Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald (11 page)

Read Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald Online

Authors: Barry Krusch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Ahhhh, you say, now the light bulb is turning on!

Yes, unfortunately for the premise of King’s novel, it turns out that we do not live in North Korea, nor China, nor any imaginary dystopia which would employ a standard so bizarre . . . and so

unjust

.

Instead, we live in the United States of America, where the standard of proof is much higher, and thank G-d for that (if you’re an atheist, thank the Constitution). Equally important, that standard of proof has to be determined by not just

one

person, but

twelve

people,

all

in agreement, gathered together in a group we call a “jury”, who listen to testimony from a jury box. Count the seats:

So, whatever the standard happens to be, we know that it is much, much higher than the unreasonable chance standard, and because of it, the chance of convicting Oswald would be much, much lower, perhaps even approaching . . .

zero

!

“But Barry, how can you say that?”, you say, “didn’t Bugliosi win before a jury on

Showtime

in 1986?”

Yes, indeed; in 1986. But new evidence has come out since then, and the defense is a lot more refined than that presented by Gerry Spence. And who knows how

that

“trial” was controlled, anyway? And how the jurors were selected? And what nondisclosure agreements did they sign? Was it on

Showtime

for a reason?

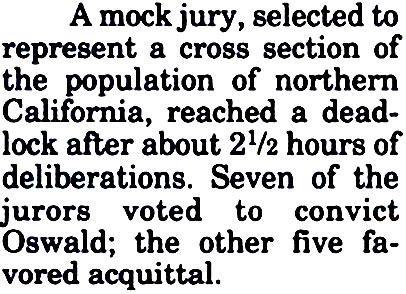

Indeed, another (later) mock trial did not have the same result (“Jury Deadlocks in Oswald Mock Trial,”

ABA Journal

, October, 1992, p. 35):

Note what this article concludes, as I mentioned above: there have to be

twelve

people on the jury, and they

all

must agree. If they don’t

all

agree, that is a

deadlocked

jury, what is sometimes known as a

hung jury

. If the jury can’t reach a decision, then there has to be a new trial, with a new jury, and the cycle will start all over again, if necessary.

And that is the way the justice game is played in the U.S. of A. Love it or leave it. For my part (for what it’s worth), I love it. I hope you do too.

Now that the cobwebs have begun to clear away from our mind, it is time to get serious. We had a lot of fun with aliens and UFOs earlier on, but when the evidence doesn’t fit the conclusion, that hard dose of reality is going to wipe the smile off our faces. And the reality is that the standard of proof required to convict Oswald is a very difficult one to meet.

Let's learn more about it.

While typically thought to be a quintessentially American concept, it turns out that the concern for protecting the rights of the innocent by applying an extremely high standard of proof has an ancient, very rich history, a history by no means confined to the United States.

Maimonides, writing in the 12th century, codified 613 commandments in the Jewish Bible, and wrote the following about Commandment 290 (emphasis supplied):

1

The 290th commandment is the prohibition to carry out punishment on a high probability, even close to certainty . . . .

Do not think this law unjust. The Almighty shut this door and commanded that

no punishment be carried out except where there are witnesses who testify that the matter is established in certainty beyond any doubt . . . it is better and more desirable to free a thousand sinners, than ever to kill one innocent.

Nor was this view by any means confined to Judaism. It is part of what might be considered “natural law.”

According to Professor Sandy Zabell, Professor of Statistics at the University of Chicago, the earliest reference in non-religious legal literature was authored by Justinian:

2

The Divine Trajan stated in a Rescript to Assiduus (sic) Severus: “It is better to permit the crime of a guilty person to go unpunished than to condemn one who is innocent.”

But, though the concept was an ancient one, America did provide a vehicle for formal recognition of this value in the Constitution of the United States of America, specifically, the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, which provide (respectively) in pertinent part as follows:

No person shall be . . . deprived of life, liberty, or property, without

due process

of law . . .

3

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without

due process

of law . . .

