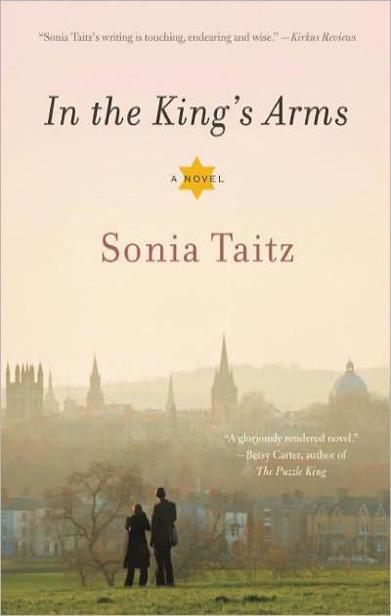

In the King's Arms

Read In the King's Arms Online

Authors: Sonia Taitz

Table of Contents

Praise for Sonia Taitz

“Sonia Taitz is an incisive, funny writer.”

—

People

People

“Wise, witty, and often hilarious.”

—

Publisher’s Weekly

Publisher’s Weekly

“Touching, sincere, endearingly besotted.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

Kirkus Reviews

Praise for

In the King’s Arms

In the King’s Arms

“Sonia Taitz’s witty, sensuous prose enlivens this tale of two cultures converging in Oxford in the 1970s. Lily of the Lower East Side, daughter of Holocaust survivors, falls in love with a son of the English gentry and is drawn into his family drama. Taitz deftly contrasts the lovers’ opposing worlds—and the surprising middle ground where they embrace.”

—Barbara Klein Moss, author of

Little Edens

Little Edens

“

In the King’s Arms

is a deeply felt, lyrical novel, at once romantic and mournful, that brings to life the long tentacles of the Holocaust through the generations. In Lily Taub, Sonia Taitz has created an unforgettable, believable and sympathetic character—the young girl in all of us. The author’s finely wrought observations about class structure in England, the vagaries of first love and the overriding possibility of redemption will stay with the reader long after finishing this book. ”

In the King’s Arms

is a deeply felt, lyrical novel, at once romantic and mournful, that brings to life the long tentacles of the Holocaust through the generations. In Lily Taub, Sonia Taitz has created an unforgettable, believable and sympathetic character—the young girl in all of us. The author’s finely wrought observations about class structure in England, the vagaries of first love and the overriding possibility of redemption will stay with the reader long after finishing this book. ”

—Emily Listfield, author of

Best Intentions

and

Waiting to Surface

Best Intentions

and

Waiting to Surface

“Who you are and where you come from are as indelible as the night, or in Lily Taub’s case, the darkest night imaginable. Trying to outrun her world, headstrong Lily escapes to Oxford where she

meets the gorgeous and aristocratic Julian Aiken—as English and Christian as she isn’t.

meets the gorgeous and aristocratic Julian Aiken—as English and Christian as she isn’t.

Always playing in the background of their torrid romance is her parents’ past. Her mother was raised in a concentration camp, and her father spent most of the war hiding beneath a barn in Poland, where overhead the “sweet cows” offered company and precious heat.

In her gloriously rendered novel,

In the King’s Arms

, Sonia Taitz writes passionately and wisely about outsiders and what happens when worlds apart slam into each other.”

In the King’s Arms

, Sonia Taitz writes passionately and wisely about outsiders and what happens when worlds apart slam into each other.”

—Betsy Carter, author of

The Puzzle King

The Puzzle King

Also by Sonia Taitz

NONFICTION

Mothering Heights

PLAYS

Whispered Results

Couch Tandem

The Limbo Limbo

Darkroom

Domestics (One Act Play)

Cut Paste Delete Restore

Couch Tandem

The Limbo Limbo

Darkroom

Domestics (One Act Play)

Cut Paste Delete Restore

To Professor John Simopoulos,

genie of Oxford and fellow traveler

genie of Oxford and fellow traveler

Love in its essence is spiritual fire.

EMANUEL SWEDENBORG

PROLOGUE

New York: 1975

T

HERE WAS A PLACE for everything, and everything was in its place but Lily. She had come to Europe in a great heat, pressing her attentions upon one of its most ancient institutions. To gain access to Oxford she’d had to get “A” after “A” every day of her schoolgirl life, then flag them at the Doorkeepers of Western Civilization. Years of sprawling across the desk with out-flung arm, pleading to be “called on,” annunciated by the teacher. And later, at college, her perfect papers: “well observed,” “sensitive.” Lily entertained the idea that she could amount to something spectacular. The Messiah, who had not yet arrived, could well be a woman, particularly in these times.

HERE WAS A PLACE for everything, and everything was in its place but Lily. She had come to Europe in a great heat, pressing her attentions upon one of its most ancient institutions. To gain access to Oxford she’d had to get “A” after “A” every day of her schoolgirl life, then flag them at the Doorkeepers of Western Civilization. Years of sprawling across the desk with out-flung arm, pleading to be “called on,” annunciated by the teacher. And later, at college, her perfect papers: “well observed,” “sensitive.” Lily entertained the idea that she could amount to something spectacular. The Messiah, who had not yet arrived, could well be a woman, particularly in these times.

