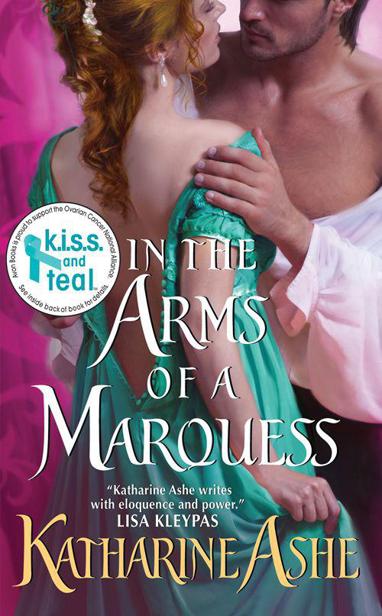

In the Arms of a Marquess

To the writers whose work inspires, teaches and strengthens me—

The light within me bows to the light within you.

And to my mother, Georgann Brophy.

Thank you, great lady and cherished friend.

Never attack a tiger on foot . . . for if you fail to kill him, he will certainly kill you.

—

WALTER CAMPBELL,

My Indian Journal

Contents

Madras, 1812

B

eneath a thick coating of sun, the port bazaar seethed with heat lifting off the ground in waves striated with dust. Pungent human bodies packed the street, dark-skinned, clad in white, yellow, and orange, working, shouting, begging, jostling. Music throttled the air, tinny pipe and the twang of plucked strings, harried and intricate. The young English miss, wrapped in wools that had seemed eminently practical on board ship, stewed like a trussed hare in a pot of boiling broth.

Yet none of it dulled the sparkle of wonder in her brown eyes or stilled the quick breaths escaping her lips. After years of dreaming, then months of shipboard anticipation, she was finally here.

India

.

Her uncle hurried the servants, snapping phrases at them in their language, ugly from his tongue but beautiful,

colorful

in the mouths of passing natives, a babble of incredible sound. Beads of sweat trickled under her tight collar and inside her gloves. She clutched her reticule under her arm and wrenched the gloves from her damp fingers, eyes alive, seeking everywhere, drinking in the sights.

Beneath awnings spread nearly to the center of the street, tables laden with market goods spilled into the narrow pedestrian passageway. Bins of vegetables, nuts, grains, and beans the hues of primroses, gardenias, violets, and moss competed for space with spools of fabrics in brilliant colors, shining silk and supple cottons, and barrels and clayware vats and bottles glistening with dark liquids. Vendors shouted and customers bickered, trading coins. A pair of skin-and-bones children, brown as dirt, darted between, a fruit seller hollering after them. The music grew louder from ahead, saturating the heavy air.

It was a marketplace such as she had never seen, chaotic and fluid so far beyond the market her mother frequented in London that it stole the breath from her young breast.

Behind the makeshift shops, buildings rose to modest height in impressive English elegance laced with exotic detail. Flanking the harbor the massive Fort St. George dwarfed them all, the presence of England so ponderously established upon this vast continent.

“I could not bring the carriage closer.” Uncle George turned and shook his head, his brow wrinkling. “And a chair is not to be found today. But the carriage is not far, just beyond the

bazir

. You there,” he ordered one of the servants, “run ahead and alert the coachman of our approach.”

The servant disappeared into the crowd.

The girl hoped the carriage was still very far away indeed. Nothing, not all of her reading and studying and every picture plate and oil painting she could see in London, had prepared her for the bone-rattling heat, the overwhelming scents of tangy, intoxicating spices mingled with unwashed humanity, or the sight of so many people, so much life, so much movement and color all on a single street.

After nearly sixteen years of life she had finally arrived in heaven.

Someone beside her stumbled, knocking into her, and she fell back, catching her knee on a crate. She stepped forward, but her dress clung, snagged on a jutting nail. Dropping her gloves onto the dirt-packed street, she tugged on the skirt. Her uncle’s hat was barely visible yards away, the servant gone. She yanked at the hem. It tore.

A tall man moved close. His thin lips curved into a grin, fist on his belt where a jewel-handled blade jutted in an arc from his loose trousers.

Her heart lurched.

Uncle George shouted for her as he pressed back through the crowd, but it flowed the opposite direction, pushing him away. The tall man drew forth the dagger and gestured with it. Someone gripped her upper arm. She whirled around. A swarthy face loomed inches from hers.

“Uncle!” she screamed, but the music seemed to swell, swallowing her cry.

“Come easy,

memsahib

, and you will not be harmed.” The dark man’s voice seemed sorrowful, belying his grip.

“No.” She struggled. “Unhand me!”

The man’s head jerked aside, his eyes opening to show the whites all around. He released her and dropped back. Just as abruptly, the tall native sheathed his dagger, his wary gaze fixed over her shoulder.

She tried to turn. Big hands cinched her waist, a voice behind her snapped terse foreign words, and then in the King’s English at her ear, “You are safe. Now up you go,” and he lifted her aloft.

With an

oomph

shot from her lungs, she landed upon a horse’s back. She gripped its tawny mane as the animal’s master vaulted into the saddle behind her. She teetered, but a strong arm wrapped around her and a long flash of silver arced over her head. The horse, a large white muscular animal, pressed forward.