4

According to these Amendments, due process is the framework within which the mechanisms of criminal law operate. But what processes are “due?” There is an entire suite of these, and it is in the

definition

of these processes that we find the stipulation of the

means

by which the

innocent shall be protected

, and that means is through the creation of

a high standard of proof

.

Here is the standard:

In criminal law,

innocence is presumed

until guilt has been proven to the factfinder — a jury —

beyond a reasonable doubt

.

Note that the standard specifically refers to

being found guilty

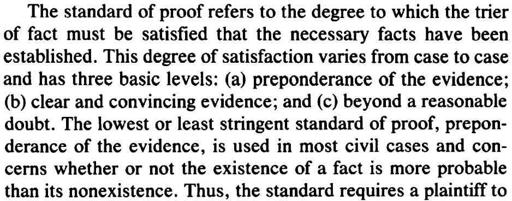

of a crime. In other areas of criminal law, and also throughout civil law (lawsuits between two parties involving negligence, defamation of character, etc.), there are other, lower, standards of proof. Two of these standards are “preponderance of the evidence” and “clear and convincing evidence,” as noted by Dorothy Kagehiro (Kagehiro, 1990, pp. 194-5; paragraph on separate pages combined by author):

But these lower standards are also applied not only in civil law, but also in a different area of criminal law, pretrial detentions, as reported in 2010 in

The Georgetown Law Journal Annual Review Of Criminal Procedure

(footnotes omitted; emphasis supplied):

5

The

Bail Reform Act

allows courts to detain an arrestee pending trial if the government demonstrates by

clear and convincing evidence

after an adversarial hearing that no release conditions will reasonably ensure the safety of the community. In

United States V. Salerno

, the Supreme Court held that pretrial detention of a defendant based solely on the risk of danger to the community does not violate due process. Nor does pretrial detention on the ground of dangerousness constitute “excessive bail” under the Eighth Amendment; the prohibition against excessive bail applies only to cases where it is appropriate to grant bail.

A judicial officer may also detain a defendant if the government proves by a

preponderance of the evidence

that the defendant poses a risk of flight such that no condition or combination of conditions will reasonably assure the defendant’s presence at trial. In assessing risk of flight, courts consider a variety of factors, including the defendant’s ties to the community, past criminal history, and availability of assets. To detain a defendant, a judicial officer must find the defendant to be either a risk of flight or a danger to the community; proof of both is not necessary.

As noted above, these lower standards can be utilized in arrest

before

trial. But to find a person

guilty

of a crime after they have been arrested and

after

a trial, the

reasonable doubt

standard rules. The purpose of the standard from the American perspective was described by Barbara Underwood, Associate Professor of Law at Yale University, writing in the

Yale Law Journal

(emphasis supplied):

6

The first function of the reasonable doubt rule is to reduce the chance of conviction in an individual case, by putting a thumb on the defendant’s side of the scales of justice

. . . . One reason for putting a thumb on the defendant’s side is to compensate for a systematic flaw in the scales. That is, factfinders may favor the prosecution rather than weigh the evidence objectively. . . . In reducing the likelihood of an erroneous conviction, the reasonable doubt rule does not, however, simply restore an accurate balance;

it is also understood to introduce a deliberate imbalance, tilting the scales in favor of the defendant

. It represents “a fundamental value determination of our society that it is far worse to convict an innocent man than to let a guilty man go free.”

Professor Underwood noted that the status of this right was explicitly recognized by the Supreme Court in 1970:

7

The requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal cases was given constitutional status by the Supreme Court in 1970, in the case of

In re Winship

. . .

The Court itself noted in that case that their decision was merely the logical outcome of a line of previous cases (

In Re Winship

, 397 US 358, 361-2; March 31, 1970; emphasis supplied):

The requirement that guilt of a criminal charge be established by proof beyond a reasonable doubt dates at least from our early years as a Nation. . . . Expressions in many opinions of this Court indicate that

it has long been assumed that proof of a criminal charge beyond a reasonable doubt is constitutionally required.

