Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (15 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Within an hour of Grant’s departure from the War Office, Stanton hurried into the building. He dictated a memo announcing his return. In his trademark peremptory fashion, he summoned the general-in-chief. For Grant, who had not expected Stanton to strike so quickly, the war secretary’s return must have seemed like the recurrence of a chronic ache. Stanton spent the afternoon in his office, receiving congratulations from happy Republicans.

But the president also wanted a piece of Grant. He demanded the general’s presence at the Cabinet meeting at noon. When asked for a report on the War Department, Grant replied that he was no longer head of that agency. The indignant president, maintaining his self-control, subjected Grant to a withering cross-examination over his “duplicity” in giving up the office to Stanton. Navy Secretary Welles thought that Grant, “never very commanding, was almost abject” until he “slunk away.” After the general-in-chief left, all in the Cabinet, save Secretary of State Seward, agreed that Johnson should have the heads of both Stanton and the general.

The tension between Johnson and Grant was ripening into a feud that would last the rest of their lives. Johnson thought Grant’s action “was that of a traitor.” When other Cabinet members sided with Johnson, Grant never again spoke to them or to their families. The next two weeks featured move and countermove between the general and the president, basted with wounded pride and resentment. Sherman tried to reconcile the two bitter men, but neither wanted rapprochement. Finally, Sherman yearned only to leave Washington.

Grant was almost as angry with Stanton as he was with Johnson. At one point, the general-in-chief set off to advise Stanton to resign, only to encounter the war secretary’s “loud and violent” hectoring. Stanton, master of the positive uses of bad behavior, was sufficiently unpleasant that Grant gave up on his mission, leaving Stanton’s office without delivering his intended message.

The general-in-chief came up with another path out of the morass. Why not, he proposed to the president, just ignore the war secretary? Johnson could order the army to disregard directions from Stanton. Johnson agreed but then never issued the order. That failure was no oversight, but a calculated measure to discomfit Grant. As the president explained to a confidant, Grant had been glad to be rid of Stanton when the war secretary was suspended. Johnson preferred to leave the two to “fight it out.”

Instead, the president again pressed Sherman to become secretary of war, a prospect that still dismayed the high-strung general. Johnson could not accept that even though he and Sherman shared political views, the general would never be adverse to Sam Grant. As Sherman had put it, they stood by each other always.

As soon as Stanton was back in the War Department, the press reported the president’s unhappiness. Johnson himself showed a reporter the minutes of a Cabinet discussion of Grant’s supposed double-dealing. The president gave exclusive interviews to a favored reporter from the

New York World

, complaining about his general-in-chief. Predictably, Grant grew furious, “as angry as any Hotspur in the land.” The general knew how to counterattack. On January 24, he wrote to Johnson requesting in writing the order that the army should disregard directions from Stanton. When Johnson did not respond, Grant raised the stakes with a second letter. Grant wrote that Johnson had said months before that he wanted to keep Stanton out of office, whether or not that was permitted by the Tenure of Office Act. As for the Cabinet meeting on January 14, Grant denied “the correctness of the President’s statement of our conversations.” In short, after accusing Johnson of soliciting his help in violating the Tenure of Office Act, Grant called him a liar.

Several advisers urged the president to walk away from the confrontation. Public opinion was against Stanton, counseled one, but “by an imprudent act you may turn it in his favor.” Another encouraged Johnson to end the impasse by appointing a new war secretary. Good advice fell on deaf ears.

Johnson challenged his top general with a letter asserting facts that were “diametrically the reverse of your narration.” He reported that every Cabinet member, “without exception,” agreed with Johnson’s version of the Cabinet meeting on January 14. Grant was not cowed. Unimpressed by the massed moral power of the president and his Cabinet, Grant replied that the “whole matter, from beginning to end, [was] an attempt to involve me in the resistance of the law, for which you hesitated to assume the responsibility in orders, and thus to destroy my character before the country.”

At this point, Congress demanded copies of the incendiary correspondence, which promptly appeared in newspapers across the land. The episode was fascinating and horrifying: the president and his military chief exchanging angry accusations of mendacity. Even some who disliked Johnson doubted Grant’s version of events. Such doubts, it turned out, mattered little. The public was going to believe its hero general, not its president-by-accident. Early on, the

New York Tribune

distilled the calculus:

In a question of veracity between a soldier whose honor is as unvarnished as the sun, and a President who has betrayed every friend, and broken every promise, the country did not hesitate.