She caught up her breath. “Sir—”

“Your uncle’s carriage is ahead a short distance. Allow me to escort you there.”

He slid his sword into its sheath at his hip, and her gaze followed the action. Sleek with muscle beneath fine leather breeches, his thighs flanked her behind, holding her steady like his arm tight around her middle. An arm clad in extraordinarily fine linen.

Her heart pounded. She twisted her chin over her shoulder and her gaze shot up.

“Sir, I must—”

Her protest died.

Eyes like polished ebony, long-lashed, warm and gently lazy, glinted down at her from beneath straight brows and a careless fall of black hair. His mouth curved up at one corner, a crease forming in his bronzed cheek.

“You must loosen your grip upon my horse’s mane,” he said softly, a hint of music in his gentleman’s perfect English, “or you will come away with a handful of hair, and he with a frightful bald spot.” A flash of white teeth animated a quick, boyish grin.

Why, despite his broad shoulders and splendid mount, he could not be very much older than she, perhaps only by a few years. And he was laughing at her, albeit nicely.

“I—” She pried her fingers open then grabbed at the silver-encased pommel digging into her thigh. The crowd seemed to part before them, but he was not watching their path. He was watching her, from very few inches away. Fewer inches than she had ever been separated from any man.

“I—” Words would not form upon her thick tongue, certainly a first. A whiff of scent tangled in her nostrils, leather and fresh linen and something else. Something subtle, like sandalwood but spicier, and . . .

wonderful

. Her palms went unaccountably damp.

“You?” His steady gaze gently smiled.

“I— I have torn my dress.”

His glance flickered to her thighs jammed between his knee and the animal’s withers, paused, then slowly traced her legs from hip to foot, and back again. She ceased breathing, every inch of skin beneath her gown tingling where his gaze passed.

He returned his regard to her. His eyes glimmered with laughter, but his shapely mouth slid into a serious line.

“I daresay you have.”

His grip on the reins shifted and he averted his face as he turned the horse’s direction. A glimpse of man’s neck showed above his cravat. She dragged her attention away, fixing on his hand beneath her ribs. It was a man’s hand, large and powerful, grasping the leathers with practiced ease, an enormous gold tiger’s head ring on one finger, ruby eyes flashing.

Perhaps he was rather a bit older than her, after all.

Tickles fluttered in her belly. And somewhat lower. She blinked.

The noise and closeness of the bazaar fell away, in its place open street, clean shop fronts, a pair of English officers like those she had traveled with all the way to India, and finally a carriage, her uncle’s servant standing before it.

“Your destination.” In one smooth movement her rescuer dismounted and drew her off the horse. She wavered, gulping breath. He ducked his head to peer beneath her bonnet brim. “Have your bearings now?”

She nodded, mouth dry. His hands slipped away from her waist, and he put his foot in the stirrup and mounted. Taking up the reins, he gestured behind her as his horse’s head swung around.

“Your uncle arrives.”

Uncle George shoved from the crowd into the cross street, his brow taut. He peered at the horseman, frowned, and strode forward.

The young man’s watchful gaze remained upon her.

“Sir.” She sounded oddly breathless. “Thank you for your assistance.”

He bowed from the saddle, his gold-embroidered waistcoat and the hilt of his sword sparkling in the sun falling in slanting rays behind him.

“It was my great honor.” His mouth quirked into a grin and the horse pranced a half circle. “Welcome to India,

shalabha

.” The beast wheeled away, stirring up a cloud of dusty street. She stared through the cloud. When the dust settled, he was gone.

“Dear lord, niece, I thought I’d lost you.” Uncle George gripped her hands, then cinched her arm under his and drew her toward the carriage. “Why didn’t you keep up? Are you unharmed? What did he want of you?”

“He rescued me. I snagged my dress and a pair of cutpurses accosted me, just as on a London street. It was fantastic.” And terrifying. Momentarily. “But he frightened them off.” Even though he certainly was not much bigger than either of the thieves, although he was quite tall. “He had the horse, however. A very fine horse. And a sword. A sword must count for more than a dagger, after all.”

“A dagger? Good God. Those men were not cutpurses. The

bazir

is not safe for Englishwomen. You may not go there again. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Uncle,” she said, shifting her gaze between him and the servant. The men exchanged peculiar looks. Uncle George handed her up the carriage steps. She settled into the seat, her heartbeat slowing but her limbs suddenly shaky.

“Uncle George, who was that young man?”

“His uncle owns the villa beside your brother-in-law’s house,” he said in short tones.

“Oh.” She was still two years from being out in society, but her sister’s husband, Sir St. John, always said the rules were rather more relaxed in the East Indies than at home. And the community of English traders in this part of India was quite small. If she and her rescuer were neighbors, she would certainly meet him again soon. Her stomach jittered with anticipation.

Uncle George climbed in and closed the door. Beyond the open sash, the

bazir

teemed with people, vibrancy, and sound. She worried her lip between her teeth and a shiver of delayed relief glistened through her. It would be lovely to return and explore the stands and shops, the next time much more carefully, now that she knew villains lurked about. Fortunately, so did dashing young English gentlemen.

“Uncle, what does

shalabha

mean?”