Insectopedia (58 page)

Inspired, he spent five months studying the natural history of the swallowtail butterflies near his home. Just a short time before, a train full of students had been massacred on this spot by a U.S. plane. Often, he just sat and stared at the animals fluttering over the scene, immobilized by their life force and beauty, just as he was by the dragonfly in the bomb crater during the war. Looking back now, he sees his immersion in the swallowtails as the therapeutic compulsion that released him from the weight of the war and its afterlife.

Perhaps, as it does me, this story makes you think of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, Li Shijun, Joris Hoefnagel, Karl von Frisch, Martin Landauer,

Jean-Henri Fabre himself, and of other people for whom an insect universe provided an often-unexpected refuge. Perhaps it brings to mind people who, to put it another way, entered the world of insects and were, in turn, entered by it, who at times were swallowed up by it and who at other times found their bearings inside it, such that the normal scale of existence—the standard hierarchies of being—in which we know small things because they are physically smaller than we are and we know lesser things because they lack our capacities, was no longer a basis for either action or meaning, and such that the enormity of the circumstances that bound their lives could assume another proportion and a different place in their world, such that the world itself could become immeasurably larger and unconfining.

At some point during the solitary months spent observing swallowtails, Yajima Minoru made the decision to dedicate his life to studying insects. It was almost sixty years later when CJ and I met him for lunch in a cafeteria in the Tocho, Tokyo’s monumental two-towered city hall. By then he was one of Japan’s most eminent biologists, the creator of the world’s first butterfly houses, a maker of popular nature films, a leading conservationist, the pioneering developer of numerous insect-breeding protocols, and a science educator committed especially to sharing his love of insects with children. He was full of energy, telling us eagerly about his newest project, Gunma Insect World, which includes a spectacular butterfly house (designed by the architect Tadao Ando) and a substantial area of community-restored

satoyama.

It was due to open the next day, and we were all disappointed that CJ and I wouldn’t have time to visit. Yajima-san was kind, unassuming, generous with his time, and infectiously positive. We talked for a long while and afterward posed for photographs, tiny as ants in front of the colossal municipal building.

The destruction of Tokyo was also the destruction of a thriving commercial insect culture centered in the city. “We were back to the beginning,” wrote the historian Konishi Masayasu, referring to the

mushi-uri

, itinerant

sellers of singing insects who had first appeared in Osaka and Edo (Tokyo) in the late seventeenth century and who reappeared after the war to hawk their cages in the ruins of the capital.

21

It’s not difficult to imagine the special importance at that moment of these animals, with their bittersweet songs of melancholy and transience, their cultural intimacy, and their unconditional companionship. But the

mushi-uri

were not walking the streets by choice. The bombings had destroyed Tokyo’s insect stores, and although the traders soon managed to set up roadside stalls in the Ginza shopping district, even then they were still back at the beginning: their breeding infrastructure had collapsed, and like the original

mushi-uri

, the postwar traders were simply selling animals they trapped in the fields.

Japanese insect traders had known how to breed

suzumushi

(bell crickets) and other popular insects by the late eighteenth century. They had also discovered that by raising larvae in earthenware pots, they could accelerate the insects’ development cycle and increase the supply of salable singers, inventing techniques that are still in use today (among cricket breeders in Shanghai, for instance). Konishi describes a florescence of insect culture under the Tokugawa shogunate, that long period of relative isolation, from 1603 to 1867, when the possibility of external travel for Japanese people was strictly limited and the only point of entry for foreigners was through the port of Nagasaki. He notes the existence of clubs for the study of animals and plants in Nagoya, Toyama, and elsewhere; he describes the biennial residence in Edo of the daimyo, the feudal lords, during which the notables and their intellectual allies spent their leisure time collecting, identifying, and classifying insects; and he discusses the long-standing scholarly interest in and gradual incorporation of

honzo

, Chinese materia medica, a healing corpus that includes not just plants and minerals but insects and other animals.

22

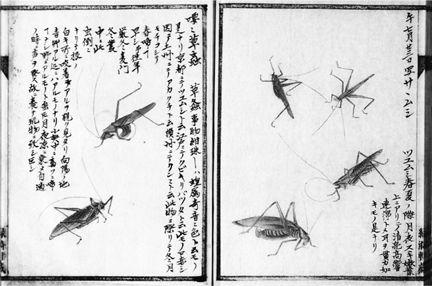

Rather than making specimens in the manner of the European naturalists, these insect lovers, the

mushi-fu

, preserved their collections in paintings annotated with observations, dates, and locations. Prominent artists such as Maruyama Okyo (1733–95), Morishima Churyo (1754–1810), and Kurimoto Tanshu (1756–1834), whose

Senchufu

is one of the incomparable treasures of the period, painted from life to produce portraits of insects and other creatures that not only were outstanding in their delicacy and

precision but also were organized serially in a way that prefigured the arrangement of the

zukan

guides used by insect collectors today.