See, for example,

Miles v. United States

, 103 U.S. 304, 312 (1881);

Davis v. United States

, 160 U.S. 469, 488 (1895);

Holt v. United States

, 218 U.S. 245, 253 (1910) . . .

In

Winship

, the Supreme Court quoted noted judge Felix Frankfurter, who reminded us that the burden of proof is not on the

accused

, but on the

government

(

Winship

at 361-2; emphasis supplied):

[i]t is

the duty of the Government

to establish . . . guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. This notion — basic in our law and rightly one of the boasts of a free society — is

a requirement

and a safeguard of due process of law in the historic, procedural content of “due process.”

The Supreme Court linked the

reasonable doubt

standard with the related concept of the

presumption of innocence

, which they referred to as “axiomatic and elementary” (

Winship

at 363 (quoting

Coffin v. United States

)):

The reasonable doubt standard plays a vital role in the American scheme of criminal procedure. It is

a prime instrument for reducing the risk of convictions resting on factual error

. The standard provides

concrete substance for the presumption of innocence —

that bedrock

“axiomatic and elementary”

principle whose “enforcement lies at the foundation of the administration of our criminal law.”

The Supreme Court contrasted the standard of proof for criminal cases to civil litigation. In the litigation of civil cases, the risk to one of the parties is relatively minimal. However, in criminal cases, the risk to the accused is always his

liberty

, and in cases where the death penalty is involved, sometimes his

life

— consequently, a higher standard is called for (

Winship

at 364; quoting

Speiser v. Randall

):

There is always, in litigation, a margin of error, representing error in factfinding, which both parties must take into account. Where one party has at stake an interest of transcending value — as a criminal defendant his liberty — this margin of error is reduced as to him by the process of placing on the other party the burden of . . . persuading the factfinder at the conclusion of the trial of his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Supreme Court went on in the

Winship

opinion to describe the notion of “moral force,” and the importance of the reasonable doubt standard in maintaining the confidence of society by only securing convictions in which there was "utmost certainty" (

Winship

at 364; emphasis supplied):

Moreover, use of the reasonable doubt standard is indispensable to command the respect and confidence of the community in applications of the criminal law.

It is critical that the moral force of the criminal law not be diluted by a standard of proof that leaves people in doubt whether innocent men are being condemned

. It is also important in our free society that every individual going about his ordinary affairs have confidence that his government cannot adjudge him guilty of a criminal offense without convincing a proper factfinder of his guilt with

utmost certainty

.

“Utmost certainty”: sound like a high standard to you? It does to me!

The Supreme Court finally concluded with this ringing and completely unambiguous proclamation (

Winship

at 364; emphasis supplied):

Lest there remain any doubt about the constitutional stature of the reasonable doubt standard, we explicitly hold that the Due Process Clause protects the accused against conviction except upon

proof beyond a reasonable doubt of every fact necessary

to constitute the crime with which he is charged.

With the reasonable doubt standard established as axiomatic in American jurisprudence — that convictions cannot be secured without the

utmost certainty

— we can therefore use it to create a deductive argument that demonstrates why the presumed innocence of Lee Harvey Oswald must always so remain.

Because the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court has given us the inviolable standard of

reasonable doubt

which can — and indeed,

must

— be used for the purpose of legal analysis, we can see instantly that the possibility or impossibility of the conclusion of a legal case can be determined

deductively

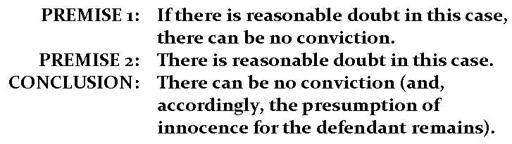

. Consider the following syllogism derived from that standard:

The beauty of deductive logic is that it is absolutely certain: it removes all doubt (from the legal perspective) regarding the presumption of innocence of the accused. This argument, because it is deductively structured, proves that it is impossible for there to be a conviction in any case brought forth by the prosecution where the above two premises are true!

