In Amazonia

Authors: Hugh Raffles

IN AMAZONIA

IN AMAZONIA

A

N

ATURAL

H

ISTORY

HUGH RAFFLES

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

COPYRIGHT

© 2002

BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaton Data

Raffles, Hugh, DATE

In Amazonia : a natural history / Hugh Raffles.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-04884-3 (alk. paper) â ISBN 0-691-04885-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. EthnologyâBrazilâIgarapé Guariba. 2. EthnologyâAmazon River Valley. 3. Indigenous peoplesâEcologyâBrazilâIgarapé Guariba. 4. Indigenous peoplesâEcologyâAmazon River Region. 5. Estuarine ecologyâBrazilâIgarapé Guariba. 6. Estuarine ecologyâAmazon River Region. 7. Natural historyâBrazilâIgarapé Guariba. 8. Natural historyâAmazon River Region. 9. Igarapé Guariba (Brazil)âHistory. 10. Amazon River RegionâHistory. 11. Igarapé Guariba (Brazil)âSocial life and customs. 12. Amazon River RegionâSocial life and customs. I. Title.

GN564.B6 R34Â Â Â Â 2002

306â².09811âdc21Â Â Â Â Â Â 2002016909

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon.

Printed on acid-free paper. â

Printed in the United States of America

10Â Â 9Â Â 8Â Â 7Â Â 6Â Â 5Â Â 4Â Â 3Â Â 2Â Â 1

FOR SHARON

Pará, December 15, 1928. Mouth of the Amazon.

A young woman who was on our boat, coming from Manaus, went into town with us this morning. When she came upon the Grand Park (which is undeniably nicely planted) she emitted an easy sigh.

âAh, at last, nature,' she said. Yet she was coming from the jungle.

â

HENRI MICHAUX

,

Ecuador: A Travel Journal

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people have read and commented on either single chapters or larger portions of a manuscript that has been in progress for several years; others have made more informal but no less valued contributions. My appreciation runs deep to allâincluding those whose names have somehow escaped this list: Arun Agrawal, Noriko Aso, Iain Boal, Bruce Braun, Graham Burnett, Jim Clifford, Steve Connell, Bill Denevan, Amity Doolittle, Kate Dudley, Carla Freccero, Jody Greene, Carol Greenhouse, Jimmy Grogan, Donna Haraway, Gill Hart, Julie Harvey, Emily Harwell, Amelie Hastie, Cori Hayden, Gail Hershatter, David Hoy, Jake Kosek, Jean Lave, Celia Lowe, Joe McCann, Doreen Massey, Bill Maurer, Ben Orlove, Miguel Pinedo-Vásquez, Anna Roosevelt, Vasant Saberwal, Suzana Sawyer, Candace Slater, Janet Sturgeon, Neferti Tadiar, Liana Vardi, Michael Watts, Antoinette WinklerPrins, Karen Tei Yamashita, and Dan Zarin. In addition, Don Brenneis, Susan Harding, Susanna Hecht, Dan Linger, Christine Padoch, Nancy Peluso, Michael Reynolds, Jim Scott, K. Sivaramakrishnan, Kristiina Vogt, Eric Worby, Heinzpeter Znoj, and an anonymous reviewer from the Press have made major contributions by reading and responding to one or another version of the entire work. In this regard, I owe particular thanks to David Cleary, who twice provided exceptionally detailed, insightful, and generous readings that considerably advanced the project. I am also more than normally indebted to Don Moore, whose sustained commentary has pulled both me and this book further into Pacific Time than would otherwise have been possible. The book has benefited greatly from the attention of two outstanding copy editorsâMaria E. DenBoer and Annie Moser Grayâand from the production skills of Brigitte Pelner and Sarah Green. My thanks also to Lys Ann Shore for preparing the index. Mary Murrell has been everything I hoped for in an editor and more: smart, sensitive, imaginativeâand an inimitable lunch companion!

Individual chapters have been presented at seminars and conferences at Irvine, Santa Cruz, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., the University of Delhi, the University of London, and Yale, and I thank audiences and commentators at these events, particularly Amita Baviskar, Teresa Caldeira, Fred Damon, Rebecca Hardin, GÃsli Palsson, and Adriana Petryna. In London, I remain grateful to James Dunkerley, Stephen Nugent,

and the late Michael Eden for providing a home at the Institute of Latin American Studies, enabling my return to academia and departure for Brazil.

In the United States, I have had the great fortune to work in remarkable institutional settings on both coasts. At Yale, Jim Scott, Kay Mansfield, and the Program in Agrarian Studies welcomed me to what became a formative location. As for Santa Cruz: this book would have been very different and, I am certain, far poorer, had it been written anywhere else. I have learned from all my colleagues, and working at close quarters in particular with Don Brenneis, Jackie Brown, Nancy Chen, Susan Harding, Dan Linger, Ravi Rajan, Lisa Rofel, and Anna Tsing has been equal parts humbling and inspiring.

