Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald (44 page)

Read Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald Online

Authors: Barry Krusch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

BOOK: Impossible: The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald

12.78Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

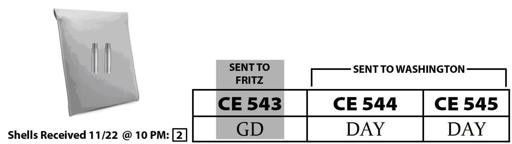

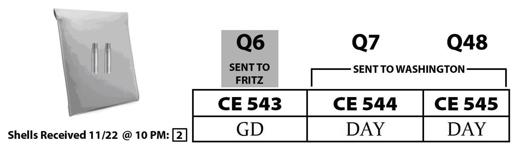

With this revised version of our model, it should now be no problem to answer the question, “in terms of Q numbers, which shells delivered at 10 PM were to be sent to

Washington

?” And, since the model above says that

Q7

=

CE 544

and

Q48 = CE 545

, we have our answer:

The shells sent to Washington — CE

544

and CE

545

— should respectively have been identified (per the 11/23/63 FBI Evidence Received letter) as

Q7

and

Q48

.

But your memory should be telling you a different story, and when we take a second look at the 11/23/63 FBI Evidence Received letter, we are absolutely astonished to verify that in fact this was

not

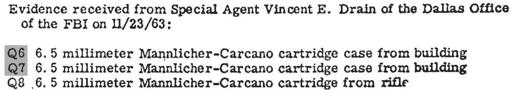

the case (CE 2003, p. 132: 24 H 262):

56

Instead of “Q7” and “Q48,” we see instead “Q6” and “Q7.” Oops!

At first, one might think there was a typographical error by the agents in Washington (even though the sequential nature of the numbers [6 to 7 to 8] would belie that possibility), but, in fact, the highest “Q” number listed in that first receipt of evidence by the FBI was

Q15

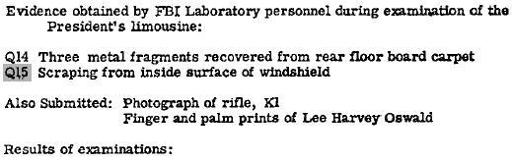

(CE 2003, p. 132: 24 H 262):

57

,

and therefore on that day (November 23), from the FBI’s perspective,

Q48 did not exist at all, and therefore could not possibly have been sent to Washington

!

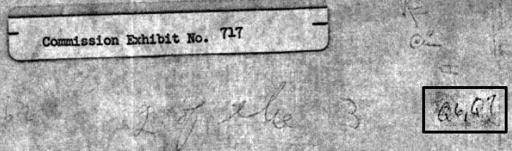

Further verification that the FBI correctly reported the receipt of “Q” numbers Q6 and Q7 is provided by CE 717, the envelope used to transmit the evidence to the FBI: note on the right-hand side the “Q” numbers “

Q6

,

Q7

” (CE 717: 17 H 501):

58

Ouch!

This is what we call a major, major, MAJOR problem for the Fritz story. Here’s why: when we view the model of Day’s testimony, we see that

one, and only one shell

, should have been in Fritz’ drawer, and that shell would have been

CE 543

:

Remember, there are only

three

shells according to the official story, and if CE

544

and

545

have been sent to Washington, the only one left that could be conceivably found in Fritz’ desk drawer

has to have been

CE

543

.

Now let’s look at the Model with the “Q” numbers referenced again (to better able you to see the problem, I will highlight the area on which you should focus):

Note that as we saw earlier, CE

543

is identified as “

Q6

,” and surprise of surprises, the FBI has told us in more than one way (the property inventory record as well as the notations on CE 717) that shell

Q6

(along with Q7) was actually in . . .

Washington

!

And so now we have direct from the FBI itself

absolutely positive

confirmation that the story that Fritz is telling

cannot possibly

be true:

CE 543, a/k/a Q6, could not possibly have been in Fritz’ drawer in

Dallas, Texas

when CE 2003 (the 11/23/63 FBI Evidence receipt) and CE 717 (the transmittal envelope)

prove

it was in

Washington, DC

!

