Indigo (8 page)

Authors: Clemens J. Setz

Any topic of conversation but this monster in his head, growing by a certain amount every day, every hour, was for his uncle uninteresting to a grotesque degree.

Yet he himself seemed not at all to suffer from the presence of the number-parasite the way those around him (who longed for ordinary communication with him) did, he maintained and cultivated the number like a flower bed. He had cared for it from infancy, through the very early stage of 5, 6, 7, then through the rapidly developing two-digit and three-digit, and finally even through the adolescent four-digit range, which it had also soon left behind. It could be claimed that the number was now gradually nearing mature adulthood. Every evening he entered it in a small notebook, which was meant only as a sort of summary of the day's events, not as a memory aid. For he never forgot the number itself, not even after seventeen hours of sleep under the influence of strong sedatives. It stayed in him.

Sometimes, when the number had an unremarkable phase ahead of it, the day would be a good one, then you could go for a walk with him or treat him to an ice cream in the quiet café just after the entrance to the clinic. He would sit on one of the plastic chairs, would be responsive and calm and even capable of making a joke. You could get along with him. Now and then you could tell from a silent nod that he had again added 1 and was now taking in the taste and the shape of the new number. If he licked his lips, you could assume that he was satisfied with it. But even if the number wasn't all he had hoped, he was never mad at the new number for that, it couldn't help its appearance or its behavior, it had just hatched, after all, and needed attention, just like any other number. Who knows, maybe it would ultimately reveal a few nice divisibility properties, hidden talents that had escaped him at first glance.

The fact that the number kept growing didn't bother him, for it went nicely step by step, he explained. Sure, if he suddenly added a three-digit number and so skipped hundreds of other stages of the number's development, then that would certainly throw some things off. That would be like starting a car in a too-high gear. But the way it was going now, each day about fifty steps, that was manageable, that didn't demand all too much of you. For he was quite well aware of the danger emanating from such a companion number. How easily people with less robust nerves than his might suspect in the numerical sequence a secret code or a message from the beyond or from other realms of heaven. It was perfectly clear to him that the number was only a number, no more and no less. He looked after it and dealt with it responsibly. He had never made a mistake, taken a counting step twice or reversed two digits within the number, no, the number was completely safe with him. Nothing could happen to it, even if some people claimed it would one day be taken away from him. He knew that this was not even possible, was in fact a contradiction in terms. In any case, he would continue to fulfill his care obligations toward this precious and vulnerable being, for he, Johann Rauber, was simply the only protector the number had in the whole world. Impossible to imagine what might happen to it without him.

Robert sat on a bench in front of the psychiatric clinic at the University Hospital of Graz. There was always something off about psychiatric institutions, that is, in architectural terms. Either they were as large and labyrinthine as a courthouse, or the architect had taken the metaphor of illness literally and applied it to the roof structure, or they were intimidating in the way the doors sprang open of their own accord, or they were, like this building here, hidden in the woods. All the other clinics could be reached by climbing a few steps from the final stop of tram line 7; from that point on everything was logical, even the signs made sense. Not so the psychiatric clinic. You had to walk down a dark and accursed path through the woods, and you then came upon a building in which you could not for the life of you imagine mentally ill people getting better. The view from the window every evening alone! All night long the trees talked about you with rustling gestures and read your thoughts.

At least here, just next to the parking lot, a beautiful, quiet tree grew, which seemed not to belong to the small patch of woods. Like an opera singer in front of the chorus it stood there, in the endlessly complex contortion that makes up a tree. Why did trees look like that anyway? They grew according to a simple principle, after all, straight line, divide, two straight lines, divide, four straight lines, and so on, where did those crazy angles come from? Possibly water veins, magnetic fields, or sunlight played a role. Or maybe, thought Robert, a tree was just terribly sentimental. Recently he had with some abhorrence looked at the famous picture by the photographer David Perlmann in an art magazine showing a tree in Pennsylvania that had, as it were, embraced a white single-family house from the side with its branches. First the branches had grown through the perpetually open kitchen window, then they had leaned up against the house's south wall, finally it had been the roof's turn. Within thirty years, in which a married couple had grown old in the house and hadn't bothered with anything that happened outside, the tree had merged with the house. The family that lived in it now had the burdensome tree, a danger to the stability of the roof, which had been built with very light materials, photographed before having it removed. There had, as the magazine reported, even been a sort of competition. David Perlmann's picture had won first prize, because the tree looked so sure of itself in it. And maybe that was the problem, thought Robert. A tree always wanted to embrace everything. It stands in the same spot for a hundred years and is overwhelmed every day by its affection for a few ducks in a pond, an intertwined couple on a park bench, a delightful, colorfully overflowing garbage can, or a mysteriously curved park lamp. When one of the creatures or things attracts its attention and the desire to embrace it becomes irresistible, the tree beginsâslowly, of course, terribly slowlyâto grow in its direction and to stretch out its branches toward it like arms. It's like in those well-known speed dreams, in which you can't move precisely when you're desperate to. If you give up, however, you sometimes even fly awayâinto the sky, always in the wrong direction. And the tree, as a result of its many minimal daily, hourly changes of direction in its growth over the years, has turned into a bizarrely distorted form.

Stupid tree.

And stupid clinic. One morning in it, and he was thinking completely retarded nonsense.

Stupid tree, suck a Frisbee, motherfucker!

To bring himself back down to earth, Robert recited a few forbidden, radioactive words:

filthy cunt

,

Jewish pig

,

degenerate

,

nigger

. Then he stood up.

