Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (6 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Whatever their divine origins, these visions were of changes that most Indians, familiar with the disruptive, enervating effects of liquor, could accept, at least for a while, and their will to fight was only reinforced by ham-fisted British negotiating tactics. Soon the tribes were on the attack in many places. Every British outpost west of Detroit, all the way to Green Bay on the western shore of Lake Michigan, fell to the Indians. Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Niagara were in effect besieged as Amherst’s road network was cut in countless places by raiding parties. In short, Pontiac conducted the very sort of campaign that Rogers had envisioned from the outset of the French and Indian War—coordinated, protracted, widespread raiding by small bands of highly mobile fighters.

Faced with these reverses and an almost entirely irregular enemy campaign, Amherst had to perform a kind of strategic triage. He focused on the idea of helping his three major forts withstand Indian sieges, and wrote to one of his subordinates about the need to employ any and all means at hand, including allowing blankets that had been used by smallpox victims to fall into enemy hands. In addition to waging a primitive form of biological warfare, Amherst also called for extreme brutality, including mass executions of warriors and their families.

15

But at this point in the war he had little ability to defeat the Indians in battle. The best he could hope for was to send relief columns and convoys to his besieged forces. Robert Rogers and his rangers joined one such force, heading off to Detroit in the fall of 1763. Unfortunately the British commander of the expedition, James Dalyell, a man of high birth but of low capabilities, disregarded Rogers’s advice and sent his massed force out to “hunt down” the Indians. The result was a predictable disaster. The British commander was killed and decapitated, and his head shown around triumphantly. Rogers fought heroically and fell back into Detroit with the other survivors of the rescue column. The fort held until further relief, under more prudent command, arrived.

Soon the British began to restore the equilibrium in the irregular fighting and were able to bring Pontiac to the peace table with offers of a renewed flow of goods and the implicit threat to unleash upon his people and his allies a terrorist swarm of Shawnees who were not members of the pan-Indian movement. Pontiac agreed to treaty terms. But the promised goods soon stopped coming, and the great chief was murdered by a disgruntled warrior from his own tribe. Without his vision and leadership, the Indians never again achieved meaningful levels of unity.

For his part, Rogers went to Britain to request permission to conduct explorations aimed at finding a route to the Pacific—the fabled Northwest Passage. His petition was denied, but he was given a command in the Great Lakes region that he used as a jumping-off point for extensive forays, including some that extended far beyond Crown territory. His detractors—and they were many—helped raise a charge of treason against him, which he successfully defended.

This experience seems to have soured him on British rule, and at the outset of the Revolution in 1775 Rogers sought service with the rebels. Given both his character flaws and his long service to the Crown, many among the revolutionaries worried he might be a British spy. Those suspicious of him included even George Washington who, in a letter to Congress, gave voice to his concerns about the loyalty of the great ranger. Although Washington made no direct charge, he referred quite insinuatingly to “the Major’s reputation, and his being a half-pay officer.”

16

This was enough for Rogers to be blackballed by the rebels, and he soon shifted his support back to George III.

Rogers quickly helped form and command units of “the King’s American rangers,” who fought with considerable skill and a desperate fury across much of the same ground Rogers and his rangers had traversed in the war against the French and their Indian allies. He remained a careful recruiter, at one point even catching the rebel spy Nathan Hale, who sought to infiltrate the force and report on British intentions.

17

Ironically, many of the Native Americans whom Rogers had fought in the previous war now allied themselves with the British against the rebels. They added significantly to the Crown’s bush-fighting capabilities, the end result being the rise of an irregular war out of Niagara that for its ferocity made Pontiac’s campaign seem pale by comparison. Indeed, the most savage battle of the Revolution was fought with irregular troops on both sides in 1777 at Oriskany, which featured perhaps the war’s highest percentages of each side’s forces killed or wounded in action.

18

Rogers eventually alienated his British masters—who had become more enamored of another Tory ranger, one Walter Butler—and left their service while the war was still going on. He returned to the United Kingdom drunk, divorced, and despondent, dying there in 1795. The British erected no great monument to him, nor of course did the Americans. But the ultimate success of the Revolution had nonetheless been critically dependent upon Rogers’s influence. He may have fought against his own people, but the troops who defeated the Redcoats and loyalist Tories grew from the earlier seeds he had planted. As one thoughtful account observes, “all the original rifle units of the Continental Army could be lumped into the ranger class.”

19

These troops held their own in stand-up fights, fended off the irregulars they had to confront, and in the decisive southern campaign, blended traditional battles and insurgent actions in a manner and under a leader, Nathanael Greene, that the British could never effectively counter. For having inspired and helped enable such an innovative approach to war, Robert Rogers deserves an honored place in our memory—if not our sympathy.