Now, we have seen that the

truth of Premise 1 is conclusively established simply by virtue of our residing under the Constitution of the United States

as interpreted by the Supreme Court in

In re Winship

. This premise is stipulated as true simply by virtue of its legal status.

Accordingly,

all we need to do in the Kennedy/Oswald case to demonstrate that conviction for Oswald is impossible is establish the truth of Premise 2

: that, regarding the case against Lee Harvey Oswald, there is reasonable doubt. If we establish that truth, then we have deductively demonstrated the truth of the conclusion, that there can be no conviction in this case, and, accordingly, the presumption of innocence for the defendant will remain.

To further proceed logically, we must first define a “case,” which we will do as follows:

A “case” consists of a set of premises (to be referred to hereinafter as

propositions

), which, if true, would deductively prove a conclusion, each proposition comprised of a series of necessary subpropositions (to be referred to as

elements

), those elements to be justified beyond a reasonable doubt (or not) by an analysis of

all

the evidence supporting (or contradicting) them.

So, if we had a case whose charge was first-degree murder, a proposition of the case might be “

John Defendant fired a gun proximate to the temporal and spatial location of Jane Victim.

” Then, this proposition could be

further

subdivided into subsidiary facts supporting the proposition. In this regard, it is critically important to distinguish between the subsidiary facts

necessary

to establish guilt — the subpropositions which going forward we will refer to as

elements

— and facts which

may or may not

indicate guilt.

Let’s use our murder case as an example: if the contention is that

the victim was murdered in the city of Dallas

, then the prosecutor must provide

comprehensive

,

credible,

sufficient

, and

consistent

evidence that the person accused of the murder was actually in the city of

Dallas

at the time. If the defense can present evidence that the person accused was located in

Los Angeles

at the time of the murder (i.e., evidence

inconsistent

with the conclusion), then obviously reasonable doubt is thrown on that proposition, by virtue of outright refutation.

So, a

necessary

subsidiary fact (i.e. subproposition or

element

) for this murder case would be

John Defendant was located in the city of Dallas at the time of the murder

. (Of course, this could be refined further, that is to say, in the real world we would make sure that the murderer was located close enough and in the right position to commit the murder, and determine the precision of the necessary elements as needed.) We could also formulate subsidiary facts that are

not

necessary, for example, that

John Defendant had a prior criminal conviction

. This statement is

not

necessary because if the person accused of the crime had no prior criminal conviction, he or she still could have committed the murder. In this case, the subsidiary fact might indicate a

tendency

to commit the crime, but it is not

required

to establish guilt.

Once we know that a case can be divided into

propositions

, which can then be further subdivided into

necessary

subsidiary facts known as “elements”, we can sum up the foregoing analysis into the following statements:

- The case for conviction regarding a particular charge rests on propositions that, taken together, can deductively establish the truth of the charge (i.e., the conclusion).

- The validity of each proposition rests on necessary factual elements E1 through E

n

. - Because

each

of these elements is

necessary

to establish the truth of the proposition, the proposition can be considered functionally disproven when there is reasonable doubt for

even one

of these elements. - For each element, there is a set of

evidentiary data

, which taken as a whole may create no reasonable doubt (or varying degrees of reasonable doubt) regarding the veracity of that element. - Reasonable doubt can be created for one of the necessary elements if the evidentiary data for that element (taken as a whole) is either not

comprehensive

, not

credible

, not

sufficient

, not

consistent

, or any combination thereof,

to

the extent necessary

to create reasonable doubt. - Consequently, if the evidentiary data for an element (taken together) falls into one or more of the foregoing categories in Paragraph E, reasonable doubt will be created for that element, and the proposition will be functionally disproven.