Grant’s successful campaign against Johnson in the winter of 1868 resembled some of his military operations. Somewhat surprised to be drawn into battle when the Senate reinstated Stanton, Grant made a swift, visceral evaluation. Whatever he might have said to the president before, he could not violate the Tenure of Office Act. Intentionally breaking a law, even a dubious one, would place him on the low ground. Worse, it would turn him into Andrew Johnson’s toady. While the president dug in his heels, seething and glowering, Grant explored ways to resolve the dispute, including appointing Governor Cox as war secretary, or bypassing Stanton at the War Department. When Johnson showed no interest in resolving the impasse, Grant attacked, throwing his massive popularity against the president’s checkered reputation. It had not been elegant, but it got Grant out of a tight political corner with his reputation mostly intact.

Thaddeus Stevens watched the contest closely. When the House clerk read aloud Grant’s letter to Johnson of February 3—with several interruptions for spontaneous applause—the ailing congressman from Pennsylvania smelled blood. Grant, he exulted, “is a bolder man than I thought him.” With this evidence, Stevens continued, “Now we will let him into the Church.” Best of all, Grant gave Stevens a fresh theory for impeaching the president: that he had solicited Grant’s violation of the Tenure of Office Act. Within days, Stevens was pressing that theory in another impeachment resolution.

By February 10, Stevens was ready. He persuaded the House to transfer all impeachment records to the Committee on Reconstruction, which he chaired. Now the Pennsylvanian could control the process.

The president did not sit quietly and wait for Stevens’s next step. On the night before Stevens was to bring his resolution to the House, Johnson granted another interview to a friendly reporter. The president’s performance had a Jekyll-and-Hyde quality. He presented himself as calm and aloof from the storm. When impeachment came up, the president “laughed as if he didn’t believe the charges would ever come.” Johnson shared his unusual notions of political economy, blaming the nation’s economic troubles on emancipation, which converted slaves from “a good [that] increased the productive resources of the nation” into freedmen who burdened the country.

But the heart of the interview was an assault on General Grant. The general supported the president during his early months in office, Johnson stressed, and had opposed Negro suffrage. Grant’s suggestion that the president order the army to ignore War Secretary Stanton was now, for Johnson, “only one of a great many instances in which [Grant] has grossly deceived me.” After brandishing correspondence from Sherman to buttress his position, Johnson dismissed Grant as just another politician, the “Radical candidate for the Presidency.”

But Johnson could not let go. On February 10, he fired off yet another rejoinder to the general, sputtering about Grant’s “insubordinate attitude.” A day later, Johnson released letters from Cabinet members supporting his version of events. Yet the president took no action against the general-in-chief, effectively admitting his mortifying political weakness. As summed up by old Thomas Ewing, General Sherman’s father-in-law and longtime political power, Grant’s actions “made it incumbent upon the president if he had any actual power to court martial him, but…he has not.”

For Stevens, both sides of the Grant-Johnson correspondence established that the president tried to induce Grant to violate the Tenure of Office Act. As Stevens put it, “If the President’s statement is true, then he has been guilty of a high official misdemeanor. If the General’s statement is true, then the President has been guilty of a high official misdemeanor.” There was enough, he insisted, to impeach a dozen men. As for “the question of veracity, as they call it,” Stevens invited the two men to “go out in my back yard and settle it alone.”

Stevens presented a new impeachment resolution to his committee on February 13, along with a report charging Johnson with soliciting the violation of the Tenure of Office statute. Though Stevens was “very earnest,” his committee balked. “Old Thad is still firm,” one reporter wrote, “but the others flinch.” Moderate John Bingham of Ohio held the balance of power. He moved that the resolution be tabled. His motion won, 6 to 3.