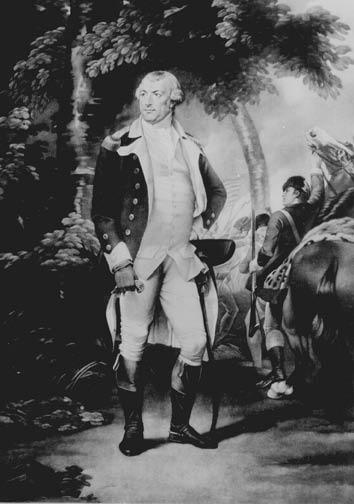

FIGHTING QUAKER:

NATHANAEL GREENE

Painting by C. W. Peale, U.S. National Archives website

In one of military history’s more ironic turns, each side began the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) with considerable capacities for waging irregular warfare, yet both proved oddly reluctant to emphasize this mode of conflict. For their part, the Americans started with a citizen soldiery whose ranks were replete with fine marksmen who also had a great aptitude for operating in the wilderness. Their superiority in firefights, when allowed to aim freely at marks of their own choosing, was apparent in the early engagements in and around Boston and would surface time and again throughout the war. But for some reason rebel leaders from the outset chose to transform these fine natural soldiers into a “proper” (i.e., European-style) conventional army designed along classical lines, closely drilled in ordered movement and massed volley fire. The principal champion of “conventionalizing” the Continental Army, oddly enough, was George Washington, whose early experience with Braddock was apparently not searing enough to tarnish his dream of building a force that looked smart on the parade ground and fought well on the traditional battleground. As a supreme commander he proved quite hidebound about military doctrine.

Nevertheless Washington enjoyed the full confidence of Revolutionary political leaders and, save for the brief, futile plotting of the “Conway cabal,” which sought to have him sacked, he was able to have his way. The military historian Russell Weigley has thus observed Washington’s position in the early strategic debate with Charles Lee—not one of the Lees of Virginia, but a retired British officer with rebel leanings who had also served under Braddock—about how to wage the war:

Washington rejected the counsel of Major General Charles Lee, who believed that a war fought to attain revolutionary purposes ought to be waged in a revolutionary manner, calling on an armed populace to rise in what a later generation would call guerrilla war. Washington eschewed the way of the guerrilla.

1

Soon drillmasters like the imported Baron von Steuben were teaching soldiers to march, shoot, and die like automatons. This accorded closely with Washington’s wishes, and the baron’s influence rose all the way to the top of the rebel military as he brought to bear his insights from service as a staff officer to Frederick the Great of Prussia.

For their part, the Redcoats also had significant potential for conducting irregular warfare at the outset of the Revolution. Every unit had riflemen and flankers, and all held out the promise of making further tactical improvements over time, building upon the progress that they had made in the previous war. In addition, Britain’s allies among the native tribes and the large number of American colonists who remained loyal to the Crown—the Tories, nearly a third of the total population—provided powerful augmentation in the tactic of bush fighting. Yet when given the opportunity to fight in a far more traditional manner—on open ground cleared for agriculture—the British too came to lean far more heavily toward the conventional.

Results in the field soon reflected the traditional cast of the contending armies, and not favorably for the rebels. George Washington’s attempts to stand fast and fight on Long Island in 1776 nearly caused the loss of his entire army. Another near disaster was barely averted the following year in the vicinity of Philadelphia. To be sure, there were victories as well, in a surprise attack by a small detachment on Trenton the day after Christmas 1776, and at Saratoga in the fall of 1777. But both these battles had significant irregular elements, the former being a hit-and-run strike, the latter largely the result of weeks of highly accurate sniping and harrying of British general John Burgoyne’s ill-supplied conventional columns.

After Saratoga, France entered the war on the rebel side, but this development reemphasized regular military operations as the expeditionary forces sent to America were almost all configured for conventional set-piece battles. In any event, by the time the French troops began to arrive in significant numbers, Washington had just about given up on the notion of winning a decisive pitched battle. After the hard-fought, drawn encounter at Monmouth in June 1778—in reality a near disaster—no further conventional fighting occurred in the north, where the war eventually devolved into something of a stalemate. The British held New York City but were unable to expand their control much beyond its immediate environs. The rebels held Boston and retook Philadelphia, and controlled more territory in the north overall. But they had little hope of dislodging the occupiers from New York.

It was at this moment of strategic stasis that the British sought to seize the initiative by shifting the focus of their operations to the south. Their naval capabilities made such a bold move possible, as French sea power was not concentrated in North American waters but was rather dispersed in other, ultimately illfated campaigns in the West Indies and in the Indian Ocean. So when the British struck south at the close of 1778, they were able to move without fear of interdiction. They seized Savannah, killing or capturing virtually all the rebel defending forces while suffering losses of only three killed and ten wounded.

2

Soon much of Georgia had fallen under their control. And even though a Franco-American counterattack on Savannah was mounted in 1779, British forces withstood the assault and siege, and the French expeditionary force and fleet under Admiral General Count d’Estaing soon left the Americans to their own devices—putting no small strain on the alliance. As the great American naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan observed, the French withdrawal, by “abandoning the southern states to the enemy,”

3

ceded the initiative yet again back to the British, who soon put it to good use.

In 1780 the British moved aggressively once more, seizing Charleston, South Carolina, and trapping and capturing almost the entire rebel field force there—estimates of the total vary between three thousand and five thousand. Other victories would follow, especially in irregular encounters, where the British benefited from the services of two skilled bush fighters, Major Patrick Ferguson and Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Ferguson would organize and lead Tory rangers in several successful actions—but would die in the field at King’s Mountain. Tarleton, commander of the British Legion, a mobile strike force, was a gifted cavalryman, one of whose early exploits of the war was to capture General Charles Lee while on a raid. In the southern campaign his troops won many victories against colonial irregulars and contributed heavily in conventional fights, especially at the great British victory in the Battle of Camden against Horatio Gates, the reputed hero of Saratoga—and the favored candidate of the Conway cabal to replace Washington. In the wake of the victory over Continental regulars, Tarleton was set loose to pursue and destroy rebel partisans. He soon won a resounding early victory against the guerrilla leader Thomas Sumter at Catawba Ford.