So, here, in a nutshell, we have the framework for establishing the guilt or maintaining the presumption of innocence of Lee Harvey Oswald:

- First, we must determine the

propositions

. - Then, for each proposition we must determine the factual

elements

underlying that proposition. - Next, for each element, we must establish the total set of evidentiary

data

. - Next, we need to

evaluate

the total set of evidentiary data, and analyze the extent to which the data, taken as a whole, tends to confirm or disconfirm each element, thereby decreasing or increasing reasonable doubt regarding that element. - Because these are

necessary

elements, if our determination shows that there is reasonable doubt for

even one

of these elements, then the proposition to be supported by that element is functionally disproven and, the case shown not proven beyond a reasonable doubt, the presumption of innocence shall remain.

The above statements, because they are derived from the law of the United States, and the laws of logic, are the basic foundation underlying all that follows.

However, as ironclad as these statements might seem, there is actually some “wiggle room” from the deductive perspective: what doubt is

reasonable

? Normally, what constitutes reasonable doubt is determined by a juror subject to

instructions

from a judge on how to define the term. Unfortunately, these instructions generally lack that all-important helpful quality we seek to uncover in a well-formed judicial directive. Consider the following example from a prominent federal pattern jury instruction treatise:

1

A reasonable doubt is a doubt based upon reason and common sense — the kind of doubt that would make a reasonable person hesitate to act. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt must, therefore, be proof of such a convincing character that a reasonable person would not hesitate to rely and act upon it in the most important of his or her own affairs.

Does that settle it for you? Probably not, since this “instruction” is of the prototypical clear-as-mud variety. But it is all too typical of the typical “reasonable doubt” instruction. As Erik Lillquist, Associate Professor of Law at Seton Hall University School of Law noted,

2

These instructions appear to do little to educate the jurors in what is meant by proof beyond a reasonable doubt. They certainly do not quantify how much proof is needed to convict a defendant. But what is most remarkable is how vague and opaque they are. These instructions used in the federal system talk about hesitating to act in an important matter. What does that mean? State instructions are no better. They talk about proof beyond a reasonable doubt as “an abiding certainty” or what occurs after a “careful and honest review” of the evidence. What is a juror supposed to draw from these statements?

That’s a good question. When faced with this problem, what is a good juror supposed to do?

From our perspective, as either potential jurors ourselves or as potential future defendants in front of these jurors, we must realize that because these instructions are vague, they are basically empty vessels into which any thought, whether nonsensical or well-formed, can be poured.

And, in the legal world, this is not a good thing. In fact, elsewhere in the legal world, laws in general can be struck down for being too ambiguous, per the

void for vagueness doctrine

, as Mary Vales told us in the

Seventh Circuit Review

(Vales, p. 251):

From this we learn the following global lesson: specificity, good — vagueness, bad.

How are we to know a statute or a reasonable doubt instruction are vague? With a standard we can call the “guess” standard: if you have to

guess

what it means, it’s

vague

. So, if a reasonable doubt instruction is vague, you will be guessing. When you are guessing, you have no true guidance. And the impact of a reasonable doubt instruction that provides no true guidance should be clear: in a country which tells its children to expect “liberty and justice for all,” and whose most primary document talks of “inalienable rights,” how can the right to a

fair

trial be subject to a term that even a professor of law does not understand!?

With essentially no content, a vague reasonable doubt standard functions as a ruler that can be inappropriately (and silently) expanded or contracted from case to case, and how can a standard that can be inappropriately

rigorous

in one case and inappropriately

lenient

in another provide any standard at all, and without any standard at all, how could there be any protection from an incompetent and/or immoral government absent the standard that could provide that protection, and if there was no protection from an incompetent and/or immoral government, how could there be any

preservation

of the rights we formerly saw as “inalienable”?

Ponder this: if a

professor of law

is confused, how confused would be the

average citizen

, with absolutely no background in the meaning of the term, or in any other areas of legal practice that would enable meaning to be determined?

If you are guessing that empirical studies would show confusion across the United States in this regard on the part of jurors, you’re right. As Dorothy Kagehiro wrote in 1990,

3