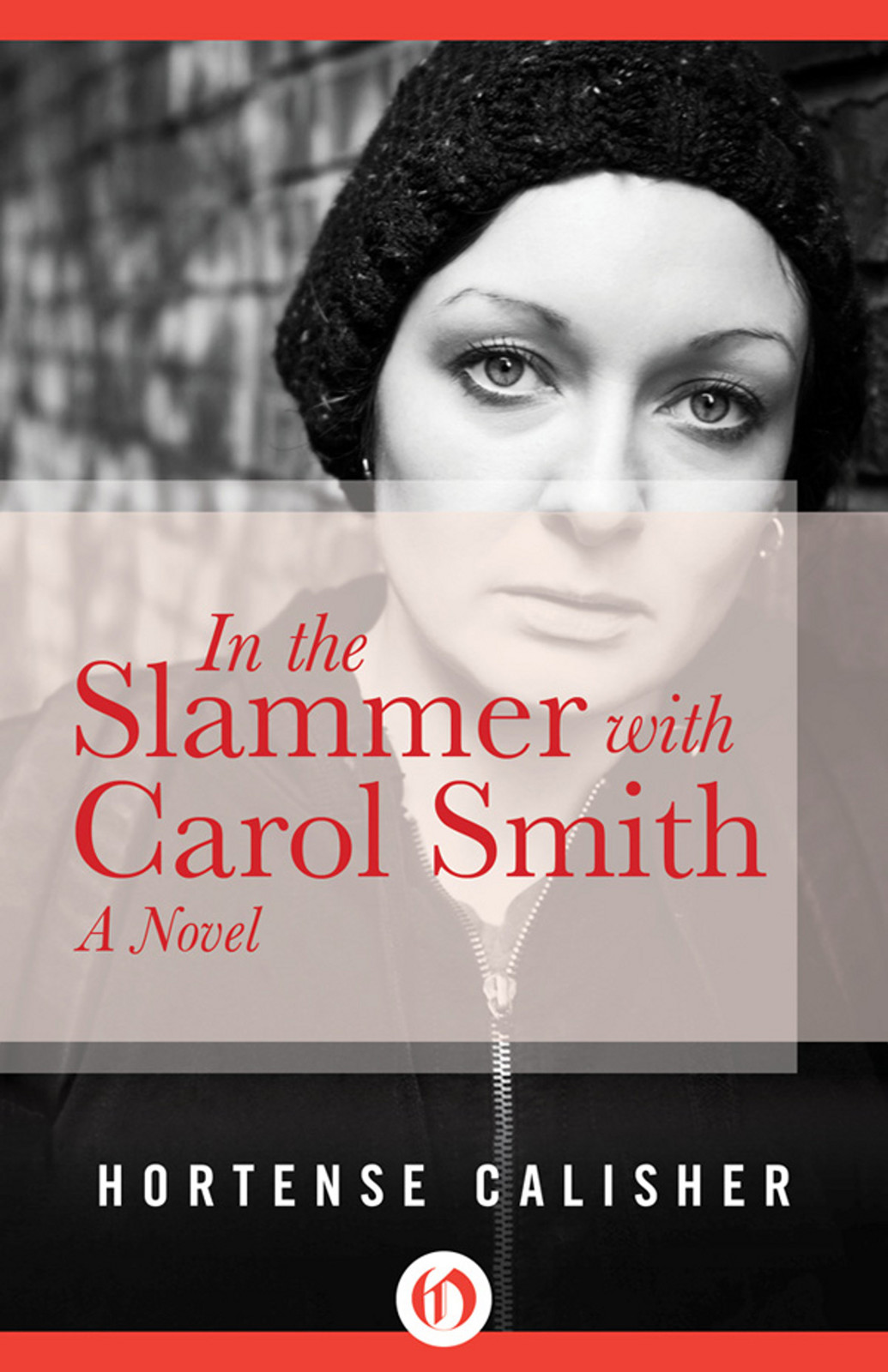

In the Slammer With Carol Smith

Read In the Slammer With Carol Smith Online

Authors: Hortense Calisher

A Novel

Hortense Calisher

A

LPHONSE WAS MY

wino friend; when he was off the sauce he still thought he was an actor. That’s the wrong way round for a wino; it’s when you’re high you’re supposed to give yourself airs, but the wrong way round is what we people are. He and I met leaning out to look at the river, in that jog the West Side Highway takes before the cars go back on Riverside Drive, Seventy-second Street. He thought I was normal because I still had the bike.

‘This wall—they got it just right for leaning,’ I said. With some guys the woman has to speak first. He had a thin, Picasso boy’s profile; that’s why I could. And it was true about the wall. Stone. The right height for most elbows. The city fathers must have put it up a long time ago.

‘You a college girl?’

I was pleased. When I am, I can speak the truth; when I’m angry, it goes off. And I still do wear my hair that way, long. Pinned with the barette. ‘I was, once. I’m twenty-eight.’

‘I’m an actor.’

Right then I thought: he knows. That what I am is what I do. That all the profession I have is to go on being that. Else why would he fling out this way, with what he is?

