In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (13 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

I noticed the formation of the (Russian) word

shveytsarskaya

(porter's lodge) which I had seen many times, and of the word

kondityerskaya

(confectioners shop). This -

skaya

interested me and showed that suffixes provide the possibility of making from one word a number of others which don't have to be learned separately. This idea took complete possession of me. I began comparing words and looking for constant, definite relations among them, and every day I threw large series of words out of my dictionary and substituted for them a single suffix defining a certain relationship.

At about the same time, he began to study English in school. For a speaker of Russian, with its complex systems of verb conjugation and noun agreement, its accusative, genitive, locative, and other sundry cases, English must have appeared a dream of simplicity. He felt the freedom of gliding over ice-smooth paradigms—“I had, you had, he had, she had, we had, they had”—and purged his nascent language of unnecessary grammatical markers.

On December 17, 1878, a Proto-Esperanto congress convened. Despite his shyness, Ludwik had convinced some of his schoolmates to involve themselves in his project. They gathered in his cramped apartment to celebrate over cake and take part in that most Esperanto of activities—the singing of hymns. On this day they sang a poem by Ludwik that succinctly captures the sentiment that inspired his diligence:

Malamikete de las nacjes

Kadó, kadó, jam temp està

La tot’ homoze en familije konungiare so debà

.Enmity of nations

Fall, fall, the time has come

May the whole of humanity be united as one.

This poem is an example of early Esperanto. The language was further tweaked and modified when Ludwik was forced to reinvent it from scratch. Before he left for university to study medicine, a colleague of his father's had remarked that Ludwik seemed awfully wrapped up in this language of his. Fearing that it would distract the young man from his studies, Marcus demanded that he leave it behind. The compliant son handed over his lovingly filled notebooks, and some time after he set out for Moscow, his father threw them on the fire. Ludwik didn't discover this until he transferred home to the University of Warsaw. But he had no time to brood. Soon the enmity of nations bubbled up into a wave of violent pogroms that swept through Russia, including a two-day spree of bloodshed in Warsaw. More determined than ever, he started all over again.

In the next five years he finished his education and began his practice as an oculist, general medicine having proved to induce debilitating guilt when he couldn't do anything to help a patient. He continued revising and refining his language, and he met his future wife, Klara. She embraced him and his language, and they used it to write love letters to each other.

The official birth of Esperanto occurred in 1887, the year that Zamenhof, using Klara's dowry, self-published a small book titled

Lingvo internacia

. He modestly declined to attach his own name

to it, signing it instead Dr. Esperanto, meaning “one who hopes.” He explained inside that an “international language, like every national one, is the property of society, and the author renounces all personal rights in it for ever.” Ludwik and Klara packaged the books and sent them into an unsympathetic world.

Nothing says success like bitter, angry jealousy in the hearts of your competitors. In this case, the names read like the product of the perverted etymological strategies of the modern-day pharmaceutical industry: Interlingua, Ido, Glosa, Globaqo, Novial, Hom-Idyomo. These are just a few of the many languages proclaimed by their advocates to be simpler, more logical, and more beautiful than Esperanto. But Esperanto can afford to be smug. It's the only one you've heard of.

And this drives the other guys nuts. When I first became curious about the topic of constructed languages, I joined a Listserv called Conlang. The next day my in-box held 287 messages. After a few days of this, I decided I wasn't that interested and unsubscribed. I didn't know that I'd innocently stepped right into the “flame war” that ultimately led to the “great split,” after which things calmed down considerably.

The split was between two groups. The first was composed of people interested in quietly developing and discussing the languages they crafted for science-fictional worlds, what-if-a-language-did-this playfulness, or Tolkienesque fun (the true conlangers). The second was composed of those who wanted to talk about an international auxiliary language for the real world (the auxlangers). The auxlang group included a few devoted Es-perantists and a larger number of supporters of alternate projects. Most of the war was conducted within the auxlang group,

as vitriol hurled at Esperanto for its “totally ridiculous spelling system,” “the backward and confusing affix system,” and “the accusative -n abomination.” Additional fighting took place between the various Esperanto competitors—Ido took on Interlingua, and a new version of Novial took on an old version of Novial. The conlangers got fed up with “this stupid argument about something that is never, NEVER, going to happen anyway, FACE IT!!!” and the auxlangers, no doubt tired of being called “deluded lunatics” in the one place it was supposed to be safe to talk about invented languages, agreed to split off and form their own list. The conlangers went back to tame exchanges about tense-aspect marking and vowel harmony, and the auxlangers took it outside.

Every anti-Esperantist auxlanger is convinced that he (no need to fret about gender-neutral pronouns on this one) represents a superior product. Perhaps one of them does. Perhaps all of them do. It doesn't matter. At an Esperanto conference, I witnessed a tired-looking man in a gray T-shirt defiantly introduce himself as an Interlingua supporter. “I think it is a better language,” he announced. “It's clearer, more logical, and more beautiful than Esperanto,” and then, without the slightest trace of irony, “but I have no one to speak it with.”

Esperanto may never have risen to its position of prominence if it hadn't suffered its own great split early on. In the lore of Esperantoland, it is called the Schism, and if this makes you think of religious wars, you aren't far off. The Schism served to draw off the people who were interested in the language itself (the prestigious scholars with linguistically sophisticated suggestions for improving and perfecting it) from the people who were interested

in the idea behind the language (the idealistic true believers, or, depending on whom you ask, the kooks).

Zamenhof was an amateur. He had no training in philology, no university chair. But because he was driven by the serious (if naive) hope that his language would help society, he devoted his energy to persuading people to use it rather than convincing them to appreciate its design. His book had included a form for the reader to sign, agreeing to learn the language if ten million others also signed the form. Fewer than a thousand came back, but enough interest had been generated to inspire him to translate the original Russian text into Polish, French, and German. He left the English translation to a well-meaning German volunteer, who produced choice manglings such as “The reader will doubtless take with mistrust this opuscule in hand, deeming that he has it here to do with some irrealizable utopy.” Before its chances were completely killed in the English-speaking world, an Irish linguist took interest and produced a more readable translation.

The book laid out a grammar of sixteen rules and a lexicon of about nine hundred words. Though the lexicon has grown considerably since then, the basic structure of the language has remained essentially unchanged to this day. Words are formed from roots and affixes. Nouns end in -

o

, adjectives in -

a

, adverbs in -

e

:

The verb endings differ with tense:

Other endings modify the meaning in different ways. The feminine is formed with -

in

, diminutives with -

et

:

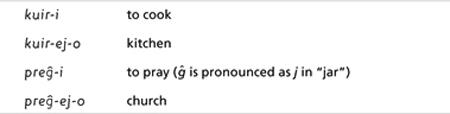

The Russian -

skaya

(place for) that had inspired Zamenhof to build words through affixation became -

ej

(pronounced “ey”):

The opposite sense of a word can be formed by prefixing

mal

-:

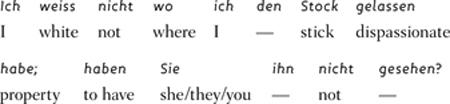

These, among other affixes, extend the range of the relatively small vocabulary of roots provided in the book. The affixes never change their form, so they are always recognizable. You can always at least tell whether a word is a noun or an adjective, whether a verb is past or present tense. The roots never change their form when they join to an affix, so you can always find them in the dictionary. This is not the way most languages work. Zamenhof gives an example from German, with the translation you would get if you looked it up word for word in a dictionary: