Imperial (9 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Officer Murray said that one time a woman in Calexico had telephoned an agent for help. It came out that she’d hired a coyote to get her son as far as Calexico, and then her money ran out, so the coyote’s

pollistas

were holding the kid in a room in that hotel and would not let him go. The Border Patrol rescued and deported him. So the woman lost her money, and I don’t know what the coyote did to her.

THE CARE AND FEEDING OF CHICKENS

One additional consequence of the cash-on-delivery system was that if the package got lost in transit, the shipper saw no reason to inform the recipient, who now would not be liable for payment. To my mind, this was the most evil aspect of the trade. A

pollo

trusted himself to a coyote, and either arrived in due course or else disappeared forever, in which case the ones who loved him never learned his doom.

If a people dies on a coyote, said Juan the cokehead, coyote’s not gonna tell the other people that they died.

All right. But let’s say your sister up in the San Fernando Valley paid the coyote half to bring you, and then you died. What would happen then?

Actually, the cokehead said, the people that come from south Mexico, at the beginning the coyote gets in touch with their family by phone. So then they never get the coyote’s number and address. And if the

pollo

dies, the coyote just never call no more. So they never find out. The people that live here in Mexicali, they’re more safe. Because they know who’s the coyote in this town. But still it’s not that safe. Sometimes, the

pollos

get out in that hot, hot desert where they never been before. And they’ll be waitin’ there for the ride that doesn’t show up.

Border Patrol agents possessed any number of gruesome stories on this subject. Gloria Chavez, for instance, told of twenty-two people who were found in a boxcar in the heat of south Texas after sixteen hours. A sharp-eyed agent saw a feebly reaching hand. All of them were saved.

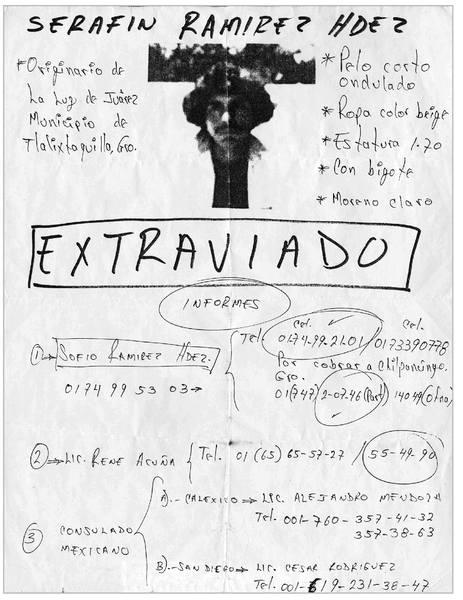

THE UNKNOWN END OF SERAFÍN RAMÍREZ HERNÁNDEZ

In the same palm-treed park where Carlos and his “family” prepared and hoped to cross the border, on a hot afternoon two young men were distributing flyers for a

pollo

who’d vanished twenty days ago, in company with twenty-one other hopeful chickens. The chicken-handlers had taken him across the desert to Northside in a 1979 Dodge van which overheated and finally caught fire south of Carrizo Wash. While the two men were telling me this nice story, a Mixteca street musician squeezed her accordion which butterflied so beautifully red and black, and the girl looked at me most mournfully and hopefully—in short, most professionally—while her younger sister held a beggar’s cup in my face, wearing an even more plausible sad expression; and the smallest sister of all crawled in the dirt, drinking from the big water jug which she could barely lift. Who could blame those girls if they wanted to try their luck across the wall in Northside? The two leafleters waved them aside so that I could get the horror down reliably for this book. They feared that perhaps the missing man had been left to broil alive in the coyotes’ van. The Border Patrol had found bodies inside the Dodge, they said—burned bodies.

