

Forever Amber

may smell of sex, but it's really about love, the undying love Amber feels, even while married to a succession of husbands and entertaining a succession of lovers, for a buff guy named Bruce, or, as she likes to call him, “Lord Carlton.” It's also about a great love affair with a great city, the city of London. Unlike the denizens of London described by Dickens, who are trapped in its narrow and filthy streets as surely as if they were behind prison walls, or those of Evelyn Waugh, who unthinkingly

pass through town on their way to one social event or another, the heroine of Kathleen Winsor's novel is beside herself with emotion whenever she considers her adopted home. “Oh, London, London, I love you,” she cries on her first day there. And that's on page fifty-three of a nearly thousand-page novel.

And the London she describes is a place worthy of that love, and still visible in spots today. There's a nice description of Amber riding out of town to snare an unsuspecting dupe in the village of Knightsbridge. While Knightsbridge is now as much a part of the main body of London as London Bridge, it is possible to walk through its side streets and small squares and understand how the great swathe of green designated for hunting by the king, later to become Green Parkânot to mention the torturous horseback travel of the dayâwould have relegated it to village status. Amber takes up lodgings at a house called The Plume of Feathers: “A large wooden sign swung out over the street just below Amber's parlour windowsâit depicted a great swirling blue plume painted on a gilt background, and was supported by a very ornate wrought-iron frame, also gilded.” Of course, any London visitor can see a similar sign hanging from any one of a dozen pubs. And the shops where Amber is seen with Bruce by his wife sound remarkably like the shopping

arcadesâodd, because the action of the novel takes place years before those arcades were built.

Or not so odd, perhaps. While I was on a trip to London, the author of

Forever Amber,

Kathleen Winsor, died at the age of eighty-three, and in a lively obituary in the

Guardian

a writer described her book thus: “It was a love letter to a London she had read about in Defoe and Pepys, but had never seen.” He went on to describe how the twenty-four-year-old American had been inspired by her husband's thesis on Charles II and had written her spectacular maiden success with the help of years of research and an enormous map of Restoration London. How odd it was to know that one of the writers who had first taught me to love Londonâbecause, given all the talk about how dirty

Amber

was, it was a must-read for teenage girls even twenty years after its publicationâwas also a writer who had fallen for the city at a distance, created it in her mind's eye, as well as on the page.

L

uckily on that visit to London I had a more historically accurate opportunity to visit its rich past. The British Museum had just opened a show on London 1753, as though someone had known I was coming and would only be able to stomach so much of Internet cafés and Starbucks lattes and all the one-world paraphernalia that has so homogenized foreign travel. The British Museum is not crowded in on the Brompton Road with the Victoria and Albert, the Natural History, and the Science Museums. Nor is it one of the gems in the necklace of important places that curves around Trafalgar Square: the National Gallery and the National Portrait

Gallery with their columns and plinths and plumes of water trumpeting their importance.

The British Museum is instead surrounded by bookstores and other small shops and houses in the midst of Bloomsbury, in such an unlikely setting that one shopkeeper a block away said that when he saw people enter with cameras and guidebooks he knew instantly to say, “Left at the end of the street, then down and it's on the right hand” even before they'd opened their mouths. Perhaps as well as any other great London institution the museum plays with the idea of how past and present conjoin. The building itself does the trick, by combining a square and stodgy classical Greek temple facade with a glass-and-steel skylit roof over the great court. The transparent roof went in in 2000 and is an absolutely magical marriage of technology, beauty, and function. (Contrary to Gershwin's “Foggy Day” lament, the British Museum has not lost its charm.) And inside the museum itself, for those of us who tend to think of the London Wall as venerable antiquity, there is the Rosetta stone and the famous mummies, as well as Greek, Asian, and Mexican treasures procured for the museum by generations of distinguished archaeological grave robbers.

So while the London show spoke to my inner antiquarian, its material was, in fact, by the British

Museum's standards, rather recent. The wonderful thing about it, however, was that it did what London, in its history and its variety, has always doneâit showed clearly that there is really nothing new under the sun.

That, I think, is one of the most valuable lessons I've learned from reading English literature, the kind of unvarying nature both of social problems and personal dramas. There is very little to separate, say, Georgette Heyer's Regency drama

Arabella,

about a young woman muddling through her long-awaited London season, from Nancy Mitford's Radlett girls in

The Pursuit of Love,

except for the passage of time and the claims of craft. Dances, dresses, men, marriage. The hypochondriacal moneylender Mrs. Islam in Monica Ali's contemporary novel

Brick Lane

may be a Bangladeshi immigrant, but she is also a Dickens character in a modern London setting. John Mortimer's hapless Rumpole, married to She Who Must Be Obeyed and drinking cheap plonk after representing yet another of the Timsonsâ“A family to breed from, the Timsons. Must almost keep the old Bailey going singlehanded”âowes a bit to Chaucer, a bit to Waugh. And all of the above owe more than a bit to real life; their like can be found in the London papers on any given day, being charged with usury, being indicted for fraud, representing those so indicted.

Most of those peering at the Hogarth engravings and Canaletto paintings in the 1753 show on its first day were aged, and so were the stories the exhibits told. Yet they were also the stories we tell ourselves every day now, to convince ourselves that the golden age is past: raging crime, class warfare, invasive immigrants, light morals, public misbehavior. Always we convince ourselves that the parade of unwelcome and despised is a new phenomenon, which is why the phrase “the good old days” has passed from cliché into self-parody. Joseph Conrad, a Polish émigré writing in English, saw this with the harshest of eyes in

The Secret Agent:

“a peculiarly London sun” is “at a moderate elevation about Hyde Park Corner with an air of punctual and benign vigilance,” and the man walking beneath it considers the gap between rich and poor, in the fashion of Conrad's highly political novels, and how “the whole social order favourable to their hygienic idleness had to be protected against the shallow enviousness of unhygienic labour.”