Once more, Stevens declared the Republican Party full of cowards. Once more, he pronounced impeachment dead. Once more, Johnson had survived. No matter how many ill-advised quarrels the president picked, no matter how many apparent blunders he committed, Stevens could not find the formula for a successful impeachment. Not enough Republicans shared his view that impeachment was a political tool for removing a woeful president like Andrew Johnson. And now Stevens could not even get an impeachment resolution out of his own committee. His failure was so plain that Samuel Clemens published a labored spoof portraying Stevens and other Radicals as nurses forced finally to admit the death of “our brother, impeachment.”

If he could not get rid of the man in the White House, Stevens resolved to cut off even more presidential powers. “[T]hough dying,” Clemenceau wrote, Stevens “proposes more bills in one day than any of his colleagues in a month.” He proposed to give General Grant unfettered control over Reconstruction in the South, a power that Grant did not want. Another bill aimed to limit the president’s recourse to the courts by requiring a two-thirds majority of the Supreme Court before a law could be declared unconstitutional. Stevens’s Reconstruction Committee was preparing legislation to readmit individual Southern states to the Union. Even without impeachment, there was plenty to do.

With the failure of this latest impeachment effort, Johnson’s thoughts turned to revenge. After seven months of scheming, he still was saddled with Edwin Stanton at the War Department. And now he had a serious score to settle with Ulysses Grant. A reporter who visited the White House found the president looking “as if he would like to raise…perfect hell.” Indeed, the reporter continued, “he expects to crush his enemies.”

That vindictive spirit blinded Johnson to the damage he was doing to his own cause. Why not appoint a secretary of war whom the Senate would confirm? Even if such a candidate were far from his first choice, he would certainly be preferable to Stanton. But Johnson had no appetite for compromise. Indeed, he had achieved the implausible feat of making Stanton, perhaps the most disliked official in Washington, an object of sympathy. To many Americans, the president no longer seemed like the nation’s leader, but rather like a man obsessed with settling personal scores.

FEBRUARY 15–21, 1868

The President called upon the lightning and the lightning came.

C

LEMENCEAU,

F

EBRUARY

28, 1868

G

ENERAL SHERMAN PLAINLY

was the answer to Johnson’s problems. Of the Union Army heroes, Sherman was second only to Grant. After two years as Grant’s senior corps commander in the West, the general called “Uncle Billy” by his admiring soldiers had driven an army across the South, captured Atlanta, and conducted his famously destructive and demoralizing march to the sea.

But Sherman was not only a Northern hero. He also was strongly sympathetic to Southern whites. Before the war, while superintendent of what is now Louisiana State University, he grew fond of Southern ways and people. Though he was a remorseless battlefield foe whose name would be reviled by generations of Southerners, he was a generous victor. In North Carolina shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, Sherman accepted the surrender of the last major Confederate army in the field. His terms were so magnanimous that War Secretary Stanton denounced them to the press and Grant had to hurry to North Carolina to retract them.

The red-bearded Sherman was no fan of congressional Radicals or racial equality. He did not want blacks in his fighting corps, preferring a white man’s war. “With my opinions of negroes and my experience, yes, prejudice,” he wrote, “I won’t trust niggers to fight.” After the war, he thought blacks should be free, “but not put on an equality with the whites.” Called a race-hater by one Northern newspaper, Sherman thought the Radicals were trying to foment a new civil war. He supported Johnson’s 1866 vetoes of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and the Civil Rights Act. One Cabinet member hailed Sherman as a conservative opponent of the Radicals.

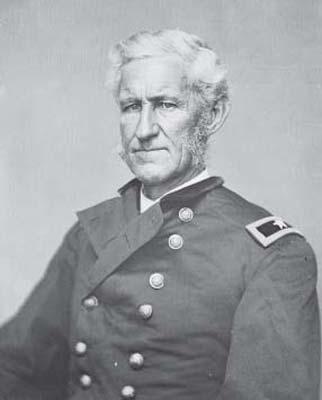

Lieutenant General William T. Sherman.

Sherman’s powerful family connections would guarantee Senate confirmation of him for any appointment. His brother, John, was the junior senator from Ohio, a Republican not usually counted among the Radicals. His father-in-law, Thomas Ewing, had been a senator from Ohio, plus treasury secretary in the early 1840s and interior secretary in the early 1850s. Ewing also was Sherman’s surrogate father. When Sherman’s own father died, leaving a widow with eleven children, Ewing took in nine-year-old Tecumseh Sherman, gave him the first name William, and raised him with his own children. Ewing was a Washington power broker still. Johnson’s attorney general, Henry Stanberry, had been Ewing’s law partner, while Ewing also sponsored Interior Secretary Orville Browning.

