Imperial (25 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

An undated aerial photograph depicts an S-curve in the desert with a crane at the end of it, then sand and scrub all around. It will be eighty miles long. Every time I see it, I can’t help but use the trite word

miraculous,

because it is so blue and cool as it speeds through the white hell of the desert. (Here come the blue-green rushings of the East Highline Canal through its locks.) Stripes of tan, stripes of emerald all the way to the haystack-horizon, they represent no mere infinity, but the conquest of infinity!

AN ESSAY ON URINE

Next issue:

With our magnificent water system (the pure fresh water coming from the mountains of Wyoming) and with our unparalleled drainage, which carries all undesirable matter toward the Salton sink, we need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

These founders of American Imperial see “drainage,” which is as necessary, hence as unobjectionable, and therefore as non-unpleasant, as the stream of urine which issues from each of us from time to time; I for my part see a stinking stream shaded by a freeway overpass and a railroad overpass, accompanied by grass, paper cups, plastic bags, litter and a drowned shopping cart as it flows toward the Salton Sea; and probably the founders are right and I am wrong, because the particular manner in which urine stinks remains irrelevant to its purpose. Cross the border, and ten minutes south by foot, just in front of the Playboy Club, there’s a taco stand illuminated by bare bulbs, and around its bowls of watery green sauce, bloody angry red sauce, spicy beans and delicious pickled onions, the street-whores, tired vendors, excited children and passersby are gathered to eat while listening to the meat cleaver’s rhythmic fall. A few steps to the westward, the aroma of fresh tortillas stales, then mingles with the smell of sewage, for we’re overlooking the Río Nuevo, whose

aguas negras

wriggle horridly down there in that shantytowned gorge that the Colorado River made when it made the Salton Sea. (So it is in the year 2000. Next year they’ll cover that cloaca over, in order to hide the stench; then it will vanish out of mind, becoming the merest “drainage” again.) Irrelevant! In the west, the sky’s afire in the narrow strip between mountain and cloud, and that fire resembles the brown and black and gold of roasted Mexican corn; that’s irrelevant, too, but don’t think that the

Imperial Press and Farmer

will neglect it—oh, no, not these pages of smug booster-ism whose repeated commonplaces (irrigation is cheaper than rain; grow alfalfa to increase the weight of your hogs; the businessman is known by his stationery; don’t trust to luck when you are able to work; every crop on earth will grow in Imperial if you only buy it through the Imperial Farmers’ Store) become as flat and dreary as the desert of those parts, for the

Press

is a company paper, the mouthpiece of the Imperial Land Company. Thank God some oases of jokes have been provided: the man who swears his love

by those lofty elms in yonder park

unnerves his sweetheart,

because those trees are slippery elms,

and whenever we get sick of him, we can laugh at the lethally incompetent doctor, the burglar who can’t pull open the bedside drawer because humidity has warped it, the scolding woman, the effete woman, the spendthrift, the watermelon-stealing Negro,

37

the grasping proprietor of the “Jew store.” Don’t worry; I promise that these jokes will never get racy; you’re on Northside, where we are or pretend to be as prudish as the characters in

The Winning of Barbara Worth,

since

no desert is a fit place for an idle or dissolute man.

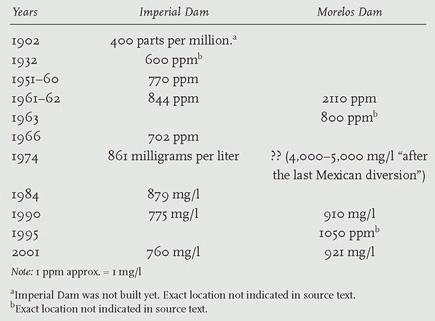

Meanwhile, pure Colorado water, magnificent water, I mean, the Nile of America, enters Imperial’s ditch-veins and percolates through the fields, nourishing cantaloupes, onions, date trees, grapefruits, alfalfa-heavens; it’s a bit more turbid now, more saline with the wastes of those transactions; but other ditches playing kidneys’ parts permit lucky Imperial to urinate endlessly, infinitely, I mean, right into the New River and the Whitewater and the Alamo, thence into the Salton Sea, whose salinity was three thousand three hundred fifty parts per million in 1905; in 1931 Mr. Otis B. Tout confided to his readers:

It is a surprise to many people today to find the waters of Salton Sea drinkable, although brackish;

in 1950 the salt content, now equalling that of ocean water, was almost ten times higher than the 1905 figure; in 1974, eleven and a half times greater; in 2001 it was nearly fourteen times more.

Excuse me, but you’re not against pissing, are you? What the Regional Water Control Board’s engineer, Jose Angel, said to me about the Salton Sea has already been accepted without reservation:

What can we do? Because fertilizers have a legitimate agricultural use.

—Moreover, I quote from the Executive Summary Report of the Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Forum (1984):

The Forum finds no reason to recommend changes in the numeric salinity criteria at the three lower main stem stations.

Speaking of legitimate agriculture, the Colorado River may not be quite as mountain-pure as they say, but, as might be expected, the

Imperial Press and Farmer

offers reasons why that is actually advantageous:

The waters of the Colorado river carry a very large amount of commercial fertilizers . . . a tract of land irrigated during the season with water enough to cover the ground three feet deep would receive fertilizers to the value of over $10 per acre.

If only those complainers down in Mexicali would see it that way! Salt’s a fertilizer, too, isn’t it?