There's no getting away from the fact that the 1753 exhibit is full of echoes of a more modern London, as well as reflections of an older, perhaps even harsher city. Hogarth's rendering of “A View of Cheapside, as it appeared on Lord Mayor's Day Last,” looks fairly similar to Piccadilly Circus on any given Saturday night,

except for the Lord Mayor's coach and the presence of the King and Queen watching from an awninged balcony. The crush at the scene is a testimonial to what was happening then and what is happening again today: That is, that those with money and standing, who in the past had largely lived in the country and visited town only on shopping trips and special occasions, had decided instead that it was important to have a place in London. “To a lover of books the shops and sales in London present irresistible temptations,” wrote Edward Gibbon, who sold his father's country estate, acquired a lapdog and a parrot, and rented a flat in Cavendish Square, where he wrote

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

There was also, according to the exhibit's companion guide, the requisite hostility toward immigrants. They were simply different immigrants than today's Brick Lane Bangladeshis or Brixton Jamaicans. Scots, Jews, Irish, French Huguenots. There was, in the opinion of many native Londoners, something wrong with each of them, and they were certain to lower the tone and sully the streets. Many of them set up shop, but not on Bond Street, where the quality shopped, then as now.

Talk of farthingales and arsenic powder makes us also assume that fashions in dress were completely

unlike our own, and indeed the tight trousers and slashed skirts of Soho would shock and amaze any of the ladies of 1753 London. But in the British Museum exhibit, there are a pair of women's shoes as pretty as any in a Notting Hill boutique now, blue-green silk encrusted with silver lace, with a small curved heel, and alongside the shoes are some bejeweled hair ornaments, gold and silver with garnets. You could sell either in a sec in Harvey Nick's to one of those girls in tight trousers.

White's and Boodles in Mayfair were the best clubs then, not the more bohemian hangouts of modern London, the Soho and the Groucho, where, one account has it, the artist Damien Hirst was banned for being too casual about exposing himself. (Of course, literature would create its own clubs, some even more compelling. Sherlock Holmes's brother Mycroft is a member of the Diogenes Club on Pall Mall, a club in which “no member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one.” And Adam Dalgliesh, the poet who is also P. D. James's Scotland Yard superintendent, occasionally dines at the Cadaver Club on Tavistock Square, whose members are men “with an interest in murder.”)

For the working man of 1753, one great pleasure was the coffeehouse. There were hundreds of them, all doing

a booming business, although to listen to people inveigh against the proliferation of Nero's decaf take-away latte and the like, you would swear they were purely a modern invention. In the coffeehouses were the newspapers: “All Englishmen are great newsmongers,” one French observer wrote.

Which brings us to the case of Elizabeth Canning. While the London tabloids of our own time were mining the cases of two women accused of infanticide and another who had killed two young boys when she herself was a child, Elizabeth's case was the tabloid equivalent of three centuries ago, her bad press now encased in glass exhibition cases. The eighteen-year-old scullery maid disappeared on New Year's Day, 1753, and when she turned up again a month later she said she'd been kidnapped. Two old women were arrested for the crime, and both found guilty: One was branded on the thumb and sentenced to the notorious Newgate prisonâ“black as a Newgate knocker,” they once said of the lock of hair thieves wore behind one earâand the other, incredibly, sentenced to death because she had allegedly stolen Elizabeth's stays, worth about ten shillings.

When an alibi surfaced for one woman and a judge became suspicious of Canning's claims, the alleged stealer of the stays, a woman named Mary Squires

(always described in the press as “the old gypsy”) was pardoned by the king. Broadsides showed plans of the house where Canning was allegedly held, which she was apparently unable to describe accurately although it consisted of little more than two small downstairs rooms and an attic. Her portrait appeared in the papers in profile, in a cap and short cape. Another popular illustration showed Canning, who was herself tried for perjury, in the dock; the publisher exercised a master stroke of economy and, instead of using a new drawing, merely recycled the copperplate of the trial of a highwayman named James Maclaine, erasing Maclaine and having an artist draw the figure of a young woman in his place.

All of London divided into pro- and anti-Canning camps. Some gossiped that she had disappeared to hide a pregnancy and birth; others collected hundreds of pounds for her and invited her to be feted at the fashionable White's in St. James's. Her story could be transplanted wholesale into today's papers or infotainment news shows, except for her eventual punishment: She was exiled to America. Perhaps, like John Lennon, Tina Brown, and a clutch of other famous British subjects, she went on to find happiness there. Or perhaps it was a true execution by inches, as the Anglophile Henry James would have it. Near the end of

The Portrait of A Lady,

there is an exchange between Isabel and Mrs. Touchett that makes the novelist's position clear: “Do you still like Serena Merle?” the older woman asks our heroine.

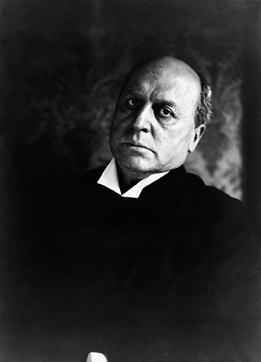

Henry James, 1843-1916

“Not as I once did. But it doesn't matter, for she's going to America.”

“To America? She must have done something very bad.”

“Yesâvery bad.”