Indian Captive (17 page)

Greatly comforted, she slept that night with the roaring of the waters in her ears. The next day she followed the women over rough and rugged hills to the Indian village, a half-day’s journey farther north. Molly was sorry to leave the gorge behind, but the low rolling hills of the Genesee Valley were beautiful too. Composed of bark long houses and log cabins, the village was much like Seneca Town, though larger. It lay near the mouth of Little Beard’s Creek, and it was called Genesee Town—Gen-ish-a-u, which in the Indian language signified a

Shining-Clear-or-Open-Place.

Upon arrival, Squirrel Woman and Shining Star turned Molly over at once to Earth “Woman, famous among, the Senecas for her skills in dealing with all forms of sickness. Silently, Earth Woman looked at the girl’s thin legs and arms, examined her scratched limbs and swollen feet. She saw that her toes were worn almost to the bone from the rubbing of sand which had collected in her moccasins while fording so many creeks. Slowly she shook her head. Then she scolded.

“Why did you not kill her and be done with it?” she cried. “It would have been more merciful. A wounded animal should be put out of its misery. Such a journey is only for a strong man to take—not a child and a pale-face at that! The daughters of Red Bird have shown little wisdom.” She paused, then added, “But I will do what I can.”

Rebuked by a woman older and wiser than they, the two sisters hung their heads and without reply, returned to their mother’s lodge.

Earth Woman took the girl to the river bank and there in a shallow place, gave her a thorough washing. Then back to her lodge she brought her and placed her in a bed. There, tired and ill, Molly was to lie for many days.

Earth Woman prided herself on being able to cure all manner of fevers, plagues and diseases. She knew the exact medicinal root or herb to perform the cure for each. She set to work at once. She steeped red oak and wild cherry bark and mixed it with dewberry root. This she gave to Molly to drink frequently and in it she had her soak her feet, at intervals, for days. When the girl did not improve, she tried various other decoctions, but nothing seemed to help. A troubled frown settled on the Indian woman’s placid face.

Days passed one after the other, but Molly took no notice. Sometimes she heard Earth Woman start out the door on her daily trip to the woods or saw her come back again, her arms filled with roots she had dug or leaves and herbs she had gathered. Listlessly she watched as the woman mixed her medicines, setting them to steep or boiling them over the fire. Listlessly she watched, but her mind took in little or nothing of what she saw. She never spoke or asked a question.

The lodge seemed always quiet as if the other families had no children full of life and action. Or, perhaps all the other families had moved away. Perhaps they had all gone on the long journey, too. Sometimes a little white dog, like the one in Seneca Town, came whining to Molly’s bedside. Sometimes Earth Woman was not herself at all. One moment she was Bear Woman, pointing out weeds on a corn hill. At another, she was Squirrel Woman, scolding and angry. Then she turned into a white woman, with full-gathered skirts of homespun and friendly eyes of blue. The white woman was always in a hurry, going away somewhere. And when she went, Earth Woman came back again.

Long hours passed when no one was there. The fire was out, the ashes were cold. Had they all gone away and left her? Had they set the broom against the door, a signal of their absence? Slowly Molly crawled out of her bed. Over the dirt floor she crept as far as the door. Then she forgot about the broom. She made up her mind she would go away from the Indians. She would find her way home again. But Earth Woman came, picked her up and carried her back to her bed.

One day Molly was surprised to find Little Turtle looking down at her. But it couldn’t be Little Turtle—he was far, far away in Seneca Town on the River Ohio. She brushed her eyes to make sure she was not dreaming. The dream grew more real when Shagbark appeared. Then she knew she was back in Seneca Town. The long journey was the dream. She had never taken it. It was only a dream about Fort Duquesne and the white people there. They had not wanted her at all. There was no place now to go but home.

It grew more and more difficult to tell what was real and what was a dream. Molly could not think things out, her head was so hot; and Earth Woman’s medicines were sharp on her tongue.

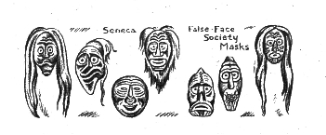

One day the air was suddenly filled with shouting, the beating of drums and the shaking of rattles. In through the lodge door rushed a number of queer-looking figures, their faces covered with grotesque masks, to represent woodland goblins or sprites. They plunged their bare hands into the fire, scattered the white ashes of the hearth and kindled a new fire.

It was like a queer nightmare to Molly. With a curious dream-like detachment, unmixed with fear, she saw one of the figures take ashes in his hands and sprinkle them on hers and Earth Woman’s heads. Filled with wonder she watched the figures prancing and dancing in the firelight and listened to the strange noises they made. When they left the lodge and all was quiet again, Earth Woman explained that the ceremony was a purification rite; that the False Face Company had put on masks to drive evil spirits from all the lodges in the village.

“The demons responsible for your sickness have been driven off,” said Earth Woman, confidently. “Soon now, your strength will return.”

Even Earth Woman’s words seemed part of the dream. Molly looked at her with glassy, feverish eyes and wondered what they meant. If only she would speak in English—then she might hope to understand.

Through everything, inside her mind only one thought remained clear—she must get away from the Indians. She must find her way home again. Only at home could she be happy. But each time she asked Earth Woman if she could go, she was told she was not strong enough; and so she waited.

Shining Star came sometimes and talked. Shining Star spoke of Red Bird and said she lived in Red Bird’s lodge. Was it true that Red Bird and Swift Water had made the long journey? Yes, Shining Star explained. It was true. And so had Little Turtle and the members of his mother’s family, as well as Shagbark. They had all come to the great Falling Waters and never meant to go back to Seneca Town again.

