Imperial (38 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

At first our insurgents vote dovishly against independence; they want a union with the Mexican Liberals against Santa Anna’s dictatorship. But

the weakness of the Mexican Liberals and the necessity of securing aid in the States led the Austin party to abandon their opposition to independence.

In other words, they didn’t mean to; they

had

to! And so in 1844, the year that the wagon route to California begins, the United States and Texas sign the Texas Annexation Treaty. The following year, Texas gets annexed; once more, we offer Mexico five million. Preposterously, Mexico refuses us. In 1846, the Mexican War accordingly begins. It is, like all wars, a just war.

We were sent to provoke a fight,

recalled Ulysses S. Grant,

but it was essential that Mexico should commence it.

The American flag goes up over San Diego, then the Battle of San Gabriel breaks Mexico’s grip on Upper California. In General Sherman’s summation,

California was yet a Mexican province,

although now

held by right of conquest.

Time to clarify that situation. Our numerically inferior but better drilled troops, generalled by Taylor and Scott, therefore set about overcoming Monterey’s sandbagged parapets, the walls of Vera Cruz, the precipices of Cerro Gordo. Grant again:

My pity was aroused by the sight of the Mexican garrison of Monterey marching out of town as prisoners, and no doubt the same feeling was experienced by most of our army who witnessed it.

Escaping the yellow fever, winning Puebla, we enter the Valley of Mexico! If I weren’t so parochial, I’d tell you about the battle of Churubusco. Creeping forward, sheltered by the aqueduct-arches of Mexico City, we recapitulate the feat of Cortés.

In 1848, our defeated enemy signs the Treaty of Guadelupe-Hidalgo. Instantly,

59

half of Mexico becomes American, for which we magnanimously pay fifteen million. The new international line runs right through the area which I call Imperial.

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS.

Chapter 21

RANCH SIZE (1800-1850)

Being of or from the Border can provide unique opportunities.

—James Bradley, ca. 1995

B

ut before it does, let us peep like good realtors at the near-virgin territories around Imperial in their earliest subjection to European subdivision.

Horses are the cheapest thing in California; very fair ones not being worth more than ten dollars apiece . . .

notes Richard Henry Dana, Jr., in 1836.

If you bring the saddle back safe, they care but little what becomes of the horse.

Horses were cheap because properties were vast.

When Cortés’s conquistadors, finding, as human nature inevitably will, less gold than cupidity expected, they compensated their disappointment with huge land grants. In the nineteeeth century, we find, for instance, Hacienda Sánchez-Navarro, which at one point possessed over fifteen million acres—ten times the areas of the Imperial and Mexicali valleys put together. The book from which I snatch this information does not claim that the Sánchez-Navarros owned the largest hacienda in Mexico, only that this is

the estate for which we have the most information.

Who knows what other leviathans darkened the murk of those times?

Meanwhile, out in the pueblos of Mexico, we continue to find the rural people, which is to say the

indios

and

mestizos,

clinging to family subsistence plots. I suspect that for them horses were not cheap. In California, however, any poor man could get his own horses. All he had to do was catch them and tame them.

The missions had been secularized by decree in 1833-34. The

mayordomos

who administered them devoured as many of their acres as possible. It was now, in the senility of Mexican California, that most of the land grants were made.

The mythos of Imperial on both sides of the line is this:

He made a success through his own efforts. His farm has been highly improved.

In the

ejidos

of the Mexicali Valley, and pioneer biographies of Imperial County, a parcel-holder’s home is his castle. Subsistence farming was practiced in recent memory (in Southside, at least), even as I write. This ethos derives from the existence or pretense that most farms or ranchos are, like Los Angeles’s original land grants, smallish and comparably equal.

Accordingly, this book will track the size of Imperial’s farms and ranches. If water is the Marxist “substructure,” then land is the “superstructure” whose history turned American Imperial into gardens of Paradise, on whose border Border Patrolman Dan Murray had been stationed; I can hear him saying: They’ll pop their heads up in a minute.

An official of the district agrarian tribunal in Mexicali said to me: Before, the land parcels were huge. People would often say:

As far as you can see, that’s mine.

There was a high proportion of large landowners. Since it was so sparsely populated, that was the bait.

By

before

he meant

before the Revolution.

As for the huge land parcels he referred to, to the extent that they existed in half-unsurveyed Mexican Imperial, they remained as inchoate as Tijuana, as old Spanish Imperial itself—at least until the Chandler Syndicate came from Northside. That story has not yet begun.

But not all Mexican California was the Valley of Death! Along the Pacific coast, livestock could graze without overmuch irrigation. And so that region, human nature being what it is, became a heaven of large land grants. I am informed that ranchos were legally required to be no more than eleven square leagues, which is to say forty-nine thousand acres; but some happened to be larger—as shown, for instance, by Rancho Cañón Santa Ana’s thirteen thousand acres in present-day Chino, San Bernardino County. In 1850, most of what is now Orange County belonged to eleven families.