Besides conclusively destroying the story told by Fritz, this testimony by Day coupled with the evidentiary record also destroys the legitimacy of the marks supposedly representing the actual chain of custody.

This is because we know that the shells that were sent to DC according to the FBI evidence receipt and the transmittal envelope — CE

543

[

Q6

] and CE

544

[

Q7

] — had

contrary

marks, one by “GD,” the other by “Day,” when in fact according to the official story as told on April 22 by Day, both should have had the

same

mark, “Day” (Day marked only the shells that were to be sent to Washington, as you will remember, but

Q6

, which

was

in Washington, did

not

have

Day’s

mark, it had “

GD

”

s

!)

This would indicate that at least one shell was sent to DC without the necessary mark required to establish a chain of custody (again, according to the story, because it was sent to

Washington

,

Q6

should have had the mark “

Day

” and not “

GD

”), and therefore Q6

had to have

been surreptitiously introduced into the evidentiary mix!

Furthermore, if in fact there

was

a shell in the desk drawer of Fritz, that would be an extra “Q” number, since the others had been accounted for, and so we can be absolutely sure that that bullet was

not

fired from the rifle owned by Lee Harvey Oswald, since the evidence shows that, at maximum, only

three

bullets were fired in that rifle, and if there

was

an extra bullet, then it was not fired in that rifle on that day, as its marks would indicate, but rather, was

planted

there!

Wow.

This, folks, we can term with no fear of contradiction, is an evidentiary

debacle

.

Needless to say, if this story with its multiplicity of continuity errors were left to stand on its own, the credibility of the Warren Commission could have easily been destroyed with the application of a small dose of elementary deductive logic. However, it appears that some sharp-eyed attorneys in Washington noted that this story would essentially destroy The Case Against Lee Harvey Oswald, so it seems they decided to dispatch a Hollywood script doctor to do reconstructive surgery on the narrative.

When the old story fails, it’s time to roll out a new one! And now, consequently, we are about to see a completely different version of events designed to rehabilitate the prior analysis.

Unfortunately for them, the story-masters were only digging themselves into an ever greater ditch, a ditch that the wise Kennedy assassination student would be careful to examine closely. As Bugliosi noted (

Reclaiming History

, pp. 899-900):

accurate memories of an event or statement tend to fade with time. So

how do we deal with the many Warren Commission witnesses . . . whose memory supposedly got better with time?

Assuming their first statement was intended to be a complete one, and there is no question that the witnesses said what they are reported to have said,

we must, almost by definition, reject

sensational

additions to their original story

.

Are these “additions” by witnesses in the Kennedy case always flat-out lies on their part? In many cases, yes, just as some of their original statements are often completely fabricated

in the hope of getting five minutes of fame or attention. But many times, witnesses are not knowingly telling a falsehood. As time goes by, they naturally forget some of what they saw or heard, and these new voids in their memory are frequently filled in with details derived from the power of suggestion or their own imagination, or from knowledge of later events that make the details more likely or even inevitable, or from the recollections of others that witnesses unconsciously embrace as their own — that is, the witness ends up saying he saw something that he himself never saw. . . .

Other books

Return to Paradise (Torres Family Saga) by Henke, Shirl

Nine Years Gone by Chris Culver

First Team by Larry Bond, Jim Defelice

Shifters, Inc. The Bear Who Loved Me (A BBW paranormal romance) by St. Clair, Georgette

The manitou by Graham Masterton

Love Finds You in Tombstone, Arizona by Miralee Ferrell

A Portal to Leya by Elizabeth Brown

El 18 Brumario de Luis Bonaparte by Karl Marx

Battle Earth X by Nick S. Thomas

The Wielder: Sworn Vengeance (The Wielder Series) by Gosnell, David