Imperial (18 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Now the hills of bamboo and grass on either side resembled the Everglades. Four black-winged pelicans flew together over the grass. The sunken chocolate windings of the New River seemed to get richer and richer. But presently another odor began to thicken, the familiar stench of North Shore, Desert Shores and Salton City.—The sea’s right on the side of these weeds here, my guide was saying.

What’s that smell, Ray?

I think it’s all the dying fish, and dead fish on the bottom. It forms some kind of a gas. It’s just another die-off. It’s natural.

Ducks flitted happily, and then we saw ever so many pelicans as we arrived at the mouth of the Salton Sea. Were the birds contented here or did they just have to take what they could get, since ninety-five percent of California’s wetlands were already gone? I could see Obsidian Butte off to the right, and then the promontory of what must have been Red Hill Marina. How many dead fish did I spy around me on that day? I must be honest: Not one.

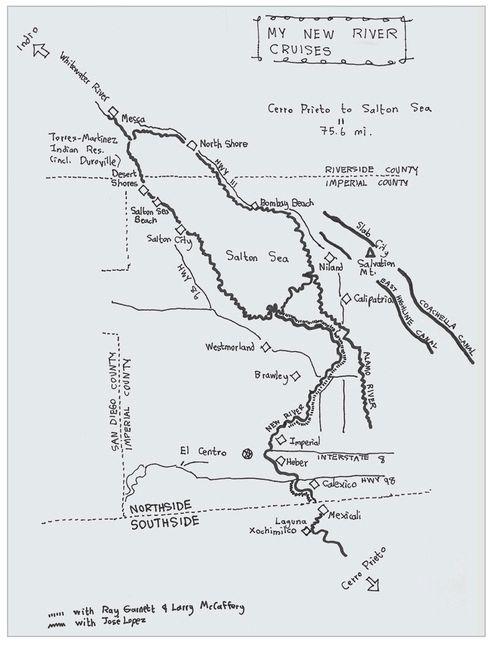

Jose Lopez on the New River, 2001

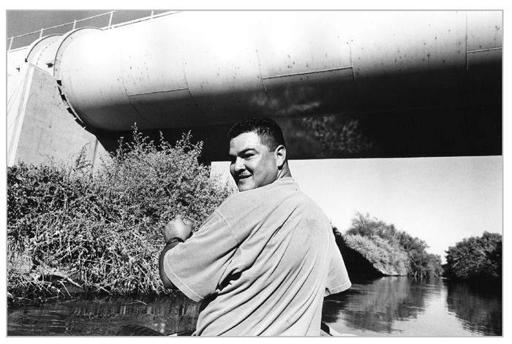

Ray Garnett on the New River, 2001

You get away from the smell when you get out here fishin’, said Ray, and he was right, for far out on the greenish-brownish waves (that’s algae bloom that made the water turn green, he explained. So there won’t be any fish in here today. You don’t fish in here), the only odor was ocean.

They’ve had studies and what have you ever since the late fifties, he sighed.

And did they conclude that water quality was getting worse?

That’s what we thought in 1995 when we put four hundred and twenty hours in and didn’t catch a fish. In ’97 and ’98 they started coming back. Whether the fish have gotten more tolerant or whether it’s something else, I don’t know.

It was pretty salty out here, all right. The Department of the Interior had announced that the sea’s ecoystem was doomed unless nine million tons of salt could be removed every year. In the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s yearbook for 1909, an article entitled “The Problems of an Irrigation Farmer” explains the necessity for adequate drainage to carry away the salt from cropland which like all the Imperial Valley once lay under some primeval sea; simply irrigating the soil is not enough, for as the evaporating water rises up through the topsoil, it draws dissolved salts with it, leaving the poor sad irrigation farmer ever more worse off. (Much of this book chronicles the continuing defiance of that principle.) What to do? Watch for creosote bushes if you can; they’re a sign of low alkalinity. But if your homestead happens to lack those vegetable signals, you’ll just have to flush out the soil, draining and draining, dispatching salt downward; and, as we know, the lowest point of the Imperial Valley just happens to be the Salton Sea.

Sabine Huynen of the University of Redlands Salton Sea Database Project had told me: The Salton Sea contains ninety-nine percent salt.

That sounds rather clean, I remarked.

There are very small traces of pesticides that are in the sea itself. The only places you find higher levels are in the bottom sediments. As of now there are no major issues in terms of pollutants. It used to be a lot worse. Due to pesticide regulations, the water quality has improved.

Would you feel comfortable drinking New River water near the sea’s mouth?

She laughingly replied: Aside from the salt, yes.

Deep in a choppy orangish-green wave, Ray thought it best to turn around. As we approached the New River we grounded on a sandbar.

There were actually three of us in the boat: Ray, myself, and my friend Larry from Borrego Springs, who now in his autumnal years was becoming a natural history enthusiast. He’d come along for the adventure. Ray announced that somebody had to get out and help him push. I stared at the sores on my ankles which had arisen during the cruise with Jose, and while I stared, good old Larry leaped into the water; but my selfishness was all for nothing, because we were still grounded.

If you don’t mind getting your feet wet, said Ray to me, it sure would make things easier.

We pushed. The water seemed to sting my feet, but that time I was most definitely imagining things.

Brown pelicans accompanied us overhead as we motored slowly upriver; then there were some bubbles, possibly from pollution or some geothermal source. A jackrabbit crouched on the bank. Now came again the lush, low banks of Westmorland, and up on either side the flat green fields to whose crop yields this river had in part been sacrificed (as the fellow from the Audubon Society told me: Nine million pounds of pesticides a year on Imperial Valley fields have got to go somewhere!), birds under concrete bridges, smoke trees, a fire pit, made perhaps by illegal aliens, beer cans, toilet paper, birds’ nests, tamarisks, which choke out anything, and a dead palm trunk. The New River was turning chocolate-green again. Upstream of our starting point the water grew paler and creamier, greener and foamier than ever, with clots of detergent-like froth merging with the mysterious bubbles. Meanwhile, on the bank near a wall of seasoning hay bales, a man stood, getting ready to fish.