From Johnson’s standpoint, Sherman seemed too good to be true. Which, it turned out, he was.

Many high-ranking soldiers profess a disdain for politics but are drawn to it by ambition, or by a sense of duty, or a mixture of the two. Not Sherman. His horror of the political world was unshakable. “Washington is as corrupt as Hell,” he wrote to his wife in May 1865. “I will avoid it as a pest house.” Moreover, Sherman would never allow himself to be used against Grant. Twice already, the volatile Sherman had deflected Johnson’s efforts to raise him above Grant.

As January ground to its acrimonious close, the president contrived a new set of lures designed to overcome Sherman’s resistance. Johnson offered to create a military district for Sherman—the District of the Atlantic—that would include Washington City, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and West Virginia. Though Sherman might dread Washington, the president knew that Mrs. Sherman longed to be in the nation’s capital, close to her father and brothers. Johnson also proposed to appoint Sherman “Brevet” (or temporary) General of the Army, placing him at the same rank as Grant and making him the third officer in American history (after Washington and Grant) to hold that rank. Then Johnson would name him interim war secretary. Stanton would be gone for good, Grant would be subordinated to an officer he liked and respected, and Johnson would be able to sleep at night.

In a passionate letter, Sherman declined the offer, arguing that it would guarantee conflict among the president, Grant, and Sherman. He underscored his personal wish to be nowhere near Washington, pointing to the city’s impact on Grant:

I have been with General Grant in the midst of death and slaughter…and yet I never saw him more troubled since he has been in Washington, and been compelled to read himself a “sneak and deceiver,” based on reports of the four of the Cabinet, and apparently with your knowledge. If this political atmosphere can disturb the equanimity of one so guarded and so prudent as he is, what will be the result with me, so careless, so outspoken as I am?

Sherman closed with more sound advice for Johnson. Since Stanton had no actual power now, he wrote, Johnson could afford to leave him in office to perform empty ministerial duties. Sherman also warned Johnson not to use force against Stanton, a prospect that the president evidently had raised.

Johnson suffered a serious fit of indecision over what to do with this balky general. The president was firm to the point of obstinacy once he made up his mind, but he could hesitate before major decisions. His loyal navy secretary thought this his greatest weakness. On February 6, Johnson ordered the creation of the Department of the Atlantic with Sherman in charge. The next day, he withdrew the order. One day later, he changed course again, directing preparation of an order creating the new district but not naming Sherman as head of it. Johnson finally issued the order on February 12, directing that Sherman command the new district. On the day after, he nominated Sherman as brevet general.

Sherman was wild when he learned of the president’s actions. He thought first of resigning from the army. To Grant, he likened the president’s order to “Hamlet’s ghost, it curdles my blood and mars my judgment.” To his brother the senator, Sherman complained that Johnson “would make use of me to beget violence.” He asked his brother to oppose his promotion in the Senate. Once more, Sherman pleaded with Johnson to abandon his plan. When Johnson received Sherman’s protest on February 19, he finally gave it up.

Yielding to Sherman’s wishes meant that the president would need another strategy for driving Stanton from the War Office on Seventeenth Street. Johnson was in a permanent state of barely suppressed rage. He had endured the disloyalty of Stanton and Grant for too many months. Twice he had watched Congress dismantle his Southern policy. He had survived thirteen months of impeachment investigation and two serious attempts to impeach him. His fury was past the bursting point. He had had enough.

On Sunday, February 16, President Johnson went to church with his personal secretary, Colonel William Moore. Back at the White House, Moore read to the president from the drama

Cato

, written in 1713 by Joseph Addison, about the Roman aristocrat who resisted Julius Caesar’s grab for power. The play, with its confrontation between despotic evil (Caesar) and republican virtue (Cato), was a favorite of Americans in the colonial and revolutionary eras. George Washington fell in love with it at age thirteen. To buoy his troops’ flagging spirits during the brutal winter at Valley Forge in 1778, Washington had his officers stage

Cato

. The play features little action, characters that can only aspire to be two-dimensional, and relentlessly self-righteous cant. It has slid out of favor with modern audiences. For President Johnson, it was pure inspiration.