As the

Calexico Chronicle,

which might or might not have been more accurate, told the same story, there were no corpses in the vehicle. A “concerned citizen,” it said, had turned over an illegal to Border Patrol agents at the Highway 86 checkpoint. The

pollo

led agents to the smoldering van. The agents then caught nine other people who’d straggled to scattered spots between two and five miles south of Highway 78 in that fearful heat. The remaining twelve were not found. Did one or two reach water somewhere? Was the missing man, Serafín Ramírez Hernández, whose blurred head stared out at me from the flyer most distantly, resolutely seeking something beyond and behind me, still alive?

What does he look like? I asked.

Same as me, but more thin, said one man.

He was a good man, said the other. He was the good friend of my brother. Looked same like me, but more tall. Married with three kids.

Why did he go?

To make money.

In the “Imperial Catechism” of 1903 one reads the following questions and answers about doing business there (“Water is King—Here is its Kingdom”):

What kind of labor can be had for ranch work?

The farm labor in the valley is principally foreign; some are Americans, but it is mostly Mexican.

They came to make money a century ago, and they were still coming now.

Do you know his coyote? I asked the two leafleters.

We don’t. Maybe his brother knows him.

Which is more dangerous, to cross alone or with the coyotes?

It’s the same, said one, but the other disagreed and said: If you know the way, it’s more better if you cross by yourself. Because the

polleros

take advantage of you.

They wandered off to put up more flyers. Behind them, on the grass between the white-limed trees, two men squatted and one man lay, each of them guarding a small plastic bag of necessities as he waited for full dark to try America. The sleeping man was on his side, wearing the same plaid shirt and jeans I’d seen on many of the captured

bodies

in that Northside field. With or without coyotes the people would go.

INTERVIEW WITH A COYOTE

And the coyotes themselves, what do they say? Well, as you have heard, they are not so easy to talk to. I did talk to some, mostly on the fly.—Is it dangerous? I kept asking.—Yes, very dangerous, they always answered.

I met two men in Mexicali who confirmed what

pollos

and ex-

pollos

said about them. In a taciturn, colorless way, ever suspicious of exposure, they disclosed some details of their operations, and I have drawn on them here and there. But it was not until Los Angeles that I got to question a coyote for a good twenty minutes, a young one down on his luck; his many close calls with the Border Patrol had scared him into manual labor.

He said that in the days of his glory he had worked only by word of mouth. Friends known to friends could hire him—no one else. He had always been careful (and he had always been small time). He swore that no

pollo

had ever died on his watch. But he did admit that there had been difficulties. For a considerable time he had led groups over Signal Mountain (this was the path on which Carlos had been taken). Once he came down into the Imperial Valley with his chickens and the

pollista

’s van was not there. It was very hot. They waited for two days and two nights without water. How they survived I don’t know. The

pollista

never came. Finally he led them back into Mexico.

He also said that once he and his group had gotten lost, and the Border Patrol had actually helped them, showing them which way to go.

But mainly he feared the Border Patrol.

His answers were a series of lifeless banalities and feeble negations. Had he ever raped any hens in his flock?—No, he replied greyly (what else would he say?). How much had he charged?—Twelve hundred, the same as everybody else.—How many

pollistas

went with him?—Sometimes one, sometimes two, sometimes none.

He was less evasive than dull. Perhaps he had not suffered much; or he might have lacked the aspirations of his

pollos.

But now he was here, and must make a life for himself like them.

I asked him whether he wanted to make good money again.

The coyote looked upon me with the black gaze of an owl on a gate in full daylight, turning his head and blinking. He said he didn’t think that he would try his old career again. Maybe he was only being politic.

Really he was like his chickens—shy, inarticulate, uneducated, hungry. He was no villain, merely a failure. He lurked and crept through life . . .

A BORDER PATROL SUCCESS STORY

Who was winning, the

bodies

or the body-snatchers? The rising price a

pollo

had to pay was one testament to the Border Patrol’s success. And every

pollo

or coyote who ran scared was another.

In Mexicali I met a clean man of thirty-three years whose occupation was to pass out leaflets advertising dental implants. He usually slept in the street, but took a shower every day. He said: I tried to cross the border seven times, and I almost made it at Tecate. The coyotes took me out of Mexico with no money. But the Border Patrol catch me in Chula Vista. It was hard for me to come back. They kept me three days. They let me off in Juárez.