Her poor old father had shelled out the necessary cash; he was so proud of his girl. It was two against one, and the mother had lost. She pushed together a heap of crumbs on the table. “Boy-o-boy, you’ll be some great lady,” said the father, as his wife (Lily’s mother) grumbled. He believed in providence, in “election,” in spirits that are suddenly whisked from corked flasks to do marvelous things. This was because of what had happened to him, how his own life had been saved, thirty years ago, in Europe.

“Great lady,” her mother finally said aloud, a sullen echo of her father’s blessing. It wasn’t jealousy. It wasn’t that the Nazis had ruined her education. She thought Lily was running away

from everything she knew. She thought Lily was running away from her.

from everything she knew. She thought Lily was running away from her.

Lily could see her point. They were sitting in their bright kitchen in the Lower East Side of New York City. Linoleum on the floor (a pick-up sticks motif in primary colors), tarnished pots and pans, daisy-patterned oilcloth, bird-drop on the sill. She looked at them and saw two elderly refugees. Modest, simple, straitened. Their shoulders seemed fragile under their clothes. They hadn’t come from Oxford-Europe. They’d come from Eastern Europe. Although they didn’t make the distinction; to them it was one bloody “old world,” medieval checkerboard.

Her mother was tattooed: blue digits on her arm. Lily used to be ashamed of this, and this disloyalty shamed her too. Even at her Jewish summer camp she’d been sickened by shame, at a place where you’d suppose the other kids had parents like hers. They didn’t: they had managed to find parents who played ball with them, who wore white sneakers and brought them bite-sized Snickers. Lily’s grey-haired (what was left of it) father would grab a snooze on her hospital-cornered cot, the Yiddish newspaper shielding his face from the very brightness of a New World summer. Mother wore ankle socks and sandals; she offered soft, sad bananas, or hard-boiled eggs (wrapped in scrunchy tinfoil). She’d grasp the counselor’s hand (her numbers went flying up and down, a blue whirl), and say “Senk you for vatchink mine Leely!”

They had raised their girl religiously: twelve solid years of yeshiva, to fortify her resistance to the outside world. Vassar College had been a frightening gamble, but it was in New York and reachable by car service. For years, Lily would not read the Bible in English; it seemed metallic, iced, pinched. Hebrew was dense and dark, like cello sounds, or chocolate. Melismatic melodies played in

Lily’s head. They came from the synagogue up the hill; from below the fuzzy beard of the rabbi who first read her Isaiah’s prophecies; from (as a child might say) thousands and thousands of years ago and far away.

Lily’s head. They came from the synagogue up the hill; from below the fuzzy beard of the rabbi who first read her Isaiah’s prophecies; from (as a child might say) thousands and thousands of years ago and far away.

At night she’d encounter anti-Semites in her shadowy bedroom, her parents’ tormentors. She’d reason them away, talmudically deft, stabbing her finger into the air, listening to their responses as she stroked her chin. She managed to dissuade the English from kicking all their Jews out in the 13th century. She sat on the Pope’s knee and tipped his skullcap to one side, so he looked like a merry-making Hassid. She converted the Spanish Inquisitors to the laws of

kashruth

: never again would they roast a Jew or eat paella. She made the Nazis cry: gosh, we’re sorry! What in God’s name came over us? The best part was forgiving everybody. “Oh, that’s all right,” she’d say aloud, magnanimously, “Just see that you behave from now on.”

kashruth

: never again would they roast a Jew or eat paella. She made the Nazis cry: gosh, we’re sorry! What in God’s name came over us? The best part was forgiving everybody. “Oh, that’s all right,” she’d say aloud, magnanimously, “Just see that you behave from now on.”

In a way, at twenty-one, Lily had grown deeply exhausted of the Jewish mania: a world consisting of Jews and non-Jews, the former radically monotheistic, ennobled by fires that cannot consume, messianic. And blessed with smarts. Her father had once said, “the dumbest Jew is smarter than the smartest goy.” Of course, the goyim he couldn’t forget were

muzhiks

: gap-toothed potato-heads with leering mugs. And her mother had a tendency to rattle off the following catechism: “Einstein Freud Marx Proust Mahler Mendelssohn Chagall and don’t forget Dr. Jonas Salk, without whom they would all be cripples. And still they hate us!”

muzhiks

: gap-toothed potato-heads with leering mugs. And her mother had a tendency to rattle off the following catechism: “Einstein Freud Marx Proust Mahler Mendelssohn Chagall and don’t forget Dr. Jonas Salk, without whom they would all be cripples. And still they hate us!”

