Indian Captive (9 page)

The village sat on the banks of the small creek, and bark canoes were lined up on the shore. It sprawled at the edge of the forest, for, like soldiers guarding, tall trees of maple, ash, poplar and beech loomed up behind. Between the village and the great river were fields of rich black earth, cleared of underbrush, all worked and ready for planting.

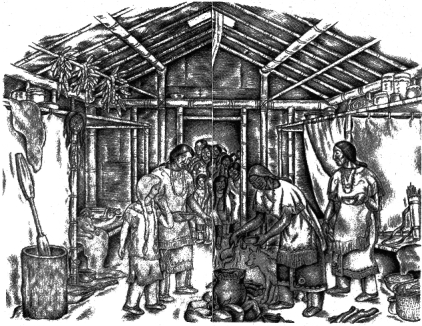

The Indian long houses were built on pole frameworks, with sides and roofs covered with great sheets of elm bark. Some were of great length, with rows of holes in the roof, from which streams of smoke poured forth. Here and there were smaller houses built of squared-up logs. All the buildings stood about haphazard around a central open space. Open platforms for storing hides and meat loomed up close by; and piles of firewood lay before the doorways. The whole scene had a bleak and cheerless aspect and Molly’s heart grew faint.

The two women came to a lodge at the edge of the village. Over the door hung the carved head of a deer, to show that all within belonged to the Deer clan.

The women pushed aside the deerskin flap and went in. Close at their heels followed Molly and at once the flap fell down behind her.

It was dark inside and for a moment she could not see. The room was filled with smoke, for the wind was blowing it down through the hole in the roof. Molly coughed and rubbed her smarting eyes.

Then she looked up and saw a woman, an older woman, poking at the fire, stirring it up to give it a better draught and make it burn more brightly. She saw that the fire was built in the middle of the floor and not in a fireplace. It was built on the hard dirt floor and the hole in the roof overhead was the chimney. She had never seen such a funny way of building a fire before and it almost made her laugh. No wonder the room was full of smoke! Had the Indians never heard of a chimney made out of sticks and mud?

The woman took a great wooden spoon with a curved handle and dipped something from an earthen pot that sat by the fire. With a broad smile on her face, she dipped it out all steaming and piping hot and put it in a dish. Molly stared as she did it. No, it was not a pewter dish, not a wooden trencher—it was a round-bottomed wooden bowl.

The smell of the food that was cooking made Molly feel suddenly faint. She remembered the piece of meat on the river voyage, but that was long ago. She pressed her hand on her stomach, to ease the pain of her hunger. Then, somehow, she was sitting on the floor—there were no stools to sit on, no benches even, no crooked puncheon boards. There was no place to sit but on the hard dirt floor, on a piece of skin stretched out.

The woman placed the bowl of food in Molly’s lap. Molly touched the side of it with her hand and comfortingly warm it felt. She picked up the wooden spoon and dipped it. What was it, corn or meat, or both? Slowly she sipped and slowly began to taste. She held the spoon in the air for a minute while she swallowed. Then carefully back in the bowl she placed it and did not lift it again. The food, whatever it was, was queer and tasteless. Was it only because her mother had not cooked it? Would nothing ever taste good again?

She set the bowl down on the ground at her side, hoping no one would notice. She must not hurt the woman’s feelings, the woman who had smiled so broadly while she filled up the bowl. Then Molly saw that the room was full of people and all were looking at her. But she could not eat. She covered her face with her hands.

The cross sister, whom she had not seen since they entered, snatched up the wooden bowl hastily, and as she did so, spilled its contents on the ground. Several dogs came running and quickly ate it up. Taking no notice, the older woman, who seemed to be the mother of the two sisters, went back to the pot and, smiling as before, filled another bowl to the brim. She handed it out to Molly, but Molly could only shake her head. She wasn’t hungry any more.

She looked at the other Indians standing about the room. She saw the kind sister talking to a tall, older man, perhaps her father. She saw women, two or three with babies strapped to their backs, and children crowding round. A young boy pushed out from behind, an Indian boy of eight or nine, about the size of Davy Wheelock. They all stared at her and though there were smiles on their faces, her heart began to beat in fear.

They talked in noisy tones and while they talked, she looked at the curious room. It was a long, open hallway, with gabled roof above and a double row of bunks lining the sides. The hallway was divided into compartments and a fire was burning in the middle of the floor of each. Did all the crowding people live in the rooms beyond? Molly looked at the bunks on the sides—the lower but two feet off the floor, the upper high under the roof. Bark barrels stood on the upper platforms and hanging about were bundles of herbs, dried pumpkins and squashes and hanks of dried tobacco. But, most important of all, Molly saw endless rows of corn hung along the roof-poles above—long rows of pale yellow corn braided together and hung up to dry. Up there, under the darkened roof, the corn glowed like warm sunshine, and she could not help but remember. Along the beams at home, above the fireplace, Pa hung his corn to dry. Oh, would she ever again help him to hang it there?

The crowding people talked in noisy tones. Molly wondered if the words could possibly have meaning or were only a mixed-up jumble of queer sounds. The people stared at her and kept on talking. They pointed to her hair and sometimes touched it with their hands. Then, after a while they seemed to forget she was there, but still they kept on talking. The noise grew fainter as if it came from far away. At last, Molly forgot where she was as, worn out with fatigue, she lost herself in sleep.