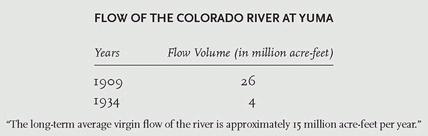

SALT CONTENT OF COLORADO RIVER WATER AT THE CALIFORNIA-MEXICO BORDER

Imperial Dam (constructed in 1938) is the last diversion site in the U.S.A. Morelos Dam (built in the middle of the century) is the first diversion site in Mexico. The greater salinity at Morelos results from what we euphemistically call “irrigation returns.” The peculiar dip in salinity for 1963 may be the result of my placing it in the wrong column; I am guessing at Morelos Dam since the study is Mexican.

Sources:

Colorado River Board of California (1951-62); Morton (1977; 1966 data); Philip L. Fradkin (1974); Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Forum (1984); Gerardo García Saillé et al (1990, 2001); Francisco Raul Venegas Cardoso (all other dates).

Again the word

irrelevant

blows across Imperial to me; my own time, the time they pretended they were doing it all for, could not have mattered to those pioneers as much as they pretended; the future they built for was their own; and in their now bygone time they, the Colorado River’s self-adopted children, could never suckle their mother dry. Just as Salton City spreads out in the sand, each house, boarded up or not, comprising a single grain of cosmic dust in the universe, they themselves remained atoms in desert emptiness. What would they have made of Salton City? At Riviera Keys I tread on crusts of salt and dead fish; I observe an egret brooding on one leg, a garlicky stench of decomposition. This part of Salton City, like the others, is still and grey, the stench interrupted only occasionally by bird-cries.

What do you do for fun?

Ride around on my dirtbike, replies the fourteen-year-old.

Does the smell bother you?

We’re used to it, he says, as proudly as anyone. Besides, I don’t never go down there.

Irrelevant! Don’t tanneries likewise stink? Reclamation justifies such inconveniences.

The green things growing are improving every shining hour, and making the farmer’s heart glad . . .

writes Judge Farr.

The nights are always cool, affording restful sleep, while the sleeper dreams of his rapidly ripening fruit and their early arrival in the markets to catch the top prices ahead of other competitors in less favorable regions.

THE COLORADO’S MOUTH (1775, 1796, 1827, 1845, 1895, 1903, 1910, 1925, 1950, 2002)

Passing the wrecking yard whose cars are the color of the desert earth, I leave Mexicali to the north of me. Stackyards, failed restaurants, propane trailers and tire fences decay infinitesimally upon this blank flat red desert land. A hand-painted sign announces that CARNE ASADA will be available in 100 Meters. But it isn’t. Ten kilometers from San Luis Río Colorado, I see lush green fields of sugarbeets, water spewing silvery out of a pipe’s throat, spilling luxuriously on the ground. The way that Mexican children play around open water emblematizes for me Imperial at its best: Water comes, and there is life, laughter. And I continue east. Here’s a whole family bathing in an irrigation ditch beneath a pump of cold water. (Pests, said a Mexican rancher. Sometimes they leave broken bottles around. Then I fence it off.) Imperial grows dry again now. Here’s the yellow bridge over the bush-lined Río Colorado, which seems to be paralleled by a canal. I cross the bridge and pass out of Imperial. Through the rearview mirror, I see that thin but fairly deep snake of a river turning south, toward the Golfo Santa Clara, for which I now find a sign. This way! Here’s a cross, a concrete-lined irrigation ditch and then a roadside shrine for another accident victim, a silver-blue mirage in the black road, an ocher irrigation channel captioned by a beer bottle which glints by the side of the road as brightly as any flare. Here comes a field of something dark green-grey, then a tiny American-style field of alfalfa crowned by neatly staggered emerald bales. An unfinished (still roofless), turquoise-painted homestead secluded within a grove of carefully planted young palm trees makes me wonder what it would be like to live here; then the paved road becomes dirt, and the dirt gets too rough for the rental car. The Gulf may be this way, but all I can see is red dirt at fieldside, then a garbage dump, a green-choked ravine, a wide, white-sanded canyon.—Where’s the Colorado?—Farther west, I suppose, past these old stoves and refrigerators and smoke trees, this toilet paper spotted yellow and brown, these paper plates. Everything has been too thoroughly sun-dried to stink very much. I turn around, re-encountering those black-burned palm trees with ornate fronds, that swaggering-looking scarecrow in a cowboy hat. Here stands a family in roadside shade, the children hooking up their shirts to expose their bellies to coolness, the wrinkled old mother staring fixedly across the road into nothingness. And the road goes on into San Luis Río Colorado, a hot town, an Imperial town, “a colorless town with a growing number of

maquiladoras,

” a town which feels wider and lower than Mexicali.

Here at the border the Colorado comes green-grey through a narrow gap in the wall, which must be as high as at Mexicali but seems less impressive; the boys in baseball caps and the tattooed boys make the snake and flow over it while the white Bronco idles on the Arizona side, its Border Patrolman waiting for them to come close enough for him to roll down his window, stick his hand out of the air-conditioning, and gesture them back into Mexican Imperial; and they obey; it was all in fun. That is on the north side of this uneven little bridge under which the Colorado flows. On the south side there’s a narrow reed-grown dirt path alongside hanging laundry. And the Río Colorado runs by, narrow but deep, maybe even chest-deep; I don’t believe I could jump over this river, not quite. What does my 1910

Britannica

say about this spot?

From the Black Canyon to the sea the Colorado normally flows through a desert-like basin, to the west of which, in Mexico, is . . . Laguna Salada . . . which is frequently partially flooded . . . by the delta waters of the Colorado.

Every time I’ve seen Laguna Salada, it’s been as dry as a bone. Well, let’s be fair; even back at the end of the nineteenth century, water-holes might suddenly go dry . . .

Of the total length of the Colorado, about 2200 miles, 500 miles or more from the mouth are navigable by light steamers . . .

From here to the Colorado’s mouth is about a hundred miles. A light steamer might still navigate this creek, a toy one pulled by a string.