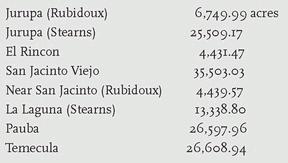

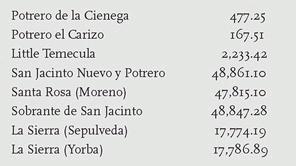

In what would soon be called the Inland Empire, the following grants displayed dizzily varying acreages:

MEXICAN RANCHOS IN RIVERSIDE COUNTY AREA

As for Imperial itself, I repeat: Since irrigation had scarcely begun, most of it remained blank. (To a property owner, Indians are walking blanknesses.)

There are no 1850 Sites to Visit in Imperial County.

Chapter 22

MEXICO (1821-1911)

They did not recognize themselves as the only real hope for the future in a world caught in the grip of horrible ghosts of the past . . .

—Arkadi and Boris Strugatski, 1964

W

ith his squat, dark features and a stature of not much more than five feet, Benito Juárez resembles, as well he should, the indigenous ones who people the images of Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. This first Indian to become President of Mexico looks out at us from an engraving, stiff and straight, with his right hand on the open book on his desk (could it be a Bible?). Harsh, brave, enduring much, let him be our representative of poor Mexico herself, who, amputated at the waist by the Americans; invaded by the Spaniards in 1829 because they could not yet forgive the independence she had achieved in 1821; invaded again by France in 1838 in the so-called Pastry War; menaced in 1861 by England, Spain and France, so that she could be occupied in 1864 by that tall, pallid, bearded, gorgeously uniformed Hapsburg puppet of the French, Maximilian, a man who drew on an empty treasury in hopes of beautifying an ungrateful capital, and succeeded in syncretizing nothing but the music

60

—Juárez, once he finally won the guerrilla war, had him shot—meanwhile tormented herself with uprisings and civil wars. In his short black coat and his handmade white shirt (courtesy of his wife) he gazes at us with alert caution. His principal achievement, like Mexico’s, is that he survived.

After the nation’s humiliating defeat by the North Americans,

I read,

Juárez restored his nation’s dignity and esteem.

But at midcentury the Caste War breaks out in Yucatán. Three years later a third of the Maya have been wiped out. Then here comes the Liberal uprising of Ayutla that kills four thousand; and, as Kurt Vonnegut would say,

so it goes.

In 1856, the Ley Lerdo, second of the famous Reform Laws, required the Church to sell her remaining lands. Lumped into this same unprogressive category of corporate holdings were many of the shared fields of the pueblos. It is saddening, although not surprising, that Juárez, who came to power in 1867, thought facilitating centralism and capitalism to be more urgent than the preservation of communal autonomy.

61

In the short run he might have been correct: He intended to raise agricultural production, and haciendas could certainly do that.

In the long run,

writes Mark Wasserman,

the Reform served to concentrate landholding even more than previously.

One reason was that as the haciendas aimed at commercial crop production with modern methods, they needed more water. That water could be conveniently obtained by annexing pueblo lands.

Benito Juárez died in office in 1872. Five years later, the first presidential term of Porfirio Díaz began.

More gorgeously accoutered than Juárez in a uniform with epaulettes, medals and braids, he gazes out at us handsomely and remotely. His white moustache curves down. This proud old soldier-dictator made better luck for himself than his predecessor ever could have, for by now, thanks to his suppression of various internal instabilities, the foreigners who had bled away so much Mexican blood and pride had begun to appreciate their victim’s investment possibilities. Under Díaz, the economy grew accordingly. He built railroads to get Mexico’s silver ore, coffee beans and suchlike commodities to market in a cheap and timely fashion. Much of that market was in Northside, and the railroad lines were at first owned by Americans. So were ever so many other things, for Díaz’s Mexico was a wonderland of foreign concessions.

Accordingly, here is an authorized Northsider version of the tale:

Then came the long, firm rule of Porfirio Diaz, who first broke up the organizations of bandits that infested the country, and then sought to raise Mexico from the state of discredit and disorganization into which it had fallen. Suspicion and jealousy of the foreigner is disappearing, and habits of industry are displacing the indolence and lawlessness that were once universally prevalent.

Thus my 1910

Britannica.

It was under the regime of Porfirio Díaz that Imperial finally announced:

WATER IS HERE

.

His Law of Colonization (1883) compensated the private sector for surveying vacant government lands. In Mexican Imperial, the new settlements this measure aimed to establish were facilitated by the higher wages of Northside, which forced Southside employers near the line to raise their own wages somewhat—a phenomenon that continues as I write. And so more Mexican migrant workers began coming to the United States. Other Mexicans passed through American Imperial in their eagerness to gamble in the California Gold Rush.

Seven thousand five hundred and eighty-three people lived in the entirety of Baja California Norte in 1900. Meanwhile a total of 13,607,259 people got counted in Mexico,

of which less than one-fifth (19%) were classed as whites

(the same proportion as in the census of 1810),

38% as Indians, and 43% as mixed bloods.

Out of less than fifty-eight thousand foreigners, there were

a few Chinese and Filipinos,

the Japanese exerting a more powerful presence.

And so Mexican Imperial remained “undeveloped.” Elsewhere in Mexico, many government lands were vacant only of clear title; they belonged to the pueblos. No matter. The haciendas bought them up—and not from the pueblos, but from the government.