In Brazil, I am indebted to Jaime Rabelo and Marcirene Machado, Fernando Rabelo and Lúcia, Moacir José Santana, Mary Helena and Fernando Allegretti, Hélio Pennafort, Waldiclei Pereira Ramos, Waldir Pereira, the staff at the SEPLAN library, the Museu Histórico do Amapá, the public library in Macapá, and the Archivo Público in Belém, to Trish Shanley, Célia Maracajá, Toby McGrath, Harry Knowles, and to Dora, Lene, and Walmir, who always found room for my

rede

. I am also grateful to Joe McCann for the memorable visit to the Arapiuns basin that is recorded in

Chapter 2

, and to Michael Reynolds for his friendship on that and other journeys. Above all, though, I owe a permanent debt of gratitude for the extraordinary generosity, kindness, patience, and humor of those I name only by pseudonym: the residents of Igarapé Guariba, Rio Preto, Fazendinha, Macapá, and elsewhere in Amazonia, whose lives animate the pages of

Chapters 2

,

3

,

6

, and

7

.

The research on which this book is based was funded by the Joint Council of Latin American and Caribbean Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies with funds provided by the Ford Foundation; the National Science Foundation; the Program in Agrarian Studies at Yale University; the Yale Center for International and Area Studies; the Yale Tropical Resources Institute; and by faculty research funds granted by the University of California, Santa Cruz. I was able to complete the writing thanks to the award of a University of California President's Research Fellowship in the Humanities and an S.V. Ciriacy-Wantrup Fellowship in Natural Resource Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. I am grateful to Michael Watts for acting as my faculty mentor at Berkeley and to all the above institutions for their generous support.

In addition to the people who figure in its pages, I have written this book for my family in Britain and Ireland, especially for my parents. I dedicate it to Sharon Simpson, lifelong best friend, partner-in-crime. So many years sharing our dreams, anxieties, and passions. Always talking, always thinking, never stopping! So many distances traveled. And always together, even when apart. In every respect, this book is the outcome of our two lives entwined.

IN AMAZONIA

1

IN AMAZONIA

Dreams of AvariceâMy Heart Goes Bump!âLandscape as Text ⦠and as BiographyâIgarapé GuaribaâAnother DiscoveryâEnvironmental Determinisms and Narrative AcrobaticsâSpaces of NatureâA Natural HistoryâCollecting and ReflectingâTraces of TraumaâSawdust Memories

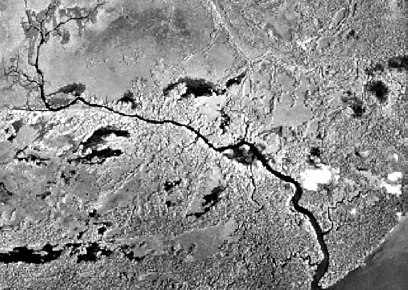

Let's begin in 1976. It was late summer that year when a crew from the Companhia de Pesquisas e Recursos Minerais, the geological survey of the Brazilian Ministry of Mines, shot this infrared aerial photograph of the Rio Guariba, by then almost a river. They didn't find what they were looking for, at least not here, although there was plenty of gold and magnesium close by. But their image is worth treasuring anyway. Its tactility holds this book in placeâexactly where it should be.

It was a famously hot summer in London. I was working in a gray stone warehouse in the East End docks, loading and unloading delivery trucks and stacking crates of beer and wine in tall towers on wooden pallets. That building is still standing, but like most of the warehouses down there it's been transformed: gutted, scrubbed, and converted into luxury condominiums. Back then, every Thursday, all the workersâtransients like myself and those hoping for the long haulâformed a snaking line up a narrow, deeply shadowed stairwell to a battered doorway on the top-floor landing. Every week, as the person ahead exited, I would knock on the closing door, enter the cramped office, and say my name to the company accountant seated behind a desk piled high with tumbling stacks of papers. And every Thursday, with the same motions and with the same half-smile, the accountant would calculate my wages, shuffle the money into a new brown envelope, and, as if to himself, repeat the same unsettling phrase: “Beyond the dreams of avariceâ¦.”

That same summer, an ocean away, in a world of which I still knew nothing, the Brazilian dictatorship was chasing avaricious dreams of its own. Late in 1976, as I grappled with an irony beyond my sensibility,

the generals were forcing convulsive inroads into their northern provinces, brushing aside Indian, peasant, and guerrilla resistance, creating fortunes, chaos, and despair. It was an aggressive territorialization, one that would radically change the dynamics and logic of regional politics and produce an unforeseen geopolitical re-siting that the military and their civilian successors have ever since struggled to disavow, a now-familiar ecological Amazonia subject to planetary discourses of common governance.

1

Meanwhile, between the contours of the military maps, people were making new worlds of their own. The survey image does not lie. Though we cannot see it yet, that river is growing, and in growing it transforms the lives that transform it. And the water that flowed past as I piled boxes by the Thames at Wapping Stairs where Jeffreys the Hanging Judge once attempted flight disguised as a sailor, that lapping water on which Ralegh was finally captured, his pockets stuffed with talismans of Guiana, and on which young Bates and Wallace, heading to Kew in 1848, talked of tropical travels soon to come, that murky water is the same rushing tide that washes in and out, a monstrous pump, sweeping the land out to sea and remaking this place I have called Igarapé Guariba.