Konishi calls the Tokugawa shogunate the “larval stage” of Japanese insect studies. Despite their commitment and ingenuity, without sustained interaction with Western naturalists the

mushi-fu

were merely incubating their passion, he says, awaiting the external stimulus that would trigger its transformation. To Konishi, it was only through the energy unleashed in the Meiji period (1868–1912), with its eager embrace and importation of Western knowledge, that Japanese insect love entered the modern world and found its adult form. That moment of modernity can be dated to 1897 and the response of the Meiji government to the invasion of the national rice harvest by

unka

leafhoppers. In Japan, as in Europe and North America, entomology—the study of insects according to Western scientific principles—was tied from the beginning to pest control and the management of human and agricultural health.

This journey from enthusiasm to entomology is a standard narrative of Japanese science and technology, late on the scene but quick to play catch-up. As an account of a passage from darkness to light it closely parallels the conventional narrative of the scientific revolution in Enlightenment

Europe two centuries earlier. But as many scholars have pointed out, these histories not only rather take for granted the Enlightenment/ Meiji belief in the superiority of science over other forms of knowledge but also assume too easily the distinction between them, underestimating the continuities that tie earlier ways of understanding nature to those that come to count as modern, and overlooking the fact that enthusiasms and instrumentalities persist together side by side and often without contradiction or conflict, in the same pet store, in the same magazine, in the same laboratory, even in the same person.

23

On the other hand, there’s little doubt about the surge of energy in Meiji Japan that resulted in insect love being recast in entomological terms and supported by an array of institutional innovations. Konishi describes the “fever” for beetles and butterflies that took hold among biology students at the newly formed Tokyo University (1877); the groundbreaking publication of

Saichu shinam

(1883), a handbook of advice on collecting, preserving specimens, and breeding (drawn largely from Western sources) by Tanaka Yoshio, the founder of Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo; and the opening of three stores in Yokohama selling Okinawan and Taiwanese butterflies to sailors and other foreign visitors.

Half a century later, the descendants of the first patrons of those butterfly stores would bomb the emergent industry back to its eighteenth-century beginnings. Somehow, Japanese insect culture recovered with the same alacrity that had allowed it to seize upon Western science in the years following the Meiji Restoration. Somehow, the survivors of the destruction of 1945 drew strength from trauma. Yajima-san meditates on the life force of the dragonfly laying her eggs in the flooded bomb crater. Shiga Usuke, the founder of the country’s most eminent insect store, describes how he buried his precious supply of specimen pins in one of those shallow Tokyo bomb shelters and how, returning after the war to find them rusted and useless, set about designing more durable equipment, succeeding many years later in manufacturing instruments from stainless steel.

Shiga Usuke was born in 1903 into a family of landless peasants in the mountains of Niigata Prefecture, northwest of Tokyo.

24

Like Yajima Minoru, he was a sickly child who spent much of his time confined to his home—in Shiga’s case because of malnutrition. When he was five, he went blind after a simple cold turned into a fever. Each week, his father carried him three and a half miles to the nearest doctor. Eventually, Shiga-san regained the vision in his right eye but not in his left.

Despite his poor health and having to work to help his family, Shiga-san was an outstanding student and, as a result, was sent to Tokyo for high school. Unlike the insect men whom CJ and I encountered, he was never a

konchu-shonen.

In fact, he writes, he had little awareness of his environment and no memory of ever hunting insects as a child. He explains this as an effect of poverty and sickness and his preoccupation with work, but quickly interjects a doubt: are these simply excuses for the insensitivity he once had to nature, an insensitivity, he adds, that was normal among those around him?

High school was uneventful. He worked in his headmaster’s household and graduated at fifteen. It was then that he found a position at the Hirayama Insect Specimen Store in Tokyo, one of only a very few businesses in the city that made specimens for collectors.

Hirayama employed two workers. One was assigned to the store and one to the household. Shiga-san was the household servant, tasked with cooking, shopping, and cleaning. Despite this, he soon began to take notice of the store’s collection. Surrounded by insects, he started to see things he’d never seen before. He looked closely and observed differences, details of color, shape, and texture. He found himself looking more carefully, finding the specimens more interesting, excited by their unexpected beauty. Very quickly he determined to make a life as an insect professional. Soon he was bribing the store apprentice with candies to show him how to collect—at that time, houses in the city were surrounded by green space, and it was easy to find insects—and how to prepare specimens. But even as he became fascinated by all the variety, it

also overwhelmed him. How could he ever hope to master this field? Hirayama carried no books or good-quality

zukan

in which to explore, and the store owner had no interest in furthering Shiga’s ambitions. Thrown back on his own resources, he stole time to study the shop’s collection, memorizing the names of species and matching them with the number and patterns of wing spots and the size and shapes of the markings.

Among Hirayama’s insects, he was in a dreamworld. Seen through a hand lens, every specimen was astounding, especially the butterflies. But back in the world of men, things were different. People were constantly reproaching him: why did he waste his time on this dross? Their contempt was intimidating and oppressive. Even his father—an open-minded man who supported his impoverished family by fixing umbrellas, making balloons, giving massages and acupuncture, and telling fortunes, and who was gaining a reputation as a midwife (an occupation forbidden to men)—was hostile to his work. People judged insects only according to whether they were useful or dangerous. It was acceptable to eliminate them but not to collect them. Away from Hirayama, Shiga-san remembers, he felt that he, too, was just a

mushi.