Sometime later, half-awake, she realized that she was being carried. For a moment, she felt her father’s strong arms about her, lifting her up to his shoulder and carrying her into the house. Then she saw it was not her father. It was the old Indian, Shagbark, carrying her over the mountain on the journey that had no end. No—she rubbed her eyes again—it was neither. She was not at home, she was not on the mountain. She was in an Indian lodge for the first time in her life.

The Indian woman, the woman with the kind and beautiful face, had picked her up from the ground and was lifting her into a bunk. The brown eyes looked down at her tenderly as she smoothed the bed and covered her up. Tired, oh, so tired, Molly gave one grateful glance, then closed her eyes and under the soft, soft deerskins, fell fast asleep.

Lost in Sorrow

M

OLLY WAS SITTING BESIDE

her mother. They were spinning flax together and the whirring of their wheels made a gentle, pleasant hum. Molly was to have a new gown as soon as the cloth was woven, a new summer gown of soft, cool linen. Her mother had promised to color it yellow with the bark of sassafras.

Ka-doom! Ka-doom! Ka-doom!

The sound of heavy blows repeated in quick succession came to Molly’s ears. She rubbed her eyes and turned over. She drew the covers close under her chin and slept again. Pa said the new gown should match the color of her hair…

The booming sounds broke through her sleep. She lifted her head and listened. Then she remembered. It was only a dream. Molly would never sit at her mother’s side and spin again. She would never wear a linen gown colored yellow with the bark of sassafras, colored yellow to match her hair. She was in an Indian bed; she had slept in an Indian lodge. She turned her face to the wall and cried.

Ka-doom! Ka-doom!

What was the dreadful noise? Why did it never stop? What were the Indians going to do? She wondered if morning had come.

Molly looked about her. There was little light to see by, for the bed was closed in on all sides. At the edge hung long curtains of buffalo robe. At head and foot were slab bark walls. Overhead, she could touch the bottom of the upper platform which was made of slats laced together. Molly’s eyes grew accustomed to the darkness. On shelves across the foot wall and hanging over her head she saw a curious lot of things—quilled bark boxes, piles arid bundles of valuables and clothing. The bed had belonged to some Indian before her.

The booming noise went on and the girl became more and more frightened. Then she heard a sniffling sound and felt a movement at her side. The curtains stirred. Was some one coming to wake her up? Would a brown hand push in rudely and take her by the shoulder? She was ready to scream…No—it was only a small white dog. He poked a cold nose to her face. He jumped up and licked her cheek. Was he, too, hungry for affection? Molly put her arm about his neck, as he snuggled down beside her. He was one of the dogs who had eaten her supper last night. She was glad she gave it to him—he seemed to like it so much.

The booming noise went on, but nothing seemed to happen. What were the Indians doing? Molly pushed a corner of the curtain aside and peeped out. The bunks across the room seemed empty, but in one someone was still sleeping. Someone was sleeping under a heap of skins and blankets, with the deerskin curtain pushed back. On the wall above hung bows and arrows, tomahawks, war clubs, pipes for tobacco, belts and pouches. It must be the woman’s husband. Was that where he kept his things?

Molly looked up through the hole in the roof and saw a patch of blue sky that told her it was morning. Her eyes followed the light as it streaked down through the dim interior. It fell on the bent figure of an Indian man. He was on his knees, brushing away the ashes, preparing to lay a fire. Carefully with his hands he scooped out a pile of earth, making a hole in the middle of the circle of stones. Over the hole he laid thin, dry twigs, arranging them in neat order.

Then he picked up a fire-drill and rested the lower point of the shaft upon a block of dry wood. He pulled the bow against the drill several times and got a spark started. He blew it to a flame and fed it with thin strips of bark. In a moment the fire was ablaze and, after adding some larger sticks, the man went into the adjoining room.

Molly saw the Indian woman come in—the older woman of the night before—with a load of wood upon her back. She put the wood on the ground and fed the fire as it burned more brightly. She brought water and poured it into the large earthen pot which sat on the stones at one side.

Molly looked down along the length of the bark house. The other families were stirring, too. Other fires were being made and children and grown-ups were turn-bling out of their bunks. Molly shrank back into her corner, not daring to move or speak, not knowing what to do. How could she get up and be one with this Indian family? How could she eat their uninviting food? How could she talk when she knew not a word of their language? How could she bear the rude stares of all the people? How could she live in a place where everything was strange?

Suddenly the Indian woman gave a call and threw a handful of bones to the ground. The dog that was so friendly leaped from Molly’s arms and jumped down. He ran to the woman and eagerly snapped at the bones.

The woman turned to the bunk. Her sharp eyes had seen the dog jump out. She saw Molly’s scared face peeping, so she came over and pushed the curtain back. Without a smile or a word she beckoned the girl to get up.

Slowly Molly obeyed. She put her feet to the ground and drew on her moccasins. She stepped out from behind the curtains ready-dressed, wearing the Indian clothing they had put on her the day before. The woman threw the curtain onto the upper platform and spread the deerskin coverings out to air. With scared eyes Molly watched her, not knowing what to do. Uncertainly she stood, shifting from one foot to the other.