Imperial (45 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

A certain philosopher asserts that

a space is something that has been made room for, something that is cleared and free, namely within a boundary,

and I’ll leave out his Greek derivation.

A boundary is not that at which something stops, but, as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something

begins its presencing. End of citation. Is the glass half full or half empty? When we gaze into a prison, do we see a place where freedom stops or a place at which confinement with all its horrors begins its presencing?

“AS THIS IS NEARLY ALL DESERT WE HAVE NOT INCLUDED IT”

These semi-gruesome speculations remain academic to Imperial in 1893, when the business directory’s map of Riverside County ends not far beyond Beaumont and Banning, with this legend on the rightward edge:

The County extends Easterly to Colorado River, 125 miles

. Why should Riverside Imperial be deleted?

Our handsome map shows clearly every part of the county except the eastern, and as this is nearly all desert we have not included it, as it would make the map a bad shape for handling.

We do at least find mention of Indio in the directory.

The peculiar situation makes it extremely warm, it being about 200 feet below sea level . . . Fruit ripens here very early.

The place is recommended to consumptives. Two station agents reside there; likewise two section foremen, a coal heaver, two pumpers, a viticulturist, a lady hotel proprietor . . .—in short, less than a page’s worth of inhabitants, in comparison to Riverside City’s eighty. As for Palm Springs, that’s

a small settlement on the Southern Pacific railroad.

Its population is comparable to Indio’s, but they’re mostly farmers and laborers.

Am I making myself clear? Ten years before the cut, a county history advises:

Though large parts of this may certainly be reclaimed by the waters of the Colorado, we are not at present recommending our desert.

Chapter 34

THE DIRECT GAZE OF THE CONFIDENT MAN (1900)

“We have only one standard in the West, Mr. Holmes.”

“And that?”

“What can you do?” came the words as if spoken by cold iron.

—Harold Bell Wright, 1911

A

nd then, right at the turn of the next century, I see W. F. Holt standing in a brimmed bullet-shaped hat, blurrily grinning and clenching his fists beside a railroad track. “W. F. Holt Looks Into the Future with the Direct Gaze of the Confident Man.”

I can’t help believing in people . . . I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life . . . I’ve found that the way to get your money is to give a man a chance to pay you.

Thanks to men like him,

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS.

Chapter 35

ADVERTISEMENT OF SALE (2002)

Prof. David B. Chaplin, formerly principal of the B-street school, . . . resigned

a month ago because he saw an opportunity to make a fortune at Imperial . . .

The professor wanted to get away several weeks before he did, and declares

that thrice the amount of his salary . . . was slipping through his fingers every

day he remained after the opportunity opened for him at Imperial. He says

that there is a veritable boom on the desert . . .

—Imperial Valley Press and Farmer (1903)

PUBLIC NOTICE: ADVERTISEMENT OF SALE

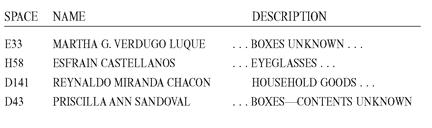

NOTICE HEREBY GIVEN that the undersigned intends to sell the personal property described below to enforce a lien imposed on said property under the California Self-Service Storage Facility Act . . .

And in material advantages they are already well supplied. He sold out at a fancy price.

Chapter 36

IMPERIAL TOWNS (1877-1910)

He saw the country already dotted with the white tent-houses of the settlers . . . He drew a deep breath, and, taking off his sombrero, drank in the scene.

—Harold Bell Wright, 1911

H

olt didn’t do it alone; he was preceded by missionaries of capital. Do you remember how the Jesuit and Franciscan missions crept up Baja California and northwestward through Sonora, then commenced to stipple Alta California itself? I’ve claimed that each of these was a thread of borderline cut to length and wrapped around itself to keep Southside out. The Imperial of W. F. Holt lay mostly within the bounds of Northside; now the islands no longer had to be walled and soldiered; for they housed not authority, which already controlled the paper blankness of the maps, but

money,

or, to be more specific, property development. What else could live in Imperial?

During our passage across it,

writes Pattie in 1830,

we saw not a single bird, nor the track of any quadruped, or in fact any thing that had life, not even a sprig, weed or grass blade, except a single shrubby tree.

Tortured by prickly pear thorns, compelled to moisten their lips with their own urine, Pattie’s expedition staggered across

this very extensive plain, the Sahara of California,

and were saved at the last hour by a stream of snow-water.

In the 1880s, the appropriately named locality of Cactus first appears upon Imperial’s blankness;

71

a decade later, Glamis and Hedges will keep her company there. Next comes Picacho, on which Mexican prospectors have actually been feasting since 1862. Meanwhile, in southwestern parts of Imperial, cattlemen begin to send their stock to gorge on wild grass during the cooler months. In 1893 the engineer Charles Robinson Rockwood, who will bear much responsibility for the disaster that causes the Salton Sea, surveys much of Imperial. In comes our friend George Chaffey, “the father of the Imperial Valley.” In 1900 he and Rockwood sign a contract.