‘Character?’ I say. What other kind of actor could he be, with that Adam’s apple, and the skinniness? Unless he was a transvestite—which I didn’t think.

‘Some. I’m on unemployment.’

‘Gee. That’s the cream.’ Did I believe him? I think I didn’t, even then. Takes one to know one. But I gave him the advantage. Like he is giving me.

‘Not that easy,’ he says. ‘Not as easy as you think.’ He’s repeating, see, for confidence. Sometimes it makes me feel sad, seeing others using my same tricks. Sometimes it makes me feel safe. Like if I cared to, I could have a relative. I wouldn’t of course. It isn’t that safe.

But I can’t help giving him the look—like he’s a high class dog I might be thinking to buy. Or like at someone who might buy me. ‘I don’t know any you unemployment footdraggers anymore. I’m on welfare. A branch of it.’

He nods. Maybe he is too. If he is, he knows that family welfare is not the only kind. And that I’m not any widowed mother or healthy dependent. It’s not just an informal once-over he’s giving me.

‘What you looking at?’ It burst out of me. I can never help it. It’s what we all say, when people look too long.

‘I’m not,’ he says too quick—as if he knows that. ‘I’m looking at the bike.’

‘It’s an Italian racer. Until it got too rusty it used to fold.’ I don’t like to own things, except for the barette. So when I socked half the disability allowance for the bike, my SW was too encouraged. ‘Guy in a garage I know gave it to me,’ I told her. ‘It was left.’ But she wasn’t fooled; maybe she passes by that thrift shop window on the way to me. ‘Oh Carol, that’s real health,’ she said. And gave me an allowance replacement because she knew I wouldn’t ask. For a social worker, she’s not bad.

‘How many speeds it have?’

‘I don’t know. I’ve never let it out.’ I don’t ride it, only walk it. But it looks so good. So me, as I ought to be. Like the barette. ‘Anyway, I don’t own it. Belongs my neighbor’s kid.’

He does give me the focus then. When he pulls the pint bottle out of his chino pocket, and sideswipes a slurp without even a gander at it, is when I cotton to what he is—and when he stashes it again. They never trust a bottle to any bag they may be carrying. ‘You shouldn’t say that to a stranger.’

‘Say what?’ But I already know what I shouldn’t have said; I almost always do. And that he’s right. But unless he’s one of us, how did he know?

‘Name’s Alphonse. What’s yours?’

‘Carol.’ It always helps me to say. Sometimes I go around saying it to people: I’m Carol. Try not to: the SW says.

‘You know what, Carol?’ he says. But not dirty intimate; it’s only the drink’s made him debonair. ‘Making like you have a neighbor? With the way you look like. Some guy who’s dangerous might think you have a pad. And want to crash.’

Why does honest advice make me see red? Maybe because I’ve had so much of it.

‘Maybe I do have one.’ But I’ve never said that, before. It’s a hard path I walk. You don’t have to walk it, the SW says. ‘I know’—I yelled at her last time—‘and that’s

my

disability.’ That shut her up.

He shakes his head, solemn. ‘The shoes are good. Even that skirt and blouse can pass these days, though you’ve buttoned wrong. Lipstick, even. Hair? Who knows a real mess nowadays from a fake one? And the bike, a touch of genius. I was fooled, first off.’ He shakes his head. Drunks do sermonize. ‘But not with those fingernails of yours. Like some cavewoman digging herself an exit.’

I like a sharp tongue. I have one myself, now and then. And his same eye for detail. ‘I have this nail downer. Sometimes I scrub till I bleed. Sometimes I let go, like this. On purpose.’ And not only with the nails. ‘But today, where I stash the bike, they stole my support gloves.’ That did happen, once.

This time his headshake admires me. ‘To crash with a bike. In a garage?’

Used to. When I was on the street. But couldn’t stand having to do a trick with that guard. ‘No one’s followed me yet, Alphonse.’ And no one will. Where I hang out, I’m normal. I’d kill—I tell the SW. She only smiles.

He’s slipping out the pint again.

‘I only spoke to you because winos aren’t dangerous.’

I mean to hit home but he only shrugs, wipes his mouth and stashes the bottle again. ‘Good old Tokay. I’d offer you. But now we’re telling I can see what you’re on. That prescription drug, isn’t it, Carol. The one makes a person shift from foot to foot. That’s rough.’

It is. Worst of all, that people can see. ‘Why’s it any rougher than you?’

‘They want me to stop what I’m on. People who say they care. Or the doc. But they won’t ever want you to, will they.’

That’s the burden of it. He’s put it sharp. Like the nurse when she twiddles the scale for you. Saying: why do I bother, I can see your bones. ‘I don’t go to the hospital anymore.’ I whisper it.

‘They can’t get me to go in,’ he says, proud.

‘Oh. Alphonse.’

‘Don’t read me the book, Carol.’

No. But he looks so good still, the head up, the mouth not loose yet, the shock of hair as thick as mine. Too good to waste yourself, boy—or girl—is what they tell you. They even wanted me back in school; they know better now. ‘How old are you?’

‘Didn’t want to say. After you did. Twenty-eight.’

He sees round my disability. I see round his. The wall stays the same.