How did they treat you?

They feed you, but they verbally abuse you.

Do they beat you?

No, but sometimes they push you against the wall if you talk back to them.

Will you try again?

No, I don’t wanna try. It’s too hard.

And then there was Rubén, who’d lived in Las Vegas and Sacramento until he’d been caught. Now he was working in a taco stand in Mexicali trying to save up enough money to return to Nogales, where the coyotes charged only five hundred dollars instead of twelve hundred and he might not even need a coyote at all because the border crossings were so much easier; after all, he’d lucked out there before, saying to the officer:

Hey, I’m a citizen, man, but my papers were stolen.

He couldn’t afford a Mexicali coyote now.

Before I started working here, said Dan Murray, I guess I thought our border was like the Berlin Wall. Well, when I saw all the holes and raggedy-ass places, I couldn’t hardly believe it.

It was more like the Berlin Wall each year.

Nowadays, it’s very clean out there, said Gloria Chavez in Chula Vista. Operation Gatekeeper began in 1994. At that time we had seven hundred agents in this sector. Now we have two thousand two hundred and fifty. We’ve established a nationwide database on each person we capture, along with fingerprints. This sector contains sixty-six miles of border, of which forty-four are fenced. There are twenty-four point two miles of secondary fencing. Fencewise, and it’s very sad to say it, before Gatekeeper we had only eight miles. Before Gatekeeper, we were arresting half a million people a year. In 1998 there were only two hundred and forty-eight thousand in detention.

So you’ve cut the number in half, I said. Her statistics reminded me of the numbered sections of rusty landing-mat fence marching up and down the dry hills against which Tijuana pressed and strained.

That’s right, she said. And we’ve cut the number of deaths also. In 1995, eighty-two aliens died in this sector. The main cause of death was homicide. The second cause was accident on the freeway. In 1998 we had only forty-two deaths, the leading cause of which was hypothermia. A hundred and forty-two were rescued. We’re gonna do everything it takes to save those lives.

EPITAPHS IN A NEWSPAPER

I opened up my hometown newspaper and it said: At least 168 people have died during the past 15 months trying to cross illegally into the United States from Mexico over treacherous mountain and desert terrain in eastern California and Arizona, a toll in large part the result of tighter U.S. patrols along the border in the San Diego area. Yet as tragic as these events are, the patrolling policy, known as Operation Gatekeeper, is the correct one.

I wonder what Serafín Ramírez Hernández would have made of that.

Six weeks after his disappearance, I telephoned the Mexican consulate in San Diego in hopes that he had been found.—His brother Sofio he has been in contact with us so many times, the woman sadly said. We also check with our contacts here. He’s not in any hospital or detention center, or . . . The file is still open, and it will remain open until we find something.

How often does this sort of thing happen?

It’s unfortunately very often, she said.

9

Meanwhile, the front page of the

Calexico Chronicle

had proclaimed:

Border Patrol Unveils Public Service Announcements Featuring Widow of Smuggling Victim.

The figurehead of these announcements was to be the twenty-five-year-old spouse of a

pollo

who perished with ten other illegals near El Centro when their coyote or coyotes ran away. Sector Chief Wacker was quoted as saying: I believe that Jackie’s plea is very clear . . . We hope that the message will make everyone fully aware of the smugglers’ priorities and of the dangers involved in entering illegally. —My government had figured out that it could use deaths caused in part by its own policies to make propaganda.

MEMBERS OF OUR LABOR FORCE

Of course Operation Gatekeeper could foil some of those

bodies,

so that Serafín Ramírez Hernández became in truth a dead or missing body; and others were apprehended or discouraged. All the same, even if Murray’s fantasy ever did come true, and the border became another Berlin Wall, it would never completely, much less permanently, contain the amazing boldness and determination of the

pollos

and

solos.

We were no match for them.