In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (18 page)

Read In the Sanctuary of Outcasts Online

Authors: Neil White

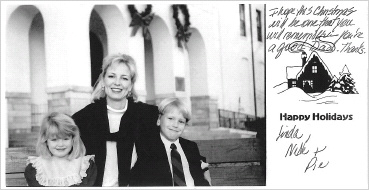

The Christmas card from Oxford.

Every day after the four o’clock stand-up count, the Dutchtown inmates gathered on the ground floor of our unit for mail call. As the guards called my name, I felt a bit guilty about the amount of mail I received. I had reached out to every remaining friend. And my mother, who had a knack for galvanizing people into action, had encouraged all her friends to write, too. I received dozens of magazines, three daily newspapers, and a regular supply of books and letters. Most, I’m sure, orchestrated by my mother’s asking friends to write.

And Mom was particularly proficient, too. She sent newspaper clippings and snippets about my former interests. She wrote about the births and marriages of friends and acquaintances. She sent photos of our family. And though the photographs were, at times, exciting to receive, they also reminded me of the moments I was missing.

I received a Christmas card from Linda. The photograph, of Linda and the kids in front of the courthouse in Oxford, was stunningly beautiful. Wreaths with red bows had been hung between each white arch of the courthouse facade. The photograph was taken on a cool day in the late afternoon. Bits of sunlight illuminated the courthouse walls between the shadows cast by the leafless limbs of the oak trees. Linda, arms wrapped around the children, wore a thick white sweater with a dark peacoat and scarf. Maggie wore a red velvet dress with a lace collar. And Little Neil wore a blue blazer with a red-and-blue striped tie.

It was the saddest Christmas card I had ever received. It was my family without me.

One thing was clear. She was moving on. I put Linda’s card in my locker and took off my wedding ring.

I wanted to perform some kind of ceremony. I imagined I would dig a small hole in the ground somewhere on the colony grounds. A burial. I would leave the symbol of our marriage here, where it ended, at the colony. But what if, by some miracle, we got back together? If I left the ring buried on the grounds, I’d never be able to retrieve it.

So instead, I placed my wedding band inside an envelope. I sealed it and wrote on the outside, Wedding Ring. I found an empty slot in the back of the expandable file folder Doc had given me, and I buried the envelope deep inside.

My nightmares about the children persisted. In every dream, Neil and Maggie were falling from a building or a tall tree or a window in an apartment. The setting changed, but there were two recurring themes: I could never quite reach them, and I could not see the ground. And at the end of each dream, like the swinging bridge nightmare, my children fell into an abyss. I would sit up in bed, wailing, covered in sweat.

Doc even got used to it. He would groan and put a pillow over his head. On the nights when the dreams came to me, I would climb out of bed and walk the corridors until it was time for work.

Ella noticed the bags under my eyes.

“Nightmares,” I told her. “Ever have them?”

“Musta,” she said, “just don’t remember.” But Ella did tell me about another dream.

“I’m just a little ole thing,” she said. “My momma holds me like a baby.”

In the dream, Ella’s mother held her against her breast, rocked her in an old wooden chair, and sang hymns. Ella got tickled. “She tryin’ to get me to go to sleep, but I’m already asleep.”

“I be all warm,” Ella said. “I’s a baby, but Momma already know I got this disease.”

Ella’s dream had a recurring theme, too. Her mother said the same words.

“Momma say, ‘

You got what Jesus talk about in the Bible. I wouldn’ta throwed you out.

’” Ella smiled. “Then we both laughs, and I goes to sleep.”

Listening to her describe this dream, watching her laugh, witnessing the way she held herself, I realized that, somehow, Ella had escaped the shame of leprosy.

I’d read about a brief period in medieval Europe when some Christians considered leprosy a sacred disease. Infection, among the most devout, was seen as a privilege. Being a leper, one of Christ’s poor, meant a sufferer need not wait for any rapture. Resurrection occurred immediately. The belief that leprosy was a godly disease was so widespread that Lazar houses and leper colonies were like monastic retreats. One European prince proclaimed that putting his hands on an outcast, washing the open wounds on a leper’s feet, would get him one step closer to heaven. And Father Damien, the Martyr of Molokai, had perpetuated that conviction. He said that if he were to contract leprosy—which, in the end, he did—he would gain a “crown of thorns.”