‘See you,’ I say. ‘Gotta keep walking.’

‘Parting is sweet sorrow,’ he says. ‘But gotta keep to my task.’ He pats his hip where the pint is. ‘Bye.’

When I get back to the pad I do have, the SW is sitting on the stoop. She comes once every eight days, never drops in. Once last year, she did. Upstairs, I was just sitting there. But the time I’ve wasted, being checked up on; it all came up in my throat. ‘What are you, a lezzie, this extra snooping?’ I said. ‘You’re not eating, I knew it.’ she said. ‘You’re thin as a ghost.’ And she brings out a salami from her bag. But that was last year. I eat now. It’s part of my job.

So is this room-and-a-half, with a real cot in it. Up four flights, toilet, running water; renting in the barrio can still be a bargain if you don’t mind the Spanish screeching, day and night. The woman next door, Mrs. Lopez, scrubs her two front rooms like she does her kids’ necks; the grandmother in the back bedroom, her mother-in-law, won’t let her in to clean. The week I moved in, Carmen Lopez knocked on my door, bringing me a hospitality bowl: a lemon, an orange, half a papaya with the stone still in it, a can of coconut milk and a packet of Goya seasoning. We swap cockroach recipes; she started me on the sprinkling; now we do it together. Better than pushing them back and forth, she says. Bicarb-and-borax works best. When she caught her husband knocking at my door one night she came at him with one of her four-inch heels; his forehead has a dent. The women are the queens here; they build up the men to think they are the kings. Now when he carries my bike up the stairs for me she calls out—‘Whatta guy!’—first in Spanish, then in English so I will hear. Angel, her oldest, I have promised to let ride the bike when he is ten; he is oiling it. They keep winning me over, it’s hard not to be.

The SW, Mrs. Gold, wanted me to call her Daisy. ‘I’ll call you Gold,’ I said ‘—that’s professional.’ She has to call me Carol; that’s what her job tells her to do. I have to admit this helps. We both know that getting me to admit things is prime. Only I get so sick of what we both know.

‘I liked your hair blonder,’ I say fast, the minute I see her on the stoop this time. I have to get my oar in quick. Between us, I rate as the one on the fashion beat, but we won’t have any of that upstairs. As we climb, we both check. In my book, she’s tending to fade. My guess is the hubby was the one to leave. Once she brought her two kids along here, but it wasn’t a success. Divorce brats, with that special kind of ego. The Lopez kids have the charm. ‘You bring your kids on account of that crack I made,’ I said to Gold—meaning when I asked her was she lezzie, but she only laughs, which is better than when she sighs at me. I was a swinger once, but always with guys. Now I don’t do any of it. Maybe I did it to show I was vulnerable, she says; that’s her school of thought.

Upstairs I go quick to the sink and soap the nails, but she saw them when I fumbled the key; she isn’t fooled. ‘Okay, Gold, so let’s get to the Try-not-to’s,’ I say. ‘Open the fridge.’

It’s secondhand from the donation center, but works.

Tacked on the door there is a list of meals—each item with a check. When she first got me onto that, I used to draw up menus to shock: pigs’ knuckles with whipped egg-white, ice-cream with snow peas, but that was juvenile, and god-awful if I was honorable enough to eat them. Now the meals are so balanced they could spin on a dietitian’s nose. Inside, when she opens up, the milk carton smells sweet—and has a red ribbon on it to show the level. The eggs are pillowed in their grey paper-carton casket: I couldn’t resist sticking a tiny flag on it, American of course. There isn’t a single festering dish in the box.

Gold reaches in to flip the ribbon.

I say, ‘I couldn’t find a rubber band.’ We both giggle.

‘Oh, Carol. If you could only be casual.’

‘If I could, Gold, you wouldn’t be here.’

A sigh. ‘Still, wish my kids could see that squeaky-clean box.’

She’s always posing me and her kids against each other. That is something she doesn’t know and I’m not telling. ‘No you wouldn’t. Gold. Because I cheat. Last night was when I ate every old leftover in the box.’

‘At least you eat.’ She is moving the milk carton aside. And there are the medicines. One has a seductive nipple-shape. The other squats in its box like a poltergeist. They are a new trust.

She checks. Both are empty. ‘You took them all? And I mean—take.’

‘No throwaways. I remember what you said.’

‘What did I say?’ She is truly puzzled. Her own slogans, don’t they register with her anymore? I wrote what she said in ink inside the box where I stash the barette; have even been considering a decal of it over the toilet—and she can’t remember it?

‘To remember the pills, “you have to take the pills.”’

‘You have a mind like a steel trap, Carol. When you want to.’

‘Trap?’

She squinches her eyes. ‘So, what was the week like?’

‘Mrs. Lopez and I did the roaches. Twice.’

‘Good.’

‘But they all went downstairs, to the tenants below. Is that right?’

‘Carol. I am not answering anymore of your questions about the state of the world.’

‘Yeah. Maybe there’s some pill you could take. So you could answer.’

I’m serious. Since the state of the world has got me where I am, maybe everyone should be taking pills for it. You take pills like I do, you better believe there’s one for every situation.