Must be something wrong with this water, said Ray, ’cause I don’t see any bullfrogs. I been watchin’ the bank. I seen a lot of ’em in the canals, but not a one here. No turtles, either. Bullfrogs and turtles can live in anything.

Now came a sickening sweet stench of rotting animals. That stench went away, but presently I got a sore throat and my eyes began to sting. I didn’t ask Ray how he was doing. And presently we came to a burned, half-sunken bridge; it was too risky to try to get past it, so that was the end. My feet kept right on tingling. With a kind and gentle smile, Ray gave me an entire bag of smoked corvina.

“IT’S PROGRESSING ALONG REAL NICE” (PART ONE)

No face which we can give to a matter will stead us so well at last as the truth.

That is what Thoreau wrote while he was measuring and meditating upon Walden Pond. He continues:

For the most part, we are not where we are, but in a false position. Through an infirmity of our natures, we suppose a case, and put ourselves into it, and hence are in two cases at the same time, and it is doubly difficult to get out.

Throughout my researches into the state of the New River and the Salton Sea, I found myself similarly in two cases at the same time, for once not so much thanks to my own fault as thanks to the errors and self-serving claims of others. But my fault did lie in this: I had drunk in a certain doctrine, whose sources are as obscurely ubiquitous and whose substance is as tainted as New River water, that only an “expert” has the right to judge the acceptability of the water of life. The Salton Sea is a dying sump or the Salton Sea is the most productive fishery in the world. (At Red Hill Marina a sign announced that as of A.D. 2000 all corvina taken must be at least eight inches long; there was no limit on sargo.) The New River is the most polluted watercourse in the United States, perhaps in North America, or the New River is—well, not virgin, but if its degree of purity became irrelevant, could we not then exhume ourselves from our double case, especially since ever more of its Mexican length is getting interred? And it bears merely ten percent of the Salton Sea’s inflow, or thirteen percent, or whatever, so it must be nearly innocuous; moreover, the worst toxins are safely hidden in its sediments . . . The only way I could think of to decide the matter was to abrogate my own judgment, paying technicians to analyze one water sample from the river and another from the sea, in order to ascertain whether any pollutant happened to exceed standards which other technicians had decreed were acceptable. Then I’d know, because a printed report would tell me.

Can I say that Ray Garnett knew? His criterion for deciding that the New River must be in trouble was the absence of bullfrogs and turtles. He’d made up his mind; he was not straddling two opposing cases! But he’d also made up his mind about the Salton Sea, and I wasn’t sure that I could agree with him there. Where lay my mind?

We suppose a case, and put ourselves into it.

It would be in my interest as a hack journalist to write something horrific about the Salton Sea or the New River. I’d supposed a case, the worst case, and on the basis of that supposition, a magazine had paid me to lower myself into the case and write this chapter of

Imperial;

wouldn’t the magazine’s readership be disappointed if the laboratory’s numbers turned out to be ordinary? Well, the Salton Sea Authority would not feel disappointed at all.

Not having even collected my samples yet, I still knew the truth. The Salton Sea is ghastly. The New River is ghastly.

We might say that the sea, having been created by an engineering accident, was nobody’s fault. Nor can anybody be held accountable for the fact that prior to the floods the Salton Sink had already glared and glistened with saltbeds.—Tom Kirk told me: Our salt levels are about twenty-five percent higher than the ocean and we support a marine environment that’s pretty robust here. If the levels go up, we’ll lose the fishery, then the shorebirds, then the benthic organisms.

The levels were going up, no question about that. The Alamo, Whitewater and New rivers submissively accepted the runoff from ever so many salt-flushed fields.

Maybe the New River wasn’t anybody’s fault, either. People need to defecate, and if they are poor, they cannot afford to process their sewage. People need to eat, and so they work in the

maquiladoras—

factories owned by foreign polluters.

25

The polluters pollute to save money; then we buy their inexpensive and perhaps well-made tractor parts, fertilizers, pesticides.

It is doubly difficult to get out.

And it’s all ghastly.

“IT’S PROGRESSING ALONG REAL NICE” (PART TWO)

The New River flows into what is not quite the southernmost extremity of the Salton Sea. Four miles due west, one strikes the other shore (where SUNKEN TREES adorn the map). Then it’s a straight shot halfway up the sea to Salton City, followed by Salton Sea Beach where Ray lives, then the nearly defunct Sun Dial Beach, and finally Desert Shores, where beside the rickety dock, stinking white fishes gaped in the sun, some of them swirling with each greenish-brown wave (an algal bloom had struck), others washed farther up onto the boat ramp (ANNUAL LAUNCH FEE $25. See Manager), the rest squashed into the pavement. Halfway down the dock, which nearly broke under my weight, I gazed into the Salton Sea and saw a great fish split open like a sack; beneath the strips of its putrescent flesh, vermin were nuzzling like babies.

A couple backed their boat down the launching ramp, the man steering, the woman craning her head with extreme seriousness. Fish-corpses squished beneath their wheels.

See Manager, the sign had advised, so I went to see the manager, Mr. David Urbanoski, who’d lived in these parts for twenty years.

What’s the state of the sea right now, Mr. Urbanoski?

It’s progressing along real nice, he said. They’ve got desalting ponds goin’ in, and there’s another company that’s putting desalting plants in . . .

Well, I’m happy to be back here, I told him. I don’t come to Desert Shores so often, but every year I take pictures in Salton City, down by where the yacht club used to be.