But this view of leprosy had disappeared. Over the last five centuries, leprosy, and all the stigma that goes with the disease, found its way back into the human psyche.

But Ella carried her leprosy like a divine blessing. She had faith that she would be healed in heaven. She embraced the life she believed God had chosen for her on earth. She had transcended the stigma that crippled so many.

Mom brought Maggie and Neil to visit as often as possible. Our hours together in the visiting room were a precious time. As we played and talked, my mother sat quietly in the corner and read. She could not have given me a greater gift than those moments with my children.

When Neil and Maggie weren’t on the road to see me, I wrote letters reminding them that “Daddy’s time-out” wouldn’t last much longer. I wrote about the exciting things we would do together when I was released.

I created two comic strips with Neil and Maggie as the superheroes. Maggie’s comic was entitled

Magalina Ballerina

. The heroine was a four-year-old girl who used ballet moves to fight crime and save her friends from danger. Neil’s comic was entitled

Hoverboard Boy

. The hero, Little Neil, used his superpowers and a hoverboard—a flying skateboard like the one used in the

Back to the Future

movies—to save the world from evil.

As I was illustrating one of the comics, Steve Read looked over my shoulder and snorted. It might seem a bit strange to see a dad in prison dreaming up plots where his children fought crime, but, then again, I didn’t feel like a convict when I was being a father.

“Have they captured any check kiters yet?” Steve said.

Steve could be a real ass. But he was funny, too.

When I wasn’t writing to, and illustrating comics for, Neil and Maggie, I wrote to everyone I ever knew. I wrote to the victims of my crime to apologize, to make amends, if they could imagine some way for me to be helpful. I wrote to old college buddies. I wrote to

old girlfriends. I wrote to former employees. I wrote to high school teachers. I wrote to other journalists and writers. I wrote to friends of my parents. I wrote to Judge Gex. I wrote to my buddy Willie Morris. The return address on my letters included my inmate number, as well as Carville’s address.

Some afternoons after mail call, Link would follow me back to my room to watch me open my envelopes. At times, he asked me to read my letter out loud. He particularly enjoyed my mother’s letters. He thought her expressions were hilarious.

“What’d you get today, Clark Kent?” Link asked.

I held up a copy of the

Wall Street Journal

and

USA Today

, a couple of magazines, a package from my mother, and a letter from my old friend Willie Morris. Months earlier, when I was still in the denial phase, I had written Willie and described some of the characters living in Carville. I explained my George Plimpton–esque plan, and asked if he knew any editors who might be interested in a participatory journalistic piece. Willie knew just about everyone in the literary world. He was vaguely encouraging, and he suggested that I just continue to write. Willie was too kind to point out the absurdity of pretending to be an undercover journalist during a prison term, but his tone said it all. He had lost the enthusiasm he had for me earlier in my career.

Despite the mood of the letter, I was proud that he had written me. “Willie Morris,” I told Link, “is one of the great living southern writers.”

“What he write?” Link asked.

“

North Toward Home

.

Good Old Boy

.

The Courting of Marcus Dupree

. He was editor of

Harper’s

magazine at age thirty-one.” Link didn’t look remotely impressed. “The youngest ever,” I added.

“Another borin’-ass, white motherfucker,” he said.

I tore open the large manila envelope from my mother. It was copies from another self-help book. A note was scrawled in a corner—that I should never forget how precious I was. Mom’s handwriting was terrible, primarily because she was always in a rush. She once

made our school lunch sandwiches so hurriedly she left the plastic wrappers on the Kraft cheese slices.

Link sat on the side of one of the bunks. He was quiet, which was unusual.

“Anything wrong?” I asked.

Then he blurted out, “Write me a letter.”

“Sure,” I said.

“To my mama.” Link’s mother had come to the visiting room, but he had always refused to see her. He told me all she wanted to do was read the Bible to him. Eventually, she quit coming. I took out a pad and pen and told Link I would be happy to write a letter on his behalf.

“I’ll write,” I said. “You dictate.”

“Dick what!?” he said.

“You talk and I’ll write.”

“Why the

fuck

didn’t you say that!”

I wrote the salutation and read it, “Dear Mom.” Then I asked Link what he wanted to say.

“You writin’ it,” he insisted. “Say whatever the fuck you want.”