But in a way, and quite by nature, Lily was a Jewish maniac herself. The life she was living in America, relentlessly fair-minded, sane, secular, was, for her, mediocre. It offered no existential standoffs, no life-and-death crises. Even her parents seemed to soften and blur under equitable American skies. Lily was prime for zealotry.

She had none of their hard-won mildness. She had the memories only, without resolution.

She had none of their hard-won mildness. She had the memories only, without resolution.

People often wonder how those who went through what Mr. and Mrs. Taub went through could be so “well-adjusted.” They were. Three decades after liberation, they casually alluded to the nightmare over crullers and coffee. Lily’s mother sported jeweled bracelets on her numbered arm and wafted perfume from shoulders that brutal German men had beaten; she and her husband went out waltzing every Saturday night. It felt strange when Lily looked at her baby pictures, taken by her parents, knowing that their own pictures had been burned, that their parents themselves (her missing grandparents) had burned to anonymous ash and blown away. But they never thought of the pictures that way; they loved the pretty pictures. It was Lily who was blindly chasing ghosts.

Another thing about Oxford. The obvious:

Kultur

. God knows, Lily was a snob! She didn’t hold with her father’s smart-Jew-dumb-goy philosophy. Quite the contrary. The Anglo-Christian empire had sunk its stake into her imagination as soon as she read

Hamlet

(on a typical, schizoid yeshiva day in which she’d had Torah before lunch and Shakespeare directly after). She loved the romance of it; she loved the idea of times out of joint, of deaths avenged and unavenged. She had been conquered, too, by “Art History” with its painted crucifixes, and the image of the mother bereaved. She loved the strength of Renaissance brass, and the moody words “heath” and “moor.” She curled up to regal, passionate Lord Byron. When he spoke of Asia, or George Eliot of Zion, or Blake of Jerusalem, their sudden intimacy made her shiver. Presumption inflamed her.

Kultur

. God knows, Lily was a snob! She didn’t hold with her father’s smart-Jew-dumb-goy philosophy. Quite the contrary. The Anglo-Christian empire had sunk its stake into her imagination as soon as she read

Hamlet

(on a typical, schizoid yeshiva day in which she’d had Torah before lunch and Shakespeare directly after). She loved the romance of it; she loved the idea of times out of joint, of deaths avenged and unavenged. She had been conquered, too, by “Art History” with its painted crucifixes, and the image of the mother bereaved. She loved the strength of Renaissance brass, and the moody words “heath” and “moor.” She curled up to regal, passionate Lord Byron. When he spoke of Asia, or George Eliot of Zion, or Blake of Jerusalem, their sudden intimacy made her shiver. Presumption inflamed her.

She sensed all along that what she wanted, in leaving the familiar, was not just abstract, but impossible. Lily wasn’t going to recreate the fierce “Old World” anywhere. Oxford, in any case, while

perhaps medieval, perhaps Victorian, was coolly removed from the passion of blood-hatred. She couldn’t bring her past to it or it to her past. Even the little things she brought over to “brighten up” her room looked flat and small and lonesome there. Somehow the truth kept getting lost in the Atlantic Ocean, traveled either way. Lily might have believed in the impossible, but she couldn’t hold both ends of it at once.

perhaps medieval, perhaps Victorian, was coolly removed from the passion of blood-hatred. She couldn’t bring her past to it or it to her past. Even the little things she brought over to “brighten up” her room looked flat and small and lonesome there. Somehow the truth kept getting lost in the Atlantic Ocean, traveled either way. Lily might have believed in the impossible, but she couldn’t hold both ends of it at once.

With one exception.

1

Europe, 1976

W

HEN LILY FIRST SAW HER ancient college room, she felt doomed. It smelled of puke and mildew; a chipped sink gurgled dyspeptically in the corner. Her narrow bed was covered in what looked to be tartan burlap (not the generous, lumpy, duvet-smothered, stuffed-pony bed she’d envisioned). She saw a thousand wretched nights ahead, Oliver Twistian nights in which she’d go to sleep squirming and loveless and lost.

HEN LILY FIRST SAW HER ancient college room, she felt doomed. It smelled of puke and mildew; a chipped sink gurgled dyspeptically in the corner. Her narrow bed was covered in what looked to be tartan burlap (not the generous, lumpy, duvet-smothered, stuffed-pony bed she’d envisioned). She saw a thousand wretched nights ahead, Oliver Twistian nights in which she’d go to sleep squirming and loveless and lost.

Other books

The Exchange of Princesses by Chantal Thomas

You, and Only You by McNare, Jennifer

Whispering Nickel Idols by Glen Cook

Burning Chrome by William Gibson

Heaven Eyes by David Almond

Obsidian Sky by Julius St. Clair

The Tao of Dating: The Smart Woman's Guide to Being Absolutely Irresistible by Dr. Ali Binazir

14 - The Burgundian's Tale by Kate Sedley

BILLIONAIRE (Part 6) by Jones, Juliette

Slightly Shady by Amanda Quick