“Cato was a man,” he instructed Colonel Moore, “who would not compromise with wrong but being right, died before he would yield.” Johnson pointed out that Caesar offered peace terms to Cato, “but proud old Cato folded his arms and sustained alone by his sense of duty to Rome, dictated…terms to Caesar.” Needless to say, Cato dies at the end of the play.

Johnson, Colonel Moore concluded, “[w]ithout directly expressing the thought in words,…intimated a parallel between his position and that of Cato.” Moore thought the president saw himself similarly devoted to pursuing the right; Johnson also could seem indifferent to the consequences of his actions, evidently wishing for martyrdom. In a newspaper interview in early February, the president made the point himself. “He said the time had arrived,” the

New York Evening Post

reported, when he would be “compelled to ignore the Constitution itself or [ignore] an act of Congress [the Tenure of Office Act] clearly unconstitutional.” He would not hesitate to uphold the Constitution, Johnson promised, at the risk of impeachment. Navy Secretary Welles wondered if the president courted impeachment, a glorious political death to rival Cato’s.

The next day, Johnson sent Colonel Moore to see John Potts, the chief clerk of the War Department. By statute, Potts was to run the department when there was no Secretary. Moore offered Potts the chance to become interim war secretary. Potts could then demand the papers of the department from Stanton; if Stanton resisted, Potts could sue Stanton for control of the department.

“Mr. Potts,” Moore recorded, “shrank from this.” Understanding Stanton better than the president did, Potts pointed out that the war secretary would simply fire him as chief clerk. When Moore argued that Stanton would no longer be Secretary and thus would have no power to fire him, Potts was not convinced. He knew Stanton. Potts’s refusal disappointed the president. If he could only find the proper man to replace Stanton, Johnson mused, “he would settle the matter this morning.”

Anticipating that both Potts and Sherman might be unwilling, the president had cultivated a third candidate, Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. At a meeting with Thomas on February 18, Johnson raised the possibility of placing the adjutant general as interim war secretary. The soldier was willing. Then General Sherman’s letter arrived with its plea to be spared Washington duty, and Potts scurried out of the picture. Johnson turned back to Lorenzo Thomas. Moore, the president’s aide, questioned whether a Thomas appointment would “carry any weight.” The president admitted it would not, but his patience was at an end.

[Johnson] said he was determined to remove Stanton. Self respect demanded it and if the people did not respect their Chief Magistrate enough to sustain him in such a measure, the President ought to resign.

But for this unlucky intersection with Andrew Johnson in high dudgeon, Lorenzo Thomas would be remembered, if at all, as a diligent army officer for more than forty years. An 1823 graduate of West Point, he was adjutant general when the Civil War broke out. With power over the army’s personnel matters, the adjutant general had to be politically deft, particularly with senior officers. Thomas did well enough in the job until Stanton took over the department in 1862. The brusque new Secretary had little patience for the avuncular Thomas, a tippler who was fond of dress uniforms. One contemporary recalled Stanton pledging to “pick Lorenzo Thomas up with a pair of tongs and drop him from the nearest window.”

Stanton never flushed Thomas out of the army, but he stashed the older man out of sight for five years, beginning with an assignment to recruit black soldiers in the Mississippi Valley that kept Thomas on the road for the last two years of the war. After the Confederate surrender, Thomas’s exile included inspections of military offices and national cemeteries. His able second-in-command acted as adjutant general during his extended absence.

Army Adjutant-General Lorenzo Thomas.

Thomas finally returned to Washington in late 1867 to write up his report on the cemeteries. With Stanton suspended from office, Thomas seized several opportunities to ask President Johnson for reinstatement as adjutant general. No doubt the president knew of the bad feeling between Thomas and Stanton. That hostility only commended the adjutant general to the president. Even more gratifying to Johnson, Grant also had little affection for the adjutant general, recently recommending his involuntary retirement. On February 13, the president directed that Thomas be reinstated as adjutant general, then a few days later sounded him out about the War Department appointment.