Link refused to offer any text, so I wrote, on his behalf and spoke aloud:

Dear Mom: This place is like a country club.

Link smiled and nodded.

I’ve made some friends while I’ve been here. The guy writing this letter for me is one of them. I call him Clark Kent. He is the whitest man you will ever meet.

“That’s good,” Link said.

I continued:

I play lots of cards and dominoes. And I help leprosy patients in the cafeteria.

I continued to write, as best I could, about Link’s days—until he finally offered to help.

“Ask her this…,” he said, hesitating, like he might be embarrassed. “Ask her how Ashley is.”

“Who’s Ashley?”

“My little sister,” he said. I could tell he really cared about her, and he wanted to know what she’d like for Christmas. He wanted to

know what she was doing with her friends. And he warned her not to get in the car with a guy named Little Feets.

“Do you want me to ask if Ashley will come visit?”

“Yeah,” Link said, pointing at the pad. “Write that down.”

I finished the letter, addressed and stamped the envelope, and told Link I would mail it in the morning.

“Hey,” he said, “it’s OK if you write all that shit I told you.”

I nodded and shrugged.

“No,” he said, “I want you to.”

“Maybe someday,” I said.

“Don’t wait too long,” he said. “Life span of a nigger in my neighborhood is short.”

“Hey, Doc,” I asked, interrupting his reading, “what are you going to do when you get out?”

“Leave the country,” he said.

Doc rambled about the FDA’s enforcement of U.S. laws and said he would never subject himself to their interpretations again.

“Where will you go?”

He thought for a moment. “Latin America might work.” Doc added that Hispanic men viewed impotence as a direct reflection of their manhood. “But my heat pill has other applications.”

Doc’s heat pill perfectly mimicked fever. Fever was the body’s natural mechanism for fighting infection and disease. Other thermogenic compounds might raise the body’s temperature a degree or two, but Doc’s heat pill had no limit. That was its great potential, as well as its danger. An overdose would cook a patient from the inside. But regulated and supervised by a doctor, it could generate enough heat at a cellular level to kill just about any bacteria. And no other physician on earth had as much experience with the thermogenic agent DNP as Doc. He had observed its effects in thousands of patients at his weight loss clinics. Over the years he had developed the art of dosage and frequency. And he discovered hormone supplements to reduce side effects and get the greatest results.

“You know,” Doc said, nonchalantly, “the AIDS virus dies at 107 degrees.” When I asked for details, he explained that the virus could live outside the body for about seven hours, but it died within minutes

of exposure to 107-degree heat, and his heat pill could produce those kinds of temperatures.

“You’ve got to tell somebody,” I said.

But Doc had no intention of telling anyone about the potential benefits of his heat pill. At least not until he was a free man. He couldn’t profit from its use as long as he was incarcerated.

A few minutes later, Doc said, “It’s not just AIDS.” His heat pill could potentially cure Lyme disease, several forms of cancer, and just about any other infection sensitive to heat. Doc said his pill could even save lost mountain climbers. If they carried a couple of his pills, the thermogenic effects would prevent frostbite for days until rescuers arrived.

“What about leprosy?” I asked. Leprosy preferred the cool parts of the body. If Doc’s pill generated heat within the cells, it would certainly kill

Mycobacterium leprae

.

“I guess it would work,” Doc said. He seemed less than enthusiastic. Victims of leprosy, for the most part, lived in underdeveloped nations. It attacked the malnourished, the poor. They didn’t have the resources to buy Doc’s heat pill.

Sometimes, late at night, in the fuzzy state between sleep and consciousness, Doc would think aloud. In a groggy voice, he would question the logic of confinement or speculate on a new prison regulation or contemplate a recent scientific discovery.

“Doc,” I asked, not knowing if he was asleep or not, “can your heat pill really cure cancer and AIDS?”

“Maybe,” Doc said. “But I’ve been thinking a lot about growth hormones.” The room was quiet for a moment, then Doc asked what I thought would be the best market for growth hormones.

The largest was obvious. “Asia,” I said. “China’s got a billion people.”

“Yeah,” Doc said, “short little fuckers over there.” He pulled the gray blanket over his shoulders and turned toward the wall.

I lay in the dark a few feet away from a man who could, conceivably, cure any number of humanity’s dreaded diseases. But he had no intention of sharing the cures with anyone. Doc was biding his time.