WATER IS HERE

. Rockwood will force him out in 1902; I can’t help believing in people. Between 1900 and 1910 come Ogilby, also known as Ogilvy (twenty-one residents listed in the San Diego County directory for 1901); Andrade, which unlike Ogilby is not quite long, long gone, even though it’s sufficiently out of the way to be more than fifty percent of the time on the wrong side of the All-American Canal; Calexico; Heber; Blue Lake (I mean Silsbee); Mobile; Meloland (the former Gleason Switch); Imperial; Braley, which is now Brawley because Mr. Braley refused to have any town in that godforsaken place named after him; Holtville, which would have stayed Holton except that the Postal Service objected to the similarity to Colton; Cabarker, which, showing marked ingratitude to Holt’s partner C. A. Barker, we refer to nowadays as El Centro; Imperial Junction, which has gone blank but was not entirely unrelated to Niland (date of birth: 1914); and we shouldn’t neglect dear Westmorland with and without its

e.

In 1963, the Ball Advertising Co. will proclaim Westmorland

one of the state’s top cotton-producing areas.

What might it look like on its incorporation in 1910? Well, well, it was an Imperial town.

The rattler was the most dreaded thing there was little else living here,

there was little else living here,

writes an old Imperialite lady in 1956.

As to humans, a prospector now and then came thro in his way to the hills.

A mid-twentieth-century author who is sour about his own era and correspondingly sentimental about the past assures us that the years 1890 to 1915 constituted

a halfway Utopia of civilized development

in southern California. To be specific,

blacksmiths’ shops were community centers for men. While the men baled hay together they sang together. In summer when the apricots were ripe the young people worked cheerfully and flirted in the orchards . . .

If this vision ever possessed any more reality than its analogue in the brightly exhortatory posters of Maoists, I cannot believe that it survived the scorching emptiness of, for instance, Cameron Lake in 1896, which was a longish tract of milk with green-fogged dirt around it, on the far side a low and indistinct coast of shrubs or trees, no scale anywhere, everything lost—the result of improper fixing by the dead photographer, but nonetheless poetically true, for Cameron Lake, like so many Imperial towns, has become itself quite well and sufficiently lost. In those days the dichotomy between Imperial and its antithesis in greater southern California was not only less marked, everything being less “developed,” but it also had less to do with what we now define as rural

versus

urban than with the ancient delineation of aridity

versus

lushness, which meant, from a homesteader’s point of view, near-impossibility

versus

some kind of guarantee, for which one paid accordingly to the land development office.

Ever since the middle of that century, railroads had been crawling out of Los Angeles, northwest and west, south and southeast, with a long eastward arm jiggling through El Monte, Pomona, Cucamonga, Colton, Riverside. Soon the Bee-Line Railroad would connect San Diego Bay right over the Colorado River and across Sonora, Mexico, all the way to Calabazas in the Arizona Territory. In 1887, fifteen hundred Chinese were working on the railroad from Oceanside to Santa Ana. When we finished kicking the Chinese in the teeth, it would be time for Colis P. Huntington to solicit more Mexican workers; one way or another, the railroads grew every which way; and I imagine that from the point of view of Capital, as reified by the direct gaze of the confident man, all this was already meant to be one entity, so that Cameron Lake could look forward to matrimony with San Diego County’s two-storey houses with their second-storey porches looking out over picket-fences at mountains, mineral springs, orchards and wild deer. But who wants to kiss a bride whose lips are dry and whose mouth is a travertine cave packed with sand?

“ Moisture Means Millions .”

Emblematic, therefore, was Blythe, whose eponymous millionaire founder, you will remember, had been irrigating his acres there ever since 1877. The irrigators of the Imperial Valley would take note of Blythe.

WIDE-AWAKE WHITE MEN

Across the county line, Indian Wells and Woodspur already stake their claim to the Cahuilla Valley; they’ll become Indio and Coachella. (In 1877, twelve hundred Chinese, five hundred Indians and a hundred-odd individuals described as “white trash” were working on the railroad thereabouts; we need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.) The first homesteader files on his hundred and sixty acres there in 1885. In 1887, on the very edge of the entity known as Imperial, lands of old Spanish settlements on what was then called San Gorgonio get bought up by a syndicate which changes the name to Beaumont. And not far east of Beaumont we find a Big Palm Spring, which has been here since 1871. It now changes its name to Agua Caliente, a far from unique appellation; the de Anza Expedition had applied it to a Cucapah town just east of Imperial. In the new Agua Caliente, which in my time (1887) will go on the real estate market as Palm Springs,

72

you rent your adobe house from an Indian family, who move into a brush shantey near by, on short notice—charging you, for their vacant domicile, in a ratio which is truly “childlike and bland.”

How tragic, this guidebook continues, that some “wide-awake white man” can’t get ahold of Agua Caliente! Well, well; that just may happen.

In 1894 somebody strikes an artesian flow at Mecca. Farming begins. Thermal has been there for an unspecified number of years, hiding beneath the unpromisingname of Kokell. Kenworthy has appeared by 1900. We next find, in this order, Marshall Cove and Arabia. Out of order, we get Salton and Dry Camp.