No, these long hours with Cordula did him no good. He constantly had strange thoughts, as if they were being put in his head by a different, older brain, he felt remote-controlled. No wonder. And his clothing was always soaked in sweat, even though it was only seventy-two degrees. As after a sweat bath in the wretched yard at Helianau. The disgusting feeling of being the only one they could do it to. Because his I-space, his zone, his region went through those lunar phases in late puberty, waxing and waning, then even vanishing completely. What vileness.

And today, on this late summer day in 2021, after he had put away his freshly painted monkey portrait, he was very grateful to Cordula that it hadn't been a bad attack this time. She was sleeping. She was breathing normally. She was well adjusted.

[RED-CHECKERED FOLDER]

THE HALDRESS OF BONNDORF

I

N THE YEAR 1811

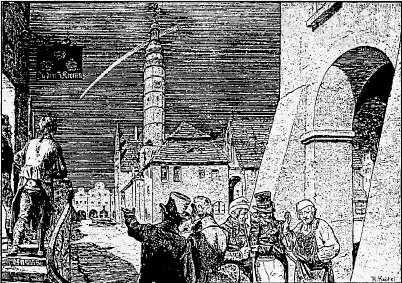

there lived in the city of Bonndorf, in the Danube District, a haldress named Beglau. She took great joy in her baby, to whom she had given birth a few weeks earlier. But then came the comet, which in autumn visited the sky over the earth and of which the kind reader has elsewhere heard.

During a midday meal at the Wounded Landlord Inn, the Family Friend was told that after the appearance of the comet in the vicinity of the moon a change had occurred with the haldress in Bonndorf. While the comet, like a holy evening prayer or like a priest when he roams the church and sprinkles the holy water, like a noble good friend of the earth who has a great longing for her, like a mischievously winking eye in the night firmament, remained there, people at times felt as if it wanted to say: I was once an earth too, like you, full of snowstorms and thunderclouds, full of hospitals and Rumfordian soup kitchens and churchyards. But my Judgment Day is over and has transfigured me into heavenly clarity, and I would like to come down to you, but I do not dare, because of the oath I have sworn, lest I become impure again from the blood of your battlefields. It had not said this, but it seemed so, for the closer it came, the more beautifully and brightly, joyfully and fondly it shone, and when it receded after a certain period of time measured in accordance with celestial principles, it became pale and gloomy, as if it were itself grieving deeply. The haldress Beglau in Bonndorf must have looked up at it often when she crossed the wellbridge in the evening on her way home, where her baby waited for her. The baby was still quite small, a little lump of living tissue in a cradle next to the stove. The more she stayed outside in the comet nights, as her occupation required, the odder the broad fluttering belt of the Milky Way and the other cosmic curio sets of the stargazers appeared to her. Like jugs and pots in a cupboard, those things up there seemed to her disorderly, and she had all sorts of fantasies, so that she soon acquired a rather strange reputation in the area. Meanwhile, she began to fear her own baby. The people of Bonndorf heard about that too, and they sent the doctor to her, who examined her. Unable to find any causal change in her vessels, he took a look at the baby in the cradle. He was a fine boy, wrapped in clean white linen. And as the doctor now looked at the child, he was beset by a terrible headache, followed by pains in his body and a malaise of the soul more intense than anything he had experienced since his boyhood on a strict and bleak abbey estate. The haldress, meanwhile, complained of exactly the same ailments, and together they only barely made it out to the well and leaned there against its stone. Having recovered his breath, the doctor realized that his usual strength had returned.

The baby was subsequently named the

Comet Child

and grew up among caring nuns in a separate area.

Remember: It is fortunate that in certain cases we do not first send for the priest but instead for the doctor. Thus was the city of Bonndorf saved in the year of the comet 1811 from an arrival of the devil incarnate.

(

FROM

: Johann Peter Hebel,

The Calendar Stories: Complete Tales from the Rhineland Family Friend

, p. 334-335)

5.

In the Zone: Part 1

B

Y

C

LEMENS

J. S

ETZ

*

Pension Tachler in Gillingen

Gillingen is a typical southern Styrian small town in the middle of hilly wine country and with a world-famous cable car, which is also touted as a tourist attraction by the neighboring town of Seelwand. It's part of those foothills thatâas Elfriede Jelinek writes in her masterpiece

The Children of the Deadâ

the mountain stuffs in its pants pockets.

When I arrived in Gillingen by train, pleasantly broken clouds hung in the evening sky over the town, the famous gondolas of the cable car hovered in the distance over the western slope of the mountain, and in the covered waiting area of the small train station I noticed to my great delight a man pushing an old-fashioned high-wheel bicycle out into the sun. I loitered a bit longer in front of the train station because I wanted to see the man climb onto his high-wheel bicycle and ride away on it. But he did nothing, he seemed to be waiting for something, looked at his watch, turned in all wind directions and stared. After about ten minutes I left in disappointment.

On the way to the hotel I called my girlfriend, Julia. She listened to my description and afterward asked whether the man had had a mustache. I said yes, even though I wasn't at all sure. Then we agreed that men with high-wheel bicycles must absolutely always have a mustache, and ended the conversation. I had almost reached Pension Tachler anyway.

The large building with the vacancy sign under the gable was in the immediate vicinity of a spacious tavern named Ernst'l. Written with chalk on a blackboard on the sidewalk was today's lunch menu: Pork schnitzel with fresh potatoes; ½ a fried chicken; boiled beef with sauerkraut.

The pension itself made a pleasant impression. Next to reception a large bird with a strikingly long beak perched in an open cage. A young woman sat in front of a computer and looked up.

â Good evening.

â Hello, I said. Clemens Setz. I reserved a room for two nights.

â Aha, yes . . . let me see . . . Yes, here.

She had found the entry on the calendar.

â Have you ever stayed with us before? she asked.