Then Molly understood why they had followed her to Genesee Town. They meant to keep her from going home. They were not her friends at all. They were Indians and meant to make her an Indian, too. But she would get away just the same.

One day Earth Woman sat by her bed, surrounded by dried corn-husks. The little white dog made a nest in them and slept. Earth Woman said that corn harvest on the Genesee was long over. All the ears in the great piles had been stripped down, the husks braided in bunches, about twenty ears in each. Now the fresh harvested corn hung high in the roofs of all the lodges, ready for winter use. From the scattering, loose husks left over, Earth Woman said that many useful things could be fashioned—moccasins, mats, masks, bowls and bottles. None of the husks would be wasted.

Earth Woman’s fingers flew fast and beneath them the dry husks made a gentle rustling. Molly watched to see what would emerge. A few moments later, the woman handed her a corn-husk doll.

Molly stared at it dully. “A corn-husk baby,” she said, slowly. “A baby made of corn-husks. But why has it no face?”

“If it had a face,” explained Earth Woman, “that would complete the effigy and invite a spirit to come and inhabit it. You could not tell the spirit was hiding inside, because the corn-husk is so unlike flesh. If you dropped the doll or hurt it in any way, you would be hurting the spirit. That we must never do—so we put no faces on our dolls.

“Besides,” Earth Woman went on, after a pause, “if it had a face with a set expression, the face would never change. With no face at all, the corn-husk baby can laugh, cry or sleep at will. Corn Tassel can see in its face whatever she wishes it to feel.” Under the woman’s strong fingers, the corn-husks began to rattle again.

Molly looked at the doll as it lay in the palm of her hand. It was not like a real baby at all, not like Blue Jay or baby Robert at home. It was like a miniature grown-up—a tiny, small-boned woman. Its arms were braided corn-husks, its clothes were strips of dried corn leaves. A handful of dried-up corn-silk was fastened to the corn-husk head.

She pressed it suddenly to her lips, then looked at it again. She was glad now it had no face—no dark brown eyes, no brown Indian skin, no shining black hair. She saw instead a fair white face with eyes of blue beneath the yellow corn-silk hair. A spirit

had

come to inhabit it. Her corn-husk baby was a white woman.

Then she thought of the white woman in shining silk at Fort Duquesne and her eyes filled with tears. “I see only sadness in its face,” she said.

“By and by the corn-husk baby will smile for you,” said the Indian woman. “She will smile to make you strong and well again.”

“Will I ever be well again?” asked Molly. She knew in that moment that there are two kinds of sickness—sickness of the heart as well as the body.

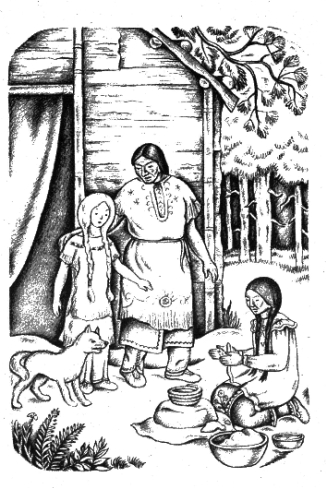

A day came when Earth Woman lifted Molly from her bed and led her out in the sun in front of the lodge. The little white dog came, too. Molly took a few uncertain steps and stared at what she saw.

An Indian girl sat on the ground beside a pile of wet, smooth clay. She was the same size as Molly, but very brown. She wore garments of bright-colored broadcloth, embroidered with beads. Two long black braids hung down beside her cheeks. She did not raise her eyes. She took wet clay between her palms and rolled it into a long; slender rope.

“What is she doing?” asked Molly, sitting down beside her.

“She is making a cooking-pot,” replied Earth Woman.

“What is her name?”

“Beaver Girl,” answered Earth Woman. “Well has she earned it. She is industrious like the beaver. She is always busy.”

Earth Woman sat down on the ground and began to pound a pile of rougher clay with sticks and after a time, knead it with her hands. Molly kept her eyes on Beaver Girl. Round and round she twisted the slender rope of clay in even coils upon a flat stone. Gradually each coil overlapped itself and the clay began to form the crude shape of a pot.

“Why does she not speak?” asked Molly.

“She is shy before the new white girl captive,” said Earth Woman, “but she is anxious to be your friend.”

“I saw no one make pots in Seneca Town by the River Ohio,” said Molly. “Do all the Indian girls here make cooking-pots?”

“Alas, no!” replied Earth Woman sadly. “Only Beaver Girl because I have taught her. Most of the women, even, have forgotten how. It is an old, old art, rapidly becoming lost. It is so easy now to buy brass kettles from the white traders. When I was young, we knew nothing of brass kettles. All the women made pots—beautiful pots to be proud of. As my grandmother taught me, so have I taught Beaver Girl.”

Earth Woman paused in her work to watch the coils build up under the Indian girl’s fingers. “So coils the forked-tongue,” she said softly, “whose bite is like the sting of bad arrows. So coils the rattle-snake, ready to spring; but if a man be wise, he will heed the snake’s loud warning. The sting of the forked-tongue is deep and the eyes of the heedless man will close in sleep, unless quickly he obtains help of our brother, the ash tree. A brew from the ash tree’s bark will check the poison; a poultice from its bruised leaves will heal the wound.”

Although Molly scarcely seemed to hear then, long afterwards the woman’s soft words were to come back to her, plainly, yet unmistakably.

Silently she watched Beaver Girl’s dark fingers work the clay coils together and smooth unevenness away. She saw her scrape the sides smooth with a piece of broken gourd. The shape of the pot